RESEARCH ARTICLE

Decolonising Citation: Indigenous Knowledge Attribution Toolkit and Australian Library Citational Practices

Kirsten Thorpe

University of Technology Sydney

Shannon Faulkhead

Museums Victoria

Lauren Booker

University of Technology Sydney

Nathan mudyi Sentance

Powerhouse Museum

Rose Barrowcliffe

Macquarie University

Abstract

This article examines the development of the Indigenous Referencing Guidance for Indigenous Knowledges within the broader context of decolonial practice in library and information studies. Academic citation practices have historically privileged Western knowledge frameworks while rendering Indigenous Knowledge systems invisible or subordinate. The Indigenous Referencing Guidance represents an intervention that seeks to address this imbalance by guiding ethical and accurate attribution of Indigenous Knowledge sources.

Developed through a partnership between the Indigenous Archives Collective and CAVAL, the Indigenous Referencing Guidance for Indigenous Knowledges project created an Indigenous Knowledge Attribution Toolkit (IKAT) that includes two key components: a decision tree providing guidance for content assessment and attribution and a comprehensive citation and referencing guide featuring examples of Indigenous attribution methods. The guidance specifically addresses academic libraries working with Indigenous information sources at the undergraduate level by acknowledging the critical need to redress power imbalances in citation processes, ensure accurate attribution, and increase the representation of Indigenous knowledges in source materials.

This paper outlines the principles underlying the development of the guide, describes the importance of using Indigenous research methodologies to guide ethical Indigenous research practices, and addresses the politics of citation. It explores the opportunities to elevate Indigenous Knowledges through citational practices by sharing examples of practical applications and use of sources described in the IKAT. By considering citations in the context of them being respectful and relational practices, the guide elevates the recognition of Indigenous Knowledges. In doing this, the IKAT specifically contributes to broader movements for Indigenous Data Sovereignty, supports the implementation of Right of Reply protocols, and advances Indigenous priorities in library and academic citation practices. The article concludes by discussing the opportunities connected with implementing the IKAT and suggests future directions for evolving citation practices that honour Indigenous Knowledges.

Keywords: Indigenous Knowledges attribution; citational justice; decolonial library practices; Indigenous cultural and intellectual property; critical information literacy; Indigenous research methodologies

How to cite this article: Thorpe, Kirsten, Shannon Faulkhead, Lauren Booker, Nathan mudyi Sentance, and Rose Barrowcliffe. 2026. Decolonising Citation: Indigenous Knowledge Attribution Toolkit and Australian Library Citational Practices. KULA: Knowledge Creation, Dissemination, and Preservation Studies 9(1). https://doi.org/10.18357/kula.315

Submitted: 31 March 2025 Accepted: 28 October 2025 Published: 19 January 2026

Copyright: © 2026 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Competing interests and funding: There are no conflicts of interests for the authors in submitting this paper.

Introduction

Citation practices allow authors to gather evidence from their research field, identify authoritative knowledge sources, and give credit and attribution to people’s ideas. However, there is growing recognition that citation practices are political, as they reinforce existing power structures by privileging which knowledge sources are legitimised, amplified, and reproduced within academic discourse. Citational justice movements recognise that traditional citation systems have systematically excluded or marginalised particular sources of knowledge, including Indigenous Knowledge sources, oral traditions, and community-based knowledges (Mott and Cockayne 2017; Ahmed 2013). Citational justice focuses attention on addressing the historical and systematic under-citation of marginalised groups in academic contexts. Further, it ensures that the intellectual contributions of all scholars are recognised and valued.

Citational justice movements have developed across different communities and contexts, each responding to particular histories of exclusion and distinct epistemologies. Among the many important citational justice initiatives that address inequities in citation are the US-based Cite Black Women movement, which highlights how centring Black women scholars’ intellectual contributions can disrupt Western white patriarchal hegemonies across academic disciplines (Smith et al. 2021); the #CiteIndigenousAuthors initiative; efforts to increase citations of scholars with disabilities; and work to amplify voices from the Global South. While their specific concerns differ, these movements share recognition that citation practices operate as mechanisms of power. Indigenous referencing guidelines and Indigenous-centred citation frameworks represent another vital thread of this citational justice work. This article’s focus on Indigenous Knowledge attribution reflects our positionality and expertise as members of the Indigenous Archives Collective working within the Australian context and acknowledges that effective citational justice work requires context-specific approaches grounded in the particular knowledge systems, cultural protocols, and historical experiences of the communities concerned.

These guidelines and frameworks challenge the structural inequities that have privileged Western written scholarship while rendering Indigenous Knowledge production invisible or delegitimised (Todd, Métis, 2016) and highlight relational accountability and respect for cultural protocols that govern how Indigenous Knowledge may be shared, cited, and utilised (Littletree, Navajo/Eastern Shoshone, Belarde-Lewis, Zuni/Tlingit, and Duarte, Xicanx/Pascua Yaqui Tribe, 2020). Over the last several years, library and information professionals have begun to confront the colonial underpinnings of information organisation and retrieval systems (Christen 2012; Littletree, Navajo/Eastern Shoshone, Belarde-Lewis, Zuni/Tlingit, and Duarte, Xicanx/Pascua Yaqui Tribe, 2020), and efforts to revise citation practices contribute to the broader movement to identify and dismantle colonial practices in library and information science and to support Indigenous worldviews and priorities in research and scholarly communication (Duarte, Xicanx/Pascua Yaqui Tribe, and Belarde-Lewis, Zuni/Tlingit, 2015; Roy, Ojibwe/Chippewa, 2015; Thorpe, Worimi, and Booker, Garigal, 2024).1 By recognising that citation practices are not neutral but powerful mechanisms that legitimise certain forms of knowledge while rendering others invisible, these movements challenge traditional Western knowledge frameworks that have historically marginalised, appropriated, and erased Indigenous Knowledge systems (Battiste, Mi’kmaw, Potlotek First Nation, 2005; Smith, Ngāti Awa, Ngāti Porou, and Tūhourangi, 2021).

The Indigenous Referencing Guidance for Indigenous Knowledges (Faulkhead, Koorie, et al. 2023) emerges from this context as a practical response to these longstanding structural inequities in citation practices. Developed through a partnership between the Indigenous Archives Collective and CAVAL,2 the report provides both a contextual framework for understanding the importance of appropriate attribution of Indigenous Knowledges and a practical tool, the Indigenous Knowledge Attribution Toolkit (IKAT). The guide’s primary purpose is to help foster critical information literacy skills among undergraduate students in Australian (specifically Victorian) academic institutions. It is intended to provide them with the context and tools to think about citation as a mechanism of power and alternative citation practices as a way to challenge the ongoing colonialism in scholarly knowledge production. However, we believe the relevance of the resource extends beyond its initial regional scope and can inform practices in educational and cultural institutions around the world. The IKAT supports changes in attribution and citation practices. Originally developed for liaison librarians and undergraduate students at Victorian universities, and since adopted more broadly, it helps readers develop the critical information literacy skills needed to question whose knowledges get valued, how information systems perpetuate colonial thinking, and how to ethically engage with and appropriately attribute Indigenous Knowledge sources.

This article is structured in four main sections. First, we outline the contextual framework that grounds this work, examining the well-documented history of extractive and exploitative research related to Indigenous peoples, which includes the appropriation, misattribution, and lack of attribution of Indigenous Knowledges; the resulting development of ethical principles and protocols for the appropriate attribution of Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP); and the appropriate citation of Indigenous Knowledges as a fundamental aspect of critical information literacy. Second, we describe the development of the guide, including the partners involved—the Indigenous Archives Collective and CAVAL—and the process of creating the IKAT. Third, we include examples of practical applications and the use of sources described in the IKAT. Finally, we conclude by discussing the opportunities connected with implementing the IKAT and suggest future directions for evolving citation practices that honour Indigenous Knowledges.

We argue that by considering citations in the context of them being respectful and relational practices, the guide not only advances Indigenous priorities in library and academic citation practices and promotes citation justice but also elevates the recognition of Indigenous Knowledges more broadly, contributing to larger-scale decolonisation and epistemic justice.

Contextual Framework

Citation practices are embedded in larger systems of knowledge production, and understanding their role in the history of extractive and exploitative research related to Indigenous peoples is essential for developing ethical alternatives. For centuries, Western researchers have extracted Indigenous Knowledge without obtaining consent or providing proper attribution (Smith, Ngāti Awa, Ngāti Porou, and Tūhourangi, 2012; Todd, Métis, 2016; Anderson and Christen 2019). Indigenous people were studied, their knowledge recorded and published, yet they were rarely cited as authors or acknowledged as intellectual authorities. Instead, citations flowed to non-Indigenous researchers who built careers on Indigenous Knowledge while Indigenous peoples remained invisible in bibliographies and reference lists. This systematic erasure operates through attribution. Citation functions as a key mechanism that maintains hierarchies of knowledge production by reducing Indigenous subjectivity and legitimating the ongoing appropriation of Indigenous cultural material by non-Indigenous authors (Anderson and Christen 2019).

The history of research about Indigenous peoples and Indigenous Knowledges is one of extraction and exploitation. For Indigenous people, research has been used as a “critical tool of colonization” (Archibald, Sto:lo First Nation, Morgan, Waikato, Ngati Mahuta, and Te Ahiwaru, and De Santolo, Garrwa and Barunggam, 2019, 5), producing shared experiences of “unrelenting research of a profoundly exploitative nature” (Smith, Ngāti Awa, Ngāti Porou, and Tūhourangi, 2012, 59). As Linda Tuhiwai Smith (Ngāti Awa, Ngāti Porou, and Tūhourangi) states, “it appals us that the West can desire, extract and claim ownership of our ways of knowing, our imagery, the things we create and produce, and then simultaneously reject the people who created and developed those ideas and seek to deny them further opportunities to be creators of their own culture and own nations” (2012, 19–20). The dispossession of Indigenous lands runs hand in hand with the dispossession of knowledge, as taking land requires knowledge about the land (Anderson and Christen 2019). Conferring authorship to non-Indigenous collectors and document producers becomes a complementary modality of settler ownership of both lands and the knowledge systems connected to those territories. The attribution and citation of Indigenous Knowledges in research and institutional collections is thus inherently political (Thorpe, Worimi, Galassi, and Franks 2016; Lovett, Wongaibon/Ngiyampaa, et al. 2020).

In 2020, the Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) released the AIATSIS Code of Ethics for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Research (the AIATSIS Code). The AIATSIS Code sets out ethical standards for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander research, including activities relating to research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander collections. Four main principles inform the framework: Indigenous self-determination; Indigenous leadership, impact and value; sustainability; and accountability (AIATSIS 2020, 9). These principles directly inform the citation and attribution practices advocated for in the IKAT, which provides ethical guidelines for acknowledging Indigenous Knowledges in academic contexts.

The AIATSIS Code’s principles set a pathway for respectful engagement in Indigenous research and respond to histories of colonisation and exploitative research practices. For Indigenous peoples, the ongoing experiences of colonisation, theft of lands and resources, disruption to societies and families, and suppression of culture and identity are a denial of human dignity and respect. When done well, research can have, and has had, positive impacts for Indigenous peoples, but research has not been immune to practices that are imbued with racism, exploitation, and disrespect (AIATSIS 2020, 11). The Code seeks to counter these harmful practices. The development of Indigenous-centred citation frameworks, as embodied in the IKAT, provides a practical application of these principles, addressing historical power imbalances in academic attribution to recognise and value Indigenous Knowledge systems alongside Western academic traditions.

In an Australian context, a number of protocols have been developed to guide library and information work to respect Indigenous Knowledges and intellectual property. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Library and Information Resources Network’s (ATSILIRN) Protocols for Libraries, Archives and Information Services (2012) and the University of Sydney’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cultural Protocols (Sentance, Wiradjuri, and University of Sydney Library 2021) are examples of these protocols. In addition, the True Tracks principles developed by Terri Janke (Wuthathi/Meriam) offer support for Indigenous peoples’ control of their cultural heritage with the concept of ICIP rights. Janke’s work builds on her landmark 1998 report, Our Culture: Our Future, which was the first to document the issues with ICIP in Australia comprehensively. Reflecting on this earlier work, Janke (Wuthathi/Meriam, 2021, 11) explains that Our Culture: Our Future “was the first time a report had set out the issues with ICIP in Australia, and their effects on Indigenous Australians—what they felt was being exploited, how it made them feel, and what rights they needed to prevent appropriation and allow them to control the dynamic of their own cultures.” The report analysed existing copyright, intellectual property, and heritage laws, finding them inadequate to protect Indigenous cultural knowledge, and called for comprehensive changes to laws, practices, and policies to support Indigenous empowerment.

Ten principles underpin the True Tracks model, and all are viewed as being interrelated and embedded in meaningful relationships and connections (Janke, Wuthathi/Meriam, 2021, 15). They include respect, self-determination, consent and consultation, interpretation, integrity, secrecy and privacy, attribution, benefit sharing, maintaining Indigenous Cultures, and recognition and protection. Under the principle of attribution, Janke (Wuthathi/Meriam, 2021, 25) emphasises that acknowledging Indigenous people as custodians of Indigenous cultural knowledge is an aspect of respect and integrity, particularly because Indigenous cultural material has often been exploited without respect, benefit, or recognition of its origin from a distinct cultural group. Janke (Wuthathi/Meriam, 2021, 25) states: “Where possible, the source of Indigenous music, songs and traditional knowledge should be noted by stating the name of the performer, if applicable, and the relevant Indigenous group or community. In this way, the music and knowledge can be traced back to the person, family or clan.” Critically, Janke (Wuthathi/Meriam, 2021, 25) observes that copyright law prioritises individual artists over the clan groups who are the source communities, demonstrating why attribution practices must recognise both individual knowledge holders and the collective cultural systems from which their knowledge originates. These principles provide the ethical foundation for the practical citation guidance developed in the IKAT, which translates these protocols into concrete practices for undergraduate students and librarians.

Critical Information Literacy Skills and the Attribution of Indigenous Knowledges

Critical information literacy is evident in various library and information practices, including collection development decisions, cataloguing and classification systems, metadata creation, access policies, and citation practices. Given the history of extractive research practices and the systematic misattribution of Indigenous Knowledge discussed above, developing critical information literacy is essential to interrupt these patterns. Each of these areas involves choices about which knowledge systems are legitimised, how information is organised and made discoverable, and whose voices are centred or marginalised. According to Eamon Tewell, “critical information literacy (CIL) seeks to understand and act upon how libraries and other information systems both contribute to and can oppose systemic oppression such as racism, sexism, and ableism” (2025, 483). This framework recognises that information practices—including the citation practices that rendered Indigenous peoples invisible as authors and knowledge holders while elevating non-Indigenous researchers—are never neutral but rather reflect and perpetuate existing power structures.

Libraries are uniquely positioned to promote and address citational justice for Indigenous Knowledges. Already responsible for teaching citation practices to undergraduate students, libraries can ensure their pedagogical guidance reflects decolonial principles rather than perpetuating colonial hierarchies. Their cross-disciplinary reach allows them to implement ethical frameworks that complement discipline-specific initiatives, and their citation guidance connects to broader decolonial work in libraries on cataloguing, metadata, and access policies, creating a broader approach to recognise Indigenous Knowledges. These practices are interconnected sites of power where critical information literacy can challenge colonial knowledge systems. In collection development, critical approaches question which materials are acquired and preserved; in cataloguing and classification, they challenge subject headings and knowledge organisational practices that marginalise or misrepresent Indigenous peoples; in metadata creation, they ensure proper attribution and cultural context; and in access policies, they recognise Indigenous protocols for knowledge sharing.

While critical information literacy encompasses these domains, citation practices stand out as a vital area for intervention because they directly reflect and reproduce knowledge hierarchies within academic discourse. The act of citation—deciding which sources are considered authoritative, how knowledge holders are acknowledged, and whose intellectual contributions are made visible—is fundamental to how students and researchers engage with and validate knowledge systems. This makes citation an important starting point for developing critical information literacy skills, as it requires students to actively question whose knowledge is valued, reflect on their own beliefs and assumptions about authority, and practice more respectful forms of knowledge attribution.

Citational justice extends beyond increasing citations to marginalised scholars—it also involves critical decisions about who not to cite and how to engage ethically with problematic sources. In the context of Indigenous Knowledge systems, this includes recognising cultural protocols that govern knowledge sharing and restrict certain knowledge from public circulation (Christen 2012). We recognise that Indigenous communities hold the authority to determine which knowledges can be shared in specific contexts, and that these decisions are governed by cultural protocols specific to each Nation and community. The IKAT does not guide these approaches, as this authority rests with Indigenous Knowledge holders. Instead, the toolkit focuses on whether existing published sources demonstrate informed consent and ethical research practices.

Additionally, the process of determining what not to cite involves evaluating older sources that may contain Indigenous cultural information obtained without informed consent or protection of ICIP rights. Many legacy publications reflect the extractive research practices discussed above, and citing such sources without acknowledging their problematic provenance can perpetuate harm. The IKAT addresses this complexity by guiding students to determine whether a source is appropriate to cite at all, considering factors such as whether informed consent was obtained, whether the source discusses its ethical research practices, and whether Indigenous Knowledge holders are appropriately attributed.

As the Indigenous Referencing Guidance for Indigenous Knowledges states,

Critical information literacy requires researchers to understand the social and political context of information creation and how power shapes how information is created, made accessible and used. It requires that librarians and students engage in dialogue [with Indigenous Knowledge holders and communities] to understand the inherently political and complex nature of information production and to understand the systems of oppression that exist within information production and the opportunities to take action to address and dismantle them (Tewell 2015, 24; Tewell 2016; Smith, Ngāti Awa, Ngāti Porou, and Tūhourangi, 2021). In practice, students seek to reject notions of information neutrality and understand power dynamics and effect change by questioning dominant forms of information transmission. Scholarship also points to issues of structural racism and race (Rapchak 2019, 174) and the need to understand the past to decolonise libraries and librarianship (Edwards, Red River Métis, 2019). (Faulkhead, Koorie, et al. 2023, 3)

Critical information literacy approaches gain further depth when students recognise Indigenous peoples’ rights to attribution and representation. Anderson and Christen (2019) argue that attribution has historically functioned as a form of property and a colonial practice of exclusion, suggesting that properly acknowledging Indigenous contributions is a necessary counterbalance. This perspective builds upon previous work examining intellectual property and moral rights within library and archival contexts (Janke, Wuthathi/Meriam, 2021; Janke, Wuthathi/Meriam, and Iacovino 2012; Anderson 2005; Nakata, Torres Strait Islander, et al., 2005).

By developing specialised citation guides and resources, librarians can support students in identifying and addressing attribution gaps, critically evaluating what constitutes an authoritative source, and implementing respectful citation practices that honour Indigenous Knowledge holders and provide appropriate attribution of Indigenous Knowledge sources. This practical guidance is also a tool for ethical scholarship and a foundation for deeper conversations about knowledge production, validation, power dynamics, and the ongoing work of decolonising academic spaces. These resources help to transform institutional practices, challenge the colonial legacies embedded in traditional academic citation practices, and contribute to citational justice.

Developing the Indigenous Referencing Guidance for Indigenous Knowledges

Collaborative Methodology: The Indigenous Archives Collective

The Indigenous Archives Collective (the Collective) emerged from a recognised need to connect professionals working with Indigenous Knowledge materials across galleries, libraries, archives, and museums (GLAM). Conversations among practitioners in Australia, the United States, and Aotearoa/New Zealand highlighted a common challenge: Many Indigenous library and archive workers were operating in isolation, each independently navigating complex questions about the ethical care of, management of, and access to Indigenous cultural materials. This shared experience of navigating similar challenges across different institutional contexts shaped the Collective’s collaborative and consultative approach to the project. The Collective was initially established in 2011 as the Indigenous Archives Network through a National Archives of Australia Ian Maclean Research Award, and it was revitalised in 2018 under its current name to foster collaborative approaches to Indigenous-led priorities in the GLAM sector.

The Indigenous Archives Collective operates as a collaborative network of Indigenous and non-Indigenous academics and professionals committed to advancing priorities for Indigenous people across the GLAM sector. The Collective’s operational principles directly informed the Indigenous Referencing Guidance project methodology. The Collective functions as a space for nourishment and support, culturally safe collaboration that centres Indigenous self-determination, dialogue and reflexive practice, and advocacy for transformative changes in the sector. These principles guided how the research team approached the development of the referencing guidance. While the Collective’s membership extends internationally, the Indigenous Referencing Guidance project team comprised Australian-based members developing guidance specifically for the Australian (particularly Victorian) context, which determined the methodological emphasis on Australian frameworks such as the AIATSIS Code.

The work of the Collective is also guided by broader Australian guidelines for ethical practice in research. This ethical framework underpinned the project’s methodology. These ethical practices are guided fundamentally by the rights articulated in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which include the right to self-determination and free, prior and informed consent and are fundamental human rights for Indigenous peoples internationally (UNDRIP 2007). These rights extend to the maintenance, control, use, and attribution of ICIP (Janke, Wuthathi/Meriam, 2019).

Project Context and Need

The Indigenous Referencing Guidance for Indigenous Knowledges (Faulkhead, Koorie, et al. 2023) responds to the critical need for rebalancing power relationships in citation processes in Indigenous contexts in Australia. Commissioned by CAVAL for use across Victorian academic institutions, the project developed practical guidance to support undergraduate students and their liaison librarians when citing Indigenous Knowledge sources in academic writing. The resulting Indigenous Knowledge Attribution Toolkit, the IKAT, provides both a decision-making framework for evaluating the appropriateness of sources and specific citation examples that centre on Indigenous authority and cultural protocols. The IKAT aims to enhance accurate attribution and increase the representation of Indigenous Knowledges in scholarly works by thoughtfully examining the intersections between conventional library practices and Indigenous ways of knowing, being, and doing. CAVAL commissioned this work through academic libraries, recognising their capacity to integrate ethical citation guidance systematically across disciplines through liaison librarians who regularly provide referencing support to students.

When the project was initiated, “CAVAL ha[d] [already] conducted an extensive environmental scan, reviewing key policies and literature relating to Indigenous knowledges, attribution and citation” (Faulkhead, Koorie, et al. 2023, 5). Based on that scan, CAVAL concluded that although “multiple citation styles, attribution labels and style guides ha[d] been developed to centre Indigenous peoples as the creators and authoritative voices of their own knowledges in Australia (Sentance [Wiradjuri,] 2020; Hromek [Budawang/Dhurga/Yuin and Burrier/Dharawal] and Herbert, 2016) and internationally (Local Contexts, n.d.; Younging [Opaskwayak Cree Nation,] 2018; Macleod 2021) . . . there ha[d] been a lack of comprehensive application and support of these citation styles across academic teaching” and library services in Australia (Faulkhead, Koorie, et al. 2023, 5). The scan identified that James Cook University had developed referencing guidance titled “Using Works of First Nations People” for the seventh edition of the American Psychological Association (APA) style guide in 2021 (James Cook University n.d.), but such examples were not widespread.

CAVAL funded this research after the Indigenous Archives Collective responded to a call for expressions of interest (EOI) for the “CAVAL Consultation Partner – Referencing guidance for Indigenous Knowledges” in June 2022. Following the Collective’s successful application, Collective members Dr. Shannon Faulkhead, Dr. Kirsten Thorpe, Dr. Lauren Booker, Dr. Rose Barrowcliffe, and Nathan Sentance formed the research team. The project was administered through the University of Technology Sydney’s Jumbunna Institute for Indigenous Education & Research, and the team met with CAVAL’s Acknowledging Cultural Authority and Indigenous Knowledges in Referencing Working Group (CACIK) to discuss project scope and aims. The research methods included seeking guidance from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community members and organisations, such as the Yoowinna Wurnalung Aboriginal Healing Service, Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Advisory Committee at Museums Victoria, and members of the Indigenous Archives Collective. While initially designed for CAVAL libraries to support acknowledgment of First Nations peoples in Victoria, the toolkit has been adopted by institutions beyond Victoria and has clear applications for Indigenous Knowledge attribution across Australia when adapted through appropriate consultation with local Indigenous communities.

The Indigenous Knowledges Attribution Toolkit (IKAT)

The Indigenous Knowledge Attribution Toolkit (IKAT) guides students and researchers to critically examine knowledge politics and their responsibilities as knowledge users through the following practical resources: a decision tree guiding users through content assessment and appropriate attribution methods; a detailed citation and referencing guide with specific examples that incorporate Indigenous attribution principles; and templates and frameworks that accommodate diverse knowledge sources, including oral traditions, community knowledge, and cultural expressions. By providing these structured yet flexible tools, the IKAT empowers students to engage ethically with Indigenous Knowledge while respecting cultural protocols and ownership. This represents a significant step toward decolonising citation practices and creating more inclusive knowledge systems within academic environments.

The IKAT was developed to address critical gaps in how students engage with Indigenous Knowledges. Specifically, it aims to help students critically analyse sources, respect Indigenous Knowledge authority, support the reclamation of Indigenous Knowledges, understand one’s own positionality in relation to Indigenous Knowledges, and confidently draw on and appropriately attribute Indigenous Knowledges (Faulkhead, Koorie, et al. 2023). By engaging with the IKAT, students and researchers are encouraged to reflexively consider their responsibilities and obligations in conducting ethical and relevant research that recognises Indigenous people’s research priorities.

APA style was chosen for the Indigenous Referencing Guidance project because it is the primary citation format used in social sciences, education, and library and information science at CAVAL member institutions. This makes it the most relevant format for the undergraduate students and liaison librarians that the guide is intended to support. However, while the recommendations for the citation format align with the APA style, this toolkit aims to build a more critical and robust research process when considering attribution, using, and citing resources related to Indigenous Knowledges.

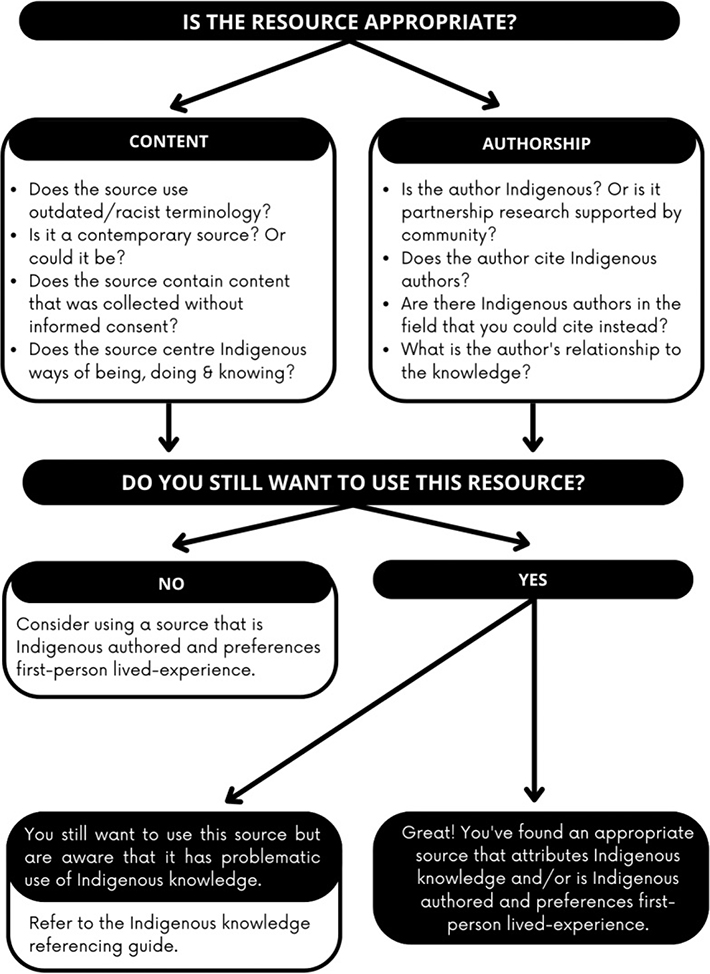

Recognising that undergraduate students may not yet have developed the critical frameworks to discern between appropriate and problematic sources, the IKAT provides a structured workflow in a decision tree (Figure 1) to guide them and their supporting librarians through this evaluation process. The toolkit acknowledges that determining a source’s appropriateness must precede decisions about attribution methods; therefore, users are directed to consult the decision tree first before applying the citation guide to ethically acknowledge Indigenous Knowledge sources.3

Figure 1. The IKAT decision tree (Faulkhead, Koorie, et al. 2023).

As part of the workflow, the IKAT begins with the critical question: Is the source appropriate for the research topic? This question and subsequent questions prompt students to critically evaluate whether the source represents the most appropriate knowledge for their research topic. Every academic discipline includes Indigenous scholars and/or research publications that respectfully incorporate Indigenous ways of knowing, being, and doing. The toolkit encourages students to prioritise these sources whenever possible. The IKAT decision tree presents a series of guiding questions to help determine source appropriateness, with the following detailed guidance provided to support this critical evaluation process. Key guiding questions in relation to content include:

- Does the resource use outdated or racist terminology?

- Is it a contemporary source? Or could it be?

- Does the source contain content that was collected without informed consent?

- Does the source centre Indigenous ways of being, doing, and knowing?

The IKAT instructs users to critically assess citation sources by prioritising contemporary research incorporating Indigenous methodologies over legacy publications with outdated worldviews. It directs readers to assess sources in regard to ethical research practices—for example, by assessing evidence of free, prior, and informed consent from Indigenous participants or collaboration such as Indigenous co-authorship. The guidance discusses the importance of citing Indigenous sources, including oral testimony and grey literature, directly whenever possible. For cases where Indigenous oral histories appear in non-Indigenous publications, the toolkit provides specific citation approaches that respect both copyright and Indigenous Knowledge ownership.

In addition to considering the appropriateness of the content, the IKAT encourages students to consider the authorship of the publication, asking specifically “What is the author’s relationship to the knowledge?” It calls for people to understand that Indigenous Knowledge has protocols and responsibilities attached to it and any publication of Indigenous Knowledge should adhere to them. Guiding questions in relation to authorship include:

- Is the author Indigenous? Or is it partnership research supported by community?

- Does the author cite Indigenous authors?

- Are there Indigenous authors in the field that you could cite instead?

- What is the author’s relationship to the knowledge?

The guidance advises students to identify Indigenous authors through their stated positionality, including community, Nation, and Language Group affiliations typically found in author biographies or publication introductions. It highlights the importance of prioritising Indigenous-authored sources when discussing Indigenous people, culture, knowledge, and lived experiences, noting that most academic disciplines include Indigenous researchers whose work should be cited. Recognising the diversity of Indigenous cultures and identities, the toolkit instructs users to seek sources with the closest relationship to the specific knowledge being discussed, recommending that research about particular Country (such as Woi Wurrung) should preferentially cite knowledge holders from that specific cultural group rather than applying a homogeneous approach to Indigenous Knowledge citation.

Guidance for Citing and Referencing Indigenous Knowledges

Once a source is deemed relevant and appropriate, students need to properly attribute the Indigenous Knowledge it contains. This attribution might recognise either the Indigenous author of the publication being cited or the Indigenous Knowledge holder referenced within a non-Indigenous-authored work. The toolkit acknowledges that, in some instances, students might need to use problematic resources when they remain the most appropriate or only available sources. The IKAT citation guide provides specific examples and strategies for ethically attributing Indigenous Knowledge from diverse source types while acknowledging their limitations.

The IKAT recommends including reference to Indigenous authors’ Nation, Country, or Language Group affiliation in both in-text citations and reference lists. This practice centres Indigenous identity and connection to Country, making visible the specific cultural context from which the author speaks. This attribution recognises that Indigenous Knowledge is place-based and reflects the particular relationships and responsibilities authors hold to their communities and lands.

The primary focus of the IKAT is to support the attribution of Indigenous Knowledge and Indigenous-authored sources. In doing so, it reflects the project’s aim to address the historical erasure and misattribution of Indigenous Knowledge holders in academic citation. The toolkit does not provide guidance on marking non-Indigenous authorship, recognising that decisions about whether to make all authorial positionality visible (including marking non-Indigenous or settler identity) involve broader considerations of citational justice beyond the scope of this project. When an Indigenous author has not included a reference to their Nation, Country, or Language Group affiliation in the referenced publication, the IKAT recommends citing them without this information. This approach respects the author’s choice about how they wish to be identified in academic contexts. Students and researchers should include only cultural affiliations that authors have publicly made available in their published works or author biographies.

The IKAT citation guide provides a comprehensive framework for attributing Indigenous Knowledge across multiple source types and authorship contexts. It systematically addresses three key citation scenarios: works directly authored or co-authored by Indigenous creators (with specific guidance for books, book chapters, social media, multimedia content, websites, blogs, journal articles, and personal communications); Indigenous Knowledge cited within Indigenous-authored publications (covering books, newspaper articles, and journal articles); and Indigenous Knowledge appearing in non-Indigenous-authored works (addressing books, journal articles, and newspaper articles). This structured approach enables students to correctly attribute Indigenous Knowledge regardless of the publication format while consistently recognising the original knowledge holders and their cultural connections.

Examples

Book

In-Text Format

(Surname, Nation/Country/Language Group, year) or Surname (Nation/Country/Language Group) (year)

Examples

(Moreton-Robinson, Goenpul, 2020)

As argued by Moreton-Robinson (Goenpul) (2020) . . .

Reference List Format

Author Surname, Initials. (Nation/Country/Language Group). (Year). Book Title. Publisher.

Examples

Moreton-Robinson, A. (Goenpul). (2020). Talkin’ Up to the White Woman. University of Queensland Press.

Book Chapter

In-Text Format

(Surname, Nation/Country/Language Group, year) or Surname (Nation/Country/Language Group) (year)

Examples

(De Santolo, Garrwa; Barunggum, 2019)

As argued by De Santolo (Garrwa; Barunggum) (2019) . . .

Reference List Format

Author Surname, Initials. (Nation/Country/Language Group). (Year). Title of chapter. In Editor(s) initial(s) and surname. (Nation/Country/Language Group). (Ed. OR Eds.), Title of book, (page numbers). Publisher.

Examples

De Santolo, J. (Garrwa; Barunggum). (2019). The emergence of Yarnbar

*Tip: An author/s or editor/s Nation, Country or Language group may be published in a contributor section of the book rather than in the individual chapter.

Jarnngkurr from Indigenous homelands: a creative Indigenous methodology. In J. Archibald (Stó:lō; St’at’imc), J. Lee-Morgan (Waikato-Tainui; Ngāti Mahuta) & J. De Santolo. (Garrwa; Barunggum). (Eds.), Decolonizing research: Indigenous storywork as methodology (pp. 239-259). ZED Books LTD.

Website

In-Text Format

(Surname, Nation/Country/Language Group, year) or Surname (Nation/Country/Language Group), (year)

Examples

(Cromb, Gamilaraay, 2022)

As argued by Cromb (Gamilaraay), (2022) . . .

Reference List Format

Author name, Initials. (Nation/Country/Language Group). (Year, Month Day-if available). Title of page-website name. URL

Examples

Cromb, N. (Gamilaraay). (2022). So whose ‘Voice’ is it anyway?-Nat Cromb-IndigenousX. https://indigenousx.com.au/so-whose-voice-is-it-anyway/

While the current IKAT examples focus on published sources, guidance for citing oral traditions and cultural expressions will be developed for inclusion in the 2026 update, recognising these knowledge forms as equally authoritative sources that require appropriate attribution frameworks.

Enacting a Right of Reply Through the IKAT

Importantly, the toolkit draws attention to the lack of correct attribution in historical sources due to misinformation, poor recordkeeping, purposeful destruction, and the privileging of the collector and Western perspectives. In essence, it addresses the critical need for a Right of Reply to be enacted to acknowledge Indigenous people’s contributions (Indigenous Archives Collective 2021). The Right of Reply refers to Indigenous peoples’ authority to respond to, correct, and contextualise existing records and representations about themselves, their cultures, and their knowledges. In the context of citation practices, the Right of Reply is enacted when students and researchers properly attribute Indigenous Knowledge to its rightful owners—even in historical sources where original attribution was absent, incorrect, or credited only to non-Indigenous collectors and authors. By using the IKAT citation methods to attribute knowledge to specific Indigenous Nations, communities, or knowledge holders rather than solely to the non-Indigenous authors who published it, researchers enable a form of corrective attribution that restores visibility to Indigenous Knowledge authority. This practice actively challenges the colonial erasure embedded in legacy publications and repositions Indigenous peoples as the intellectual authorities of their own knowledges.

The IKAT provides a specific example of this practice. When citing a historical ethnographic text where Narrangga knowledge was recorded by non-Indigenous researchers, the IKAT guides students to cite it as “Narrangga in Nunn and Reid (2015),” foregrounding the Narrangga people as the knowledge holders while acknowledging the publication source (Faulkhead, Koorie, et al. 2023).

Outside of an academic context, there is a growing awareness in collecting institutions such as galleries, libraries, archives, and museums regarding the issues of minimal or unknown provenance for ICIP in exhibition labelling and catalogue metadata. For example, the Australian Museum uses the attribution “made by Ancestor/s” in exhibition labelling where the creator was not recorded (Sentance, Wiradjuri, 2018). This guide draws on work undertaken in collecting institutions to attribute Indigenous Knowledge ownership when there is little or no provenance for that knowledge.

Future Directions

The IKAT was developed as a living document that is dynamic and open to discussion and amendment. The toolkit is a starting point for conversation and guidance for Indigenous attribution within academic referencing practices while acknowledging that the document requires ongoing feedback from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, particularly Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people based in Victoria. This project’s scope was to develop guidance for undergraduate students and liaison librarians supporting these students. Further work is needed to develop support for higher degree research (HDR) students and research staff to consider informed consent and build attribution into the entire research cycle, including the ethics process. This resource does not address these areas and considers them spaces for future research.

Since its launch in 2023, the IKAT has been made available to broad networks under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license. This license permits adaptation and distribution for non-commercial purposes provided that appropriate attribution is given. CAVAL continues to encourage liaison librarians to incorporate the guidance into their work with undergraduate student cohorts. The toolkit is designed to be a living document, reflecting the understanding that citation practices and community needs are continually evolving. A year-end event in 2023 offered users the opportunity to share feedback and experiences, which will inform ongoing improvements to the resource. The toolkit’s three-year review cycle, with the first significant update scheduled for 2026, ensures that it remains responsive to user experiences, community feedback, and evolving best practices in the attribution of Indigenous Knowledges. This review will include developing citation guidance for oral traditions and cultural expressions, expanding beyond the current focus on published sources to recognise diverse forms of Indigenous Knowledge transmission.

The limitations of the IKAT must be addressed in future updates. For example, the tool’s adaptation to broader regional and cultural contexts requires consideration. While the intention of the tool is to support diversity, it is worth questioning whether universal tools are genuinely feasible or desirable. This paper has explored the relationship between IKAT and citational justice, but it is essential to consider whether the tool alone is sufficient to achieve these objectives. The IKAT assumes that we have easy access to the work of Indigenous scholars and can readily identify appropriate and authoritative sources; however, this is not always the case.

Building on these foundations, future developments of the IKAT should explicitly connect citation practices to broader Indigenous Data Sovereignty frameworks, including the CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance developed by the Global Indigenous Data Alliance (GIDA) (Global Indigenous Data Alliance n.d; Maiam nayri Wingara 2018; Walter, Palawa, et al. 2021; Prehn, Worimi, et al. 2024). The CARE Principles—Collective Benefit, Authority to Control, Responsibility, and Ethics—provide a framework for ensuring that data practices, including citation, support Indigenous peoples’ rights and interests. This includes creating pathways for citation practices that acknowledge collective ownership and support Indigenous governance of data. This approach ensures citation practices are integrated early in the research lifecycle, establishing mechanisms that recognise all rights and incorporate appropriate attribution for research outputs, including datasets, publications, and derivative materials.

Conclusion

The development of the IKAT contributes to addressing the power imbalances embedded in academic citation practices. By providing practical guidance for ethical attribution of Indigenous Knowledge sources, the IKAT confronts the historical privileging of Western knowledge frameworks that have long rendered Indigenous ways of knowing invisible or subordinate within scholarly discourse.

Our work challenges the notion that citation is a neutral practice. Instead, we position it as inherently political—a mechanism that either reinforces or disrupts existing knowledge hierarchies. The IKAT decision tree and accompanying citation guide offer concrete pathways for students and librarians to critically evaluate sources, prioritise Indigenous-authored materials, and properly attribute knowledge ownership across diverse formats. In doing this, the IKAT enables the recognition of Indigenous self-determination as articulated in the AIATSIS Code of Ethics.

The Indigenous Referencing Guidance for Indigenous Knowledges project creates a space for Indigenous reclamation and resistance. When students develop critical information literacy skills, they engage with citation as a process to redress power and to dismantle the colonial foundations of academic knowledge production. While our immediate focus has been supporting undergraduate students in Victorian academic libraries, the principles underpinning the IKAT have broader applications across educational and cultural institutions. Further work is needed to extend these guidelines to HDR contexts, embed attribution considerations throughout the research ethics process, and continue refining the toolkit through ongoing dialogue with Indigenous communities. As a living document, the IKAT remains open to amendment and evolution through feedback from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge holders.

This work demonstrates how academic libraries can contribute meaningfully to structural changes to honour and respect Indigenous Knowledges. Future work in this area requires a continued commitment to Indigenous-led priorities, critical reflection on institutional practices, and recognition of citation as a relational practice grounded in respect and reciprocity. Appropriate citation of Indigenous Knowledge in academic contexts demands a deliberate focus on and active support for Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Indigenous Data Governance principles throughout the research lifecycle, including within citation practices.

Acknowledgements

The authors of this paper acknowledge the Traditional Owners on whose Country this paper and the Indigenous Referencing Guidance for Indigenous Knowledges was written. We acknowledge their continuing knowledge authority and pay our respects to Elders, and leaders, past and present.

This article draws on and includes parts of the authors’ production of the Indigenous Referencing Guidance for Indigenous Knowledges publication (licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA) produced for CAVAL (Faulkhead, Koorie, et al. 2023). This project was funded by CAVAL through an EOI process.

References

AIATSIS. 2020. AIATSIS Code of Ethics for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Research. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. https://aiatsis.gov.au/research/ethical-research/code-ethics.

Ahmed, Sara. 2013. “Making Feminist Points.” Feminist Killjoys (blog). September 11, 2013. https://feministkilljoys.com/2013/09/11/making-feminist-points/.

Anderson, Jane. 2005. “Access and Control of Indigenous Knowledge in Libraries and Archives: Ownership and Future Use.” American Library Association and The MacArthur Foundation. https://ccnmtl.columbia.edu/projects/alaconf2005/paper_anderson.pdf.

Anderson, Jane, and Kimberly Christen. 2019. “Decolonizing Attribution: Traditions of Exclusion.” Journal of Radical Librarianship 5: 113–52. https://journal.radicallibrarianship.org/index.php/journal/article/view/38.

Archibald, Jo-ann (Sto:lo First Nation), Jenny Morgan (Waikato, Ngati Mahuta, and Te Ahiwaru), and Jason De Santolo, (Garrwa and Barunggam). 2019. Decolonizing Research: Indigenous Storywork as Methodology. ZED Books.

ATSILIRN. 2012. ATSILIRN Protocols for Libraries, Archives and Information Services. 2nd ed. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Library, Information and Resource Network. https://atsilirn.aiatsis.gov.au/protocols.php.

Battiste, Marie. (Mi’kmaw, Potlotek First Nation). 2005. “Indigenous Knowledge: Foundations for First Nations.” WINHEC: International Journal of Indigenous Education Scholarship 1 (1): 1–17. https://journals.uvic.ca/index.php/winhec/article/view/19251.

Christen, Kimberley A. 2012. “Does Information Really Want to Be Free? Indigenous Knowledge Systems and the Question of Openness.” International Journal of Communication 6: 2870–93. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/1618.

Duarte, Marisa Elena (Xicanx/Pascua Yaqui Tribe), and Miranda Belarde-Lewis (Zuni/Tlingit). 2015. “Imagining: Creating Spaces for Indigenous Ontologies.” Cataloging & Classification Quarterly 53 (5–6): 677–702. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639374.2015.1018396.

Edwards, Ashley (Red River Métis). 2019. “Unsettling the Future by Uncovering the Past: Decolonizing Academic Libraries and Librarianship.” Partnership: The Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research 14 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v14i1.5161.

Faulkhead, Shannon (Koorie), Kirsten Thorpe (Worimi), Lauren Booker (Garigal), Rose Barrowcliffe (Butchulla), and Nathan Sentance (Wiradjuri). 2023. Indigenous Referencing Guidance for Indigenous Knowledges. CAVAL and Jumbunna Institute for Indigenous Education and Research. https://www.caval.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/CAVAL_Indigenous_Knowledges_Citation_Guide.pdf.

Global Indigenous Data Alliance. n.d. “CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance.” Accessed October 15, 2025. https://www.gida-global.org/care.

Hromek, Danièle (Budawang/Dhurga/Yuin and Burrier/Dharawal), and Sophie Herbert. 2016. Indigenous Materials Referencing Guide: APA and Harvard. University of Technology Sydney Library. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/201331/.

Indigenous Archives Collective. 2021. “The Indigenous Archives Collective Position Statement on the Right of Reply to Indigenous Knowledges and Information Held in Archives.” https://indigenousarchives.net/indigenous-archives-collective-position-statement-on-the-right-of-reply-to-indigenous-knowledges-and-information-held-in-archives/.

James Cook University Library. n.d. “APA (7th Edition) Referencing Guide: First Nations Works.” Accessed February 15, 2023. https://libguides.jcu.edu.au/apa/First-Nations.

Janke, Terri (Wuthathi/Meriam). 2019. “True Tracks: Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property Principles for Putting Self-determination into Practice.” PhD diss., Australian National University. https://doi.org/10.25911/5d51497c97823.

Janke, Terri (Wuthathi/Meriam). 2021. True Tracks: Respecting Indigenous Knowledge and Culture. UNSW Press.

Janke, Terri (Wuthathi/Meriam), and Livia Iacovino. 2012. “Keeping Cultures Alive: Archives and Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property Rights.” Archival Science 12 (2): 151–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-011-9163-0.

Justice, Daniel Heath (Cherokee Nation). 2018. Why Indigenous Literatures Matter. Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Littletree, Sandra (Navajo/Eastern Shoshone), Miranda Belarde-Lewis (Zuni/Tlingit), and Marisa Duarte (Xicanx/Pascua Yaqui Tribe). 2020. “Centering Relationality: A Conceptual Model to Advance Indigenous Knowledge Organization Practices.” Knowledge Organization 47 (5): 410–26. https://doi.org/10.5771/0943-7444-2020-5-410.

Local Contexts. n.d. “Traditional Knowledge and Biocultural Labels and Notices.” Accessed January 20, 2023. https://localcontexts.org/labels-and-notices/traditional-knowledge-labels/.

Lovett, Raymond (Wongaibon/Ngiyampaa), Vanessa Lee (Yupungathi and Meriam), Tahu Kukutai (Ngāti Ti−pā, Ngāi Mahanga, Ngāti Kinohaku, Ngāti Ngawaero and Te Aupo−uri), Donna Cormack (Kai Tahu, Kāti Māmoe), Stephanie Carroll Rainie (Ahtna Athabascan), and Jennifer Walker (Haudenosaunee member of Six Nations of the Grand River). 2020. “Good Data Practices for Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Governance.” In Good Data, edited by Angela Daly, S. Kate Devitt, and Monique Mann. Institute of Network Cultures.

MacLeod, Lorisia. 2021. “More Than Personal Communication: Templates For Citing Indigenous Elders and Knowledge Keepers.” KULA: Knowledge Creation, Dissemination, and Preservation Studies 5 (1). https://doi.org/10.18357/kula.135.

Maiam nayri Wingara. 2018. “Maiam nayri Wingara Indigenous Data Sovereignty Principles.” https://www.maiamnayriwingara.org/mnw-principles.

Mott, Carrie, and Daniel Cockayne. 2017. “Citation Matters: Mobilizing the Politics of Citation Toward a Practice of ‘Conscientious Engagement.’” Gender, Place & Culture 24 (7): 954–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2017.1339022.

Nakata, Martin (Torres Strait Islander), Vicky Nakata, Alex Byrne, and Gabrielle Gardiner. 2005. “Indigenous Knowledge, the Library and Information Service Sector, and Protocols.” Australian Academic & Research Libraries 36 (2): 7–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2005.10721244

Prehn, Jacob (Worimi), Cassandra Sedran-Price (Muruwari/Gangugari), Gawaian Bodkin-Andrews (D’harawal), Maggie Walter (Palawa), and Ray Lovett (Wongaibon/Ngiyampaa). 2024. “Social Research and Indigenous Data Sovereignty.” In The Sage Handbook of Data and Society: An Interdisciplinary Reader in Critical Data Studies, edited by Tommaso Venturini, Amelia Acker, Jean-Christophe Plantin, and Tone Walford. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529674699.n10.

Rapchak, Marcia. 2019. “That Which Cannot Be Named: The Absence of Race in the Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education.” Journal of Radical Librarianship 5: 173–96. https://journal.radicallibrarianship.org/index.php/journal/article/view/33.

Roy, Loriene (Ojibwe/Chippewa). 2015. “Indigenous Cultural Heritage Preservation: A Review Essay with Ideas for the Future.” IFLA Journal 41 (3): 192–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/0340035215597236.

Sentance, Nathan (Wiradjuri), quoted in Puawai Cairns (Ngāti Pūkenga, Ngāti Ranginui, Ngāi Te Rangi). 2018. “Museums Are Dangerous Places: How Te Papa Is Challenging Colonialist History.” The Spinoff, October 23, 2018. https://thespinoff.co.nz/atea/23-10-2018/museums-are-dangerous-places-challenging-history.

Sentance, Nathan (Wiradjuri). 2020. “Indigenous Referencing Prototype – Non-Indigenous Authored Works.” Archival Decolonist (blog), May 7. https://archivaldecolonist.org/2020/05/07/indigenous-referencing-prototype-non-indigenous-authored-works/.

Sentance, Nathan (Wiradjuri), and University of Sydney Library. 2021. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cultural Protocols. University of Sydney Library. https://doi.org/10.25910/hrdq-9n85.

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai (Ngāti Awa, Ngāti Porou, and Tūhourangi). 2012. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. 2nd ed. Zed Books.

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai (Ngāti Awa, Ngāti Porou, and Tūhourangi). 2021. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. 3rd ed. Zed Books.

Smith, Christen A., Erica L. Williams, Imani A. Wadud, Whitney N. L. Pirtle, and The Cite Black Women Collective. 2021. “Cite Black Women: A Critical Praxis (A Statement).” Feminist Anthropology 2 (1): 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/fea2.12040.

Tewell, Eamon. 2015. “A Decade of Critical Information Literacy: A Review of the Literature.” Communications in Information Literacy 9 (1): 24–43. https://doi.org/10.15760/comminfolit.2015.9.1.174.

Tewell, Eamon. 2016. “Toward the Resistant Reading of Information: Google, Resistant Spectatorship, and Critical Information Literacy.” portal: Libraries and the Academy 16 (2): 289–310. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/pla.2016.0017.

Tewell, Eamon. 2025. “Two Decades of Critical Information Literacy: A Review of the Literature.” In ACRL 2025 Conference Proceedings: Democratizing Knowledge + Access + Opportunity, 483–97. Association of College & Research Libraries. https://www.ala.org/sites/default/files/2025-03/TwoDecadesofCriticalInformationLiteracy.pdf.

Thorpe, Kirsten (Worimi), Monica Galassi, and Rachel Franks. 2016. “Discovering Indigenous Australian Culture: Building Trusted Engagement in Online Environments.” Journal of Web Librarianship 10 (4): 343–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2016.1197809.

Thorpe, Kirsten (Worimi), and Lauren Booker (Garigal). 2024. Libraries and Their Intersection with Indigenous Knowledges: Insight Report. Jumbunna Institute for Indigenous Education and Research. https://read.alia.org.au/libraries-and-their-intersection-indigenous-knowledges-insight-report.

Todd, Zoe (Métis). 2016. “An Indigenous Feminist’s Take on the Ontological Turn: ‘Ontology’ Is Just Another Word for Colonialism.” Journal of Historical Sociology 29 (1): 4–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/johs.12124.

UNDRIP. 2007. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. United Nations. https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/11/UNDRIP_E_web.pdf.

Walter, Maggie (Palawa), Raymond Lovett (Wongaibon/Ngiyampaa), Bobby Maher (Yamatji), Bhiamie Williamson (Euahlayi), Jacob Prehn (Worimi), Gawaian Bodkin‐Andrews (D’harawal), and Vanessa Lee (Yupungathi and Meriam). 2021. “Indigenous Data Sovereignty in the Era of Big Data and Open Data.” Australian Journal of Social Issues 56 (2): 143–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.141.

Younging, Gregory (Opaskwayak Cree Nation). 2018. Elements of Indigenous Style: A Guide for Writing by and about Indigenous Peoples. Brush Education.

Footnotes

1 In addition to initiatives addressing citation practices, Indigenous academics and authors have asserted rights for appropriate writing styles and attribution (Younging, Opaskwayak Cree Nation, 2018; Justice, Cherokee Nation, 2018).

2 Founded in 1978, CAVAL enables Victorian academic libraries to work collaboratively for their collective advantage. Since its inception, the organisation has become a significant contributor in the international library sector. While maintaining its commitment to member institutions, CAVAL now provides quality solutions and services to libraries and educational organisations across Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand. The CAVAL Acknowledging Cultural Authority and Indigenous Knowledges in Referencing Working Group (CACIK) was formed in early 2020 to co-create referencing guidance inclusive of Indigenous Knowledges and knowledge-sharing practices with Indigenous and settler colleagues from the galleries, libraries, archives, and museums (GLAM) sector.

3 The IKAT decision tree will be reviewed and refined in the 2026 update to improve clarity in the decision-making pathways, including clarifying the branching logic and decision points at each stage.