RESEARCH ARTICLE

Struggling with Citational Politics as a Pathway to Unlearning and Relearning for Collective Action

Christina Crespo

Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador; University of Georgia

Max Liboiron

Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador

Alex Flynn

Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador

Molly Rivers

Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador

Riley Cotter

Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador

Rui Liu

Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador

Dome Lombeida

Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador

Kaitlyn Hawkins

Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador

Nadia Duman

Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador

Abu Arif

Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador

Edward Allen

Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador

Natasha Healey

Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador

Nicole Power

Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador

Alex Zahara

Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador; Canadian Forest Service, Natural Resources Canada

John Atkinson

Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador

Paul McCarney

Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador; Yukon University

Charlie Mather

Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador

Rivers Cafferty

Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador

Lana Vuleta

Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador

Abstract

There is a growing movement committed to the values of equitable and just citation, but the material practices of altering citational politics are more challenging. For instance, researchers in the Global South are under-cited, but how many citations are enough to correct this bias? How do we best determine when an author is from the Global South to begin with? We present a case study where social and natural science researchers (the authors) spent years engaged in the material practices of citational politics at the Civic Laboratory for Environmental Action Research (CLEAR). Our findings show that there were notable changes at the individual and collective levels as participants tried to change the status quo, and we use Gloria Anzaldúa’s pathway to conocimiento as an organizing framework for explaining the process of unlearning and learning that occurs through engaging with citational politics. The pathway moves through seven non-linear stages on the way to conocimiento: (1) arrebato/the rupture, when the reality of citational politics is fully understood; (2) liminal space, characterized by more questions than answers; (3) a retreat to pre-rupture/arrebato politics in the face of difficult ideas (backsliding); (4) the crossing, a step in ethical learning that moves the learner from thinking to action; (5) creating new stories where new individual and collective norms emerge; (6) the clash, a stage where these new norms clash against the status quo again; (7) and finally chores, the mundane, regular practices that maintain an amended status quo. Our analysis of the process is designed to both support citational politics practices in particular and provide a framework with examples of how to facilitate and anticipate changes in engaged, collective social change work in general.

Keywords: praxis; epistemic justice; knowledge production; pedagogy; collective learning; feminist writing practice; critical reflexivity; collective transformation; collaborative research; material practices of scholarship; ethics; feminist epistemology

How to cite this article: Christina Crespo, Max Liboiron, Alex Flynn, Molly Rivers, Riley Cotter, Rui Liu, Dome Lombeida, Kaitlyn Hawkins, Nadia Duman, Abu Arif, Edward Allen, Natasha Healey, Nicole Power, Alex Zahara, John Atkinson, Paul McCarney, Charlie Mather, Rivers Cafferty, and Lana Vuleta. 2026. Struggling with Citational Politics as a Pathway to Unlearning and Relearning for Collective Action. KULA: Knowledge Creation, Dissemination, and Preservation Studies 9(1). https://doi.org/10.18357/kula.314

Submitted: 29 March 2025 Accepted: 31 October 2025 Published: 19 January 2026

Copyright: © 2026 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

KULA: Knowledge Creation, Dissemination, and Preservation Studies is a peer-reviewed open access journal published by University of Victoria Libraries.

Competing interests and funding: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Introduction

It seems that every time we write, no matter the year, creating and maintaining frameworks for understanding and changing the status quo is timely. One of the key lessons we have learned from doing change-oriented research and teaching is that these frameworks need to be specific: whose status quo, exactly (Liboiron 2021; Tuck and Yang 2012)? What do we mean by justice (Liboiron et al. 2023)?

The authors of this paper are or have been part of an interdisciplinary research laboratory, Civic Laboratory for Environmental Action Research (CLEAR), which develops research methods grounded in humility, accountability, and good land relations (CLEAR 2021). One of our methodological commitments is around citational politics—recognizing and changing dominant power structures that allow some forms of knowledge and knowledge holders to flourish readily, while others are repressed, through citation (Ahmed 2013; Tuck, Yang, and Gaztambide-Fernández 2015). We find that the material practice of citing differently is difficult not only because of infrastructures that make it easier to cite the status quo (Hawkins 2021; Junco 2022; Mott and Cockayne 2017), but also because citing differently requires considerable unlearning and relearning about structures of power. We focus on the latter issue here, using Chicana feminist theorist Gloria Anzaldúa’s concept of conocimiento (Anzaldúa 2015) to understand our struggles changing citational practices.

Methods

In what follows, we trace a case study where social and natural science researchers (the authors) created a working group to improve our lab’s citational practices. The text is multi-vocal, where notes from working group meetings, members’ blog posts, and co-author voices are sometimes combined into a lab-wide “we” and sometimes authors speak only for themselves. The latter are noted through block quotes and attribution with each author’s name. It was methodologically imperative to differentiate between collective and individual voices given that positionality plays a central role in our findings and CLEAR membership is diverse (as we will detail below; note that each co-author introduces themselves fully the first time they appear as an individual in the text). Author order was decided by consensus following the protocol in Max Liboiron et al. (2017).

When we write about conocimiento, we use English and Spanish consistently but unevenly. We usually use Anzaldúa’s own terms in their original languages. At the same time, given extensive critique of Anzaldúa’s appropriation of Indigenous language and concepts (e.g., Saldaña-Portillo 2001; Hooker 2014; Busey and Silva 2021), we do not use Indigenous language that does not come from Indigenous language users or communities. Despite these critiques, we collectively decided to use Anzaldúa’s work as a commitment to “citing against harm [in a way that] redirects our attention to structural oppression, building good relations, collective modes of resistance and the necessity for political mobilizations beyond individual citational practices” (Liu 2023). Finally, sometimes we do not translate Spanish into English when there is no good translation, and we do not italicize foreign language in the text (which is mainly English).

When we cite other scholarship, we privilege a researchscape led by Indigenous, Black, and gender minorities of Colour for two reasons. First, because they are simply a strong fit due to their research on or use of justice-oriented practices, often within colonial institutions. Second, we always try to cite the type of scholars that are systematically underrepresented in references lists. This also impacts how we cite; we use the Gray test (Belcher 2018) and discuss the work of women and scholars of Colour at length in the body of the text, and we use authors’ own words as much as possible, using block and direct quotes extensively. However, this does not automatically mean our modes of citing are decolonial, anti-racist, or feminist, as we will detail below (see Tuck and Yang 2012; Belcher 2018).

Conocimiento

As CLEAR set out to create practices around justice-oriented citational politics (starting with the very question of what justice means in this context!), we found that lab members underwent a complex and often difficult internal journey before citational politics could first make sense, then result in change at the individual level, and finally impact collective practices. This journey is well described by Chicana feminist scholar Gloria Anzaldúa’s concept of conocimiento (Anzaldúa 2015).

Anzaldúa’s conocimiento is a genre of learning that includes the hand, heart, and mind, and through which individual epiphanies are capable of catalyzing collective action. Conocimiento places value on the process rather than quick fixes and easy answers, even as its central commitment is to emancipatory theories of change (Anzaldúa 2015).

Anzaldúa explains that conocimiento “derives from cognoscera, a Latin verb that means ‘to know;’ it’s the Spanish word for knowledge and skill” (2015, 237). At different points in her writing, she describes it as insight, awakening, embodied spiritualities, and reflective consciousness. In all cases, conocimiento is “that aspect of consciousness urging you to act on the knowledge gained” (Anzaldúa 2015, 237). As a result, conocimiento brings together Anzaldúa’s earlier theories to develop a holistic understanding of knowledge and learning that is explicitly activist in its orientations; individual experiences are situated within the larger frame of social realities, connecting personal struggles with collective action.

Though there are many excellent frameworks for understanding knowledge for action (e.g., Marx 1867; Freire 2005; Love 2019), Anzaldúa’s pathway to conocimiento includes a description of stages of unlearning, then relearning, and finally acting as part of a collective that is particularly well suited to investigate what happened with CLEAR’s citational politics working group efforts. As the first author and working group lead, I (Christina, she/her, a PhD student at the time of writing) also chose to think with Anzaldúa because her work resonated strongly with me as a Latina. Her work has helped me make sense of the world. While there are other frameworks, such as Poka Laenui’s (2000) decolonization framework, that could also be generative here, this paper and the decisions within it are the product of a marriage between my work and CLEAR. In justice-oriented and epistemically diverse spaces such as CLEAR, theory and practice are guided by better fit rather than fixed allegiance to any one framework. This orientation resists the tendency to reduce difference “in the interests of mutuality,” which is often thought to “enable progress toward the social ideal of equality. [But] structural power differences, as well as other differences in perspective and history, are downplayed as collaborators attempt to come to some shared perspective” (Jones and Jenkins 2008, 474). In our case study, as in all projects at CLEAR, theory and practice were chosen according to what relationships, contexts, and accountabilities the project required.

Case Study: CLEAR’s Citational Politics Working Group

In 2020, CLEAR lab members set out to change our writing so it addressed baseline critiques that citation-as-usual drastically underrepresents women authors more “than would be expected if gender were unrelated to referencing” (Dworkin et al. 2020, 918; also see Block 2020; Caplar, Tacchella, and Birrer 2017; Chatterjee and Werner 2021; Dion, Sumner, and Mitchell 2018; Fulvio, Akinnola, and Postle 2021; Maliniak, Powers, and Walter 2013; Wang et al. 2021), a critique that also extends to authors of Colour (Nash 2020; Block 2020; Chakravartty et al. 2018; Czerniewicz, Goodier, and Morrell 2017). We were also interested in more nuanced politics of citation, such as whether to cite abusers (Souleles 2020; Liu 2023), value- and community-based citational practices (McAllister et al. 2022; Tierney 2020), and citation with or against disciplinary canons (Holzhauser 2021; Gregory 2020). The question was: how? We created distinct working groups based on methodological questions around gender and racial underrepresentation; the dominance of knowledge from the Global North; whether and how to cite known abusers; how to cite with humility and good relations; and how to cite differently when the agency of the author was constrained (such as in graduate student exams). What surprised us was that even though CLEAR members were already invested in social movements like feminism and values like collectivity, the premises of those values and how to enact them were called into question through our un- and re-learning.

The Pathway of Conocimiento

We use the stages of Anzaldúa’s conocimiento to understand CLEAR members’ journey to collective politics and action. El camino del conocimiento (“the pathway to conocimiento”) involves travel between seven non-linear stages, through which internal shifts in consciousness become linked to collective action (Anzaldúa 2015). The stages may occur concurrently, chronologically, or zigzag in between. Anzaldúa explains, “You’re never only in one space, but partially in one, partially in another, with nepantla occurring most often—as its own space and as the transition between each of the others” (2015, 123). In the following sections, we will use the pathway to conocimiento as an organizing framework for explaining the process of difficult learning that occurs through engaging with citational politics. Though the stages are not linear, and not all lab members had the same reactions to the same degree, the stages clarify how political awareness and capacity for collective action come into play.

1. Arrebato/The Rupture

The pathway to conocimiento begins with arrebato, an upheaval or rupture that catalyzes an eventual shift in consciousness. Anzaldúa describes this first stage as an event that pulls the “linchpin that held your reality/story together” (2015, 124)—a loss, a betrayal, a grinding down that “turns your world upside down and cracks the walls of your reality” and “jars you out of the cultural trance and the spell of the collective mind-set” (2015, 125). This rupture can shut you down or close you off, “pushing you out of your body” (Anzaldúa 2015, 153). Yet, for conocimiento, rupture can also be a site of creative possibility, rendering visible that which is normally concealed by the everyday.

For many lab members, a site of early rupture was the deepened realization that there really are structures of oppression built into citation. For example, both Molly (a master’s student working as a lab technician) and Kaitlyn (the lab manager) expressed an initial disinterest in citational politics. However, that changed after learning more about the topic. In a blog post on the topic, Molly explains her arrebato:

From my experience within the academy, I already knew about citations in regard to their importance to my career, like the importance of being cited often, of publishing in high impact journals, and the negative view of self-citation. So, when I first heard that citational politics was to be the topic of discussion at one of our lab meetings in CLEAR, my ignorance prevented me from feeling particularly engaged. After this initial lab meeting however, I found myself shocked by the importance of citation, and particularly by my lack of awareness of the impact my citing could have on others. I was especially shaken by the fact that I had never heard this discussed before, an aspect of scientific writing I now realise is so important. (Rivers 2021)

In her blog post, Kaitlyn also uses the language of “shock,” saying that learning about citational politics changed her entire thought process on it:

What I read in those assigned readings (Ahmed 2013; Powys Whyte and Hunt 2018; Mott and Cockayne 2017; Tuck, Yang, and Gaztambide-Fernández 2015; Liboiron et al. 2021; Liboiron 2020) and in other pieces that those readings led me to, completely and utterly changed my entire thought process on the subject and frankly blew my mind. It was then on that I began to learn a lot of shocking knowledge about the politics of citation. (Hawkins 2021)

For both lab members, learning about citational politics ruptured their academic teaching that citations are a neutral technology. As white women and junior scholars, their positionality likely influenced their experiences with citations, creating a deeper experience of rupture. For others occupying different identities and who are farther along in their research career, citational politics was not a new idea but rather reflected their own experiences. As CLEAR Director and Principal Investigator Max (they/them, Michif) explains,

Some of us have been unable to publish path-breaking work from non-dominant perspectives. Some have had our public intellectualism used but not cited in works by dominant actors, even as we’re celebrated by those same actors as being generous and brilliant. Most of us have been bumped down or removed from authorship on projects we are involved in. (Liboiron 2022; see also Powys Whyte and Hunt 2018)

One of Max’s arrebatos stemmed from the assumption that negative experiences of authorship or lack of attribution resulted in different citation practices. However, when they looked at the demographics of who CLEAR cited for one of our peer-reviewed articles, Max was surprised—and embarrassed—that even though “we have understood ourselves as a feminist lab since our inception, . . . when we look at one of our fairly recent papers on plastic ingestion in fish (our bailiwick research topic), we found that we cited only ~20% women authors, and nearly ~60% White authors (Liboiron et al. 2019). Intentions, even when clearly stated and revisited, are not enough to change norms” in practice (Liboiron 2022). Max assumed we (CLEAR lab) were automatically doing better than the norm, and the evidence of a stark failure created a new starting point for them.

Finally, Alex F. (part-time lab technician, mixed Inuit and settler ancestry) “woke up” to citational politics from his place-based positionality as a Northerner struggling to reconcile academic and local knowledge: I (Alex F.) was reading an article about lake trout distribution in Labrador when I came across a surprising statement. It stated that the presence of lake trout in Lac Mercier extended the species range of lake trout 65 km into the southeastern portion of Labrador. The community I am from is ~300 km southeast of Happy Valley-Goose Bay and we would often catch lake trout in the area. So clearly the species range extends more than 65 km. But I was unsure on how or if I should address this. In a blog post, Alex F. wrote,

What I consider important knowledge about lake trout was seemingly not worth a confirmation, a rebuttal, or even a mention in academia and other ‘reputable’, publicly available sources (Mott and Cockayne, 2017: 959). Where, in these official sources of knowledge, was everything that I had heard, seen, lived, and knew? I questioned the relevance and value of my own knowledge and experiences. (Flynn 2022)

I (Alex F.) began to ask myself, Should I cite my own personal experience? Do I just ignore it? Is it worth getting frustrated over? These questions, coming on the heels of arrebato, signal the start of the next stage of conocimiento: liminal space (discussed below).

In all CLEAR members’ cases of arrebatos, positionality plays a role not only in a new understanding of citational politics, but also in individual experiences with these politics and the un/learning required to move forward. It also shows how a single arrebato will not be enough for all participants in a collective to move into conocimiento, an important insight for facilitators, leaders, and mentors who wish to bring others into collective action.

2. Liminal Space

After the rupture of arrebatos, “yesterday’s mode of consciousness pinches like an outgrown shoe” (Anzaldúa 2015, 125), which can result in multiple opposing perspectives and realities existing simultaneously, intertwined through continuous dialectical encounters. This second stage of conocimiento is a liminal space that is “torn between ways” (Anzaldúa 2015, 17), the “zone between changes where you struggle to find equilibrium between outer expression of change and your inner relationship to it” (Anzaldúa 2015, 127). It is a site of constant tension through which transformation is possible, but not guaranteed. We found that many CLEAR members spent extended time in this stage, which was characterized by proliferating questions but not answers. People were often frustrated by not knowing what to do with their post-arrebatos insight.

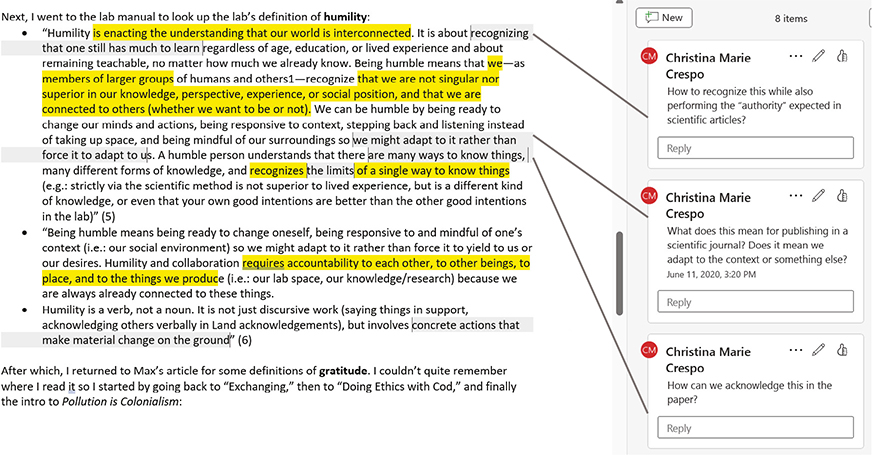

When trying to figure out how to cite with humility, I (Christina) found that what I had was a lot of questions, starting with the question of what exactly humility meant in CLEAR’s context. When I looked up the working definition of humility from the lab book, I encountered further questions, such as “How can we recognize that ‘one still has much to learn’ while also performing the ‘authority’ expected in scientific articles?” These questions were generative, leading to even more questions. Figure 1 shows that even with clarity in terms of our values or ethics, the road to praxis is not necessarily clear. In fact, it can become less clear as we start to question what we assumed we understood and had been practicing for years when brought into a new context like citation.

Figure 1. Christina’s annotations to the CLEAR Lab Book’s definition of humility in an effort to bring this value into lab-wide citation practices.

One of the working groups focused on how to cite underrepresented genders, races, and ethnicities better. Questions around classification abounded. Do you assume gender based on an author’s first name? On a profile photo? We cannot use photos to see race or ethnicity, right? Can we? Who counts as Global North versus Global South, especially if people were born in one but work in the other (for a discussion on the meaning and utility of the terms “Global North” and “Global South” that we follow here, see Mohanty 2003)? These questions only raised more questions—is an “add and stir” diversity approach really going to enact good citational politics? How many citations of women are “enough” (see Lombeida 2023 for a longer narrative describing this stage)?

The deluge of questions left us circling throughout the process. However, this liminal stage is also a place of possibility. These questions sometimes catapulted us into new forms of learning, towards conocimiento. For example, some working group members moved away from a “quota” system, where a certain number of underrepresented people ought to be cited, to thinking about how to engage with those researchers’ works within the text, akin to the Gray test, where “a journal article must not only cite the scholarship of at least two women and two non-white people but must discuss it in the body of the text” (Belcher 2018). While this shift did not sidestep or solve questions of quantitative representation, it expanded the range of citational engagement for the working group. This expansion let the working group move from a space of questions into a space of action, even if questions remained.

Yet encountering questions and the uncertainty that comes with them does not guarantee movement to the next stage. In times like these, it is hard not to fall back onto what has been deeply ingrained, on what you were trained to do through years of socialization, which brings us to the next stage of conocimiento.

3. Desconocimiento

Transformation is not an easy process. This fact is particularly apparent in the third stage of conocimiento, which refers to periods in which one might return to desconocimiento, false knowledge or not knowing, in order to avoid or retreat from the inherent struggle of transforming internal consciousness. Anzaldúa explains that this is the result of a central paradox of conocimiento, that “the knowledge that exposes your fears can also remove them” (2015, 132). It is an easy place to fall into as the result of years of socialization. We affectionately term this stage “the freak-out,” as it was often identifiable by strong, uncharacteristic behaviour or ideas accompanied by a wash of emotion.

CLEAR’s citational experiment showed that one strategy that members used to deal with the hesitation, confusion, and frustration of liminal space was to grasp for concrete frameworks, even when those frameworks did not serve the politics we were after. In the first working group meetings, multiple lab members talked about not knowing how to do “it,” not knowing what we were “allowed to do.” These concerns were brought back to the main lab meeting in the form of requests for clarifications about the rules for citational politics. Max responded by saying, “There should not be any rules. If you are stopped by a rule, think [about] where it comes from. Write that down. We will figure out why those [assumed] rules are there and where the wiggle is.”

During a check-out at the end of this meeting, Molly expressed that it was nice to know that other people were encountering challenges. Max explained that tracking our moments of failure or specific confusion is part of our findings in this citational experiment. We left that meeting ready to get back into our working groups. What I (Max) found interesting about this set of interactions is that even though there was a lab-wide consensus at the outset that we were changing norms and that the experiment was open ended, when CLEAR members had extensive agency (something they often critique in other research spaces and request in CLEAR), they wanted more guidelines and even rules. After speaking with many CLEAR members about this tendency over the years, I (Max) think this comes from a fear of failure, so if facilitators or mentors are looking to guide people through an unlearning and relearning process, a framework for failure is crucial for both anticipating and then moving people through desconocimiento.

As another example of desconocimiento, one white lab member’s politics shifted in a moment of frustration. Riley (a lab technician at the time, now a master’s student) was working on a research article where knowing whether an author was Indigenous was central to analysis (Liboiron and Cotter 2023). He found that because a lot of authors did not self-identify, there was a lot of uncertainty. I (Riley) had taken a course with Max that talked a lot about position statements and the notion that identity impacts knowledge and research, which really resonated with me. I thought, If everyone just had a position statement in every text we could avoid this kind of issue. I began to write a blog post for the citational politics project that advocated a utopia where everyone realized that their identity matters to their research and included a position statement in every paper.

Not the best idea, obviously. Christina (very generously and politely) explained to me that a lot of people do not self-identify because it is not safe or is not the best idea (especially in academia). I knew that, of course, even from my lived experience as a queer person. Max and I later discussed how queer people conceal and reveal parts of their identity all the time to navigate uncertain or unfriendly spaces.

What is particularly surprising about this moment of desconocimiento for me (Riley) is that it goes against my lived experience, so much so that I chose graduate work about how universalism is not a very robust concept for justice-based work. But after completing a very typical Western science undergraduate degree, my plane of thinking was still slanted toward wanting unmitigated access to all forms of knowledge to the point that I slid back into that paradigm. I was not the only one: One lab member appealed to stronger binaries, advocating a position where “you’re from Global South or you’re not” during a working group meeting (this position did not last long).

That these statements were not just possible but adamant in a lab that specializes in non-binary analyses (Shepherd 2018) and has multiple non-binary gender minority members shows how desconocimiento may look like a backslide, a militant return to aspects of the status quo. But desconocimiento is a necessary part of the unlearning and relearning process, not its failure. That is, unless the journey stops here, which is possible. Many scholars have pointed out how justice-oriented efforts often fall into desconocimiento and dig in, aborting emancipation and becoming “a legitimizing strategy” that allows that status quo to flourish, this time with more rainbows (Nash 2019, 18; see also Ahmed 2012).

As such, it is crucial from a facilitating perspective to anticipate and work through these moments as a stage of unlearning rather than a defeat. From a un/learner perspective, it means having reflexive and supportive structures (not just intent!) to help one recognize when this happens so that the process does not end here. CLEAR did the latter through having a diverse collective work together, as Riley and Max’s stories show. Part of the next space of conocimiento is the recognition that you likely need help to transform, that it is important to listen and consider new ways of being and understanding.

4. The Crossing

This brings us to the fourth stage, the crossing, in which one begins to move into a new identity, a new understanding of the world. In this stage, “you open yourself up and listen,” moving from thought to action by asking what you can contribute, what you can do, as a fundamental step in ethical learning (Anzaldúa 2015, 136). As you cross a bridge into something else, you might leave pieces of yourself, your story, and “erroneous bits of knowledge” behind (Anzaldúa 2015, 137). As mentioned above, this process requires some help.

The CLEAR project supported this difficult stage in several ways. We had facilitated conversations with peers in our working groups and the project team overall; dedicated readings assigned by Max when they saw a particular struggle happening; and the option to write blog posts that allowed us to reflect at length and/or concretize each person’s learning. These supports were always tied to moments in the desconocimiento stage, where CLEAR members recognized they had backslid and were looking for ways to address it.

For instance, Rui (a social science research assistant of Colour) chose to focus on the difficult issue of whether, whom, and how to not cite. Rui and the lab’s first (and celebrated!) orientation to citational exclusion was Sara Ahmed’s approach to not cite (the institution of) white men (2014, 2017; see also Usher 2018 and Leiter 2018 for more politics of exclusion). But after reading Katherine McKittrick’s Dear Science and Other Stories (2021), a hallmark moment in the project, many lab members changed their orientation to something more complex. Rui writes,

McKittrick’s work in Dear Science and Other Stories pushes us to think beyond exclusion and exclusion’s “impossible foreclosures.” She crucially asks: “Do we unlearn whom we do not cite?” Although I stand by exclusion as a strategic tool for accountability, as a theory of change, exclusion hinges upon individualistic and liberal understandings of agency. Reorienting our focus to collective intellectual praxis challenges the illusion of individualized knowledge production and individual “choice” and shifts our energies to building the kinds of intellectual communities we want to be a part of. Thinking about Black collaborative ways of knowing, McKittrick argues that the “works cited” lists of Black studies, “when understood as in conversation with each other, demonstrate an interconnected story that resists oppression.” (Liu 2023)

Not only did Rui “get past ‘the binary of cite or not cite’” (Liu 2023) into more complex and collective practices of citations, but she also found she did not have to resolve all her questions about citing abusers. Her final blog post is roughly half the size of her initial draft, as she found she did not know how to deal with some of the ethical conundrums she found about different types of justice whose different concepts of right and wrong called for mutually exclusive action. Yet, the blog post has a clear ethic and proposals for action.

Rui’s blog post illustrates how engaging with citational politics can be a generative form of learning. By accepting that there are no easy answers, Rui instead provides a toolkit, “a mixed bag of strategies that foreground accountability and structural violence” (2023). While they are not rules—CLEAR members have let go of that impulse by this stage—the tools give insights into how these problems might lead to “a reorientation to how we think about attribution, credit, and the project of knowledge production” (Liu 2023). The tools orient us towards conocimiento, towards new personal and collective stories.

5. Creating New Stories

Anzaldúa describes the fifth stage of conocimiento as creating “new personal and collective ‘stories,’” ones that provide an option for relating to the status quo in ways other than assimilation or separation (2015, 138). She explains that through this process of examining the world often taken for granted, the dominant paradigm loses footing as the “only true, impartial arbiter of reality” (Anzaldúa 2015, 140). In developing a more expansive consciousness, it is necessary to attend to multicultural narratives, ones that “must partially come from outside the system of ruling powers” (Anzaldúa 2015, 140) though they may also strategically “relocate selective features of the older frameworks within the new ones” (Harding 2016, 1078).

While Anzaldúa treats individual and collective stories as two parts of one step, we found that they were quite separate and that the creation of a new individual story did not always mean a new collective story as well. Perhaps these cases are just a return to the freak-out/desconocimiento as learning veers back to the familiarity of individualism, where the individual is the best and truest unit of knowledge and change. But this does not fit quite right: Even in the rare cases where this occurred, people were usually still newly oriented to forms of collective life compared to before.

For example, Molly’s blog post highlights an internal shift that she shares with another person, but does not necessarily lead to a new collaborative path:

So, after taking a very extended lunch break in which my roommate and I expressed our disbelief at our ignorance, marveled at the injustice of this system and combed over our own reference lists to see how inclusive we were (unsurprisingly, not very), we both resolved to try harder in all future work. But why is this not a commonly discussed issue for all graduate and undergraduate students? We should, as a [rite] of passage into academia, be made aware of the consequences of our academic actions (in a viewpoint of our impacts on others) and given tools to help us work through this issue. (Rivers 2021)

While Molly’s experience does not end here, we can see how this is where conocimiento might stay: with a new individual, albeit shared, story.

In contrast, Rui’s case shows a clear link between an individual shift that leads to a new collective story. In a turn to conocimiento, she asks,

How might our protocols for citing against harm shift when we turn away from an individualistic understanding of authorship that frames knowledge as intellectual property to an understanding of knowledge production as an inherently collective endeavor? (Liu 2023)

Rui’s blog post provides one example of how struggling through citational politics generated a new understanding of citation as collective praxis rather than something individual authors choose to engage with within the domain of their works cited lists.

Max likewise centered a blog post on citational practices in shared spaces where individual agency is not paramount. They focused on a particular sphere of citation, on citing in “tight spaces” where there is not much flexibility for what and how you might be able to cite, where “not only the norms of citation (of the canon) but also the structure of the knowledge or research overdetermines what might be done” (Liboiron 2022). These tight spaces are things like baseline studies or comprehensive exams—places where the wiggle room for agency is small and institutional forms of knowledge play a larger role than individual researcher agency, but where individual agency persists, even as it is overdetermined by dominant structures like the canon, the response to reviewers, or the exam.

Max provides tangible tactics for how to navigate these spaces of citation that provide an option for relating to the status quo other than assimilation or separation, a hallmark of the fifth stage of conocimiento. They explain,

CLEAR believes in critiques of citation and referencing, but we’re still scientists in the dominant tradition of Western science. At the end of the day, we still put on our lab coats, write papers, and need to cite knowledge about plastic pollution, including baseline studies. We are committed to the question of how to cite differently in these tight places. (Liboiron 2022)

Max’s quote highlights how new stories can be situated inside dominant narratives without necessarily changing that dominance (though that is also a goal). Some of their examples, drawn from the CLEAR citation project, include citing from a range of disciplines, incorporating important elements in articles designed for later self-citation, and citing knowledge that is not in written forms (Liboiron 2022). Such tactics are less about tearing structures down and more about using widely shared structures to do good work:

The issues and tactics we outline here are dedicated to working within these tight spaces rather than fantasizing our ways outside of them. Thinking with la paperson’s A Third University is Possible (2007), we are not interested in citations that have [achieved] good relations as if they are settled, but rather citations that enact good relations, even when they are still in problematic structures and standards. We hope this experiment in finding our way through a tight space is useful to your own efforts at change. (Liboiron 2022)

With new ideas and stories about citation in hand, CLEAR took the next step by sharing what they learned beyond the laboratory collective. Some of the blog posts rewrote individuals’ stories and their relations to citations. Other blog posts asked what new collective stories look like. Both are part of the process. But what happens when these new narratives move outside of the lab? What happens when others are confronted with the stories?

6. The Clash

The sixth stage of conocimiento is “the blow-up . . . a clash of realities” (Anzaldúa 2015, 147). Anzaldúa explains that “new conocimientos (insights) threaten your sense of what’s ‘real’ when it’s up against what’s ‘real’ to the other. But it’s precisely this threat that triggers transformation” (2015, 147). Anzaldúa acknowledges that in bringing new realities to bear, conflict will inevitably ensue.

Sometimes it just comes down to haters are going to hate. However, it can also be an opportunity, where the resistance from someone else might trigger their own conocimiento. As a CLEAR member, I (Christina) am sheltered from a lot of this blowback by Max and the lab managers. It is how the lab is intentionally designed. Max explained how the lab is supposed to work so “shit rolls uphill”; those in leadership and managerial positions work out the hardest and harshest issues. I know Max gets some major hate mail in response to CLEAR’s work. I get to be spared from that, though. It is one of the benefits of having someone “drive the bus,” so to speak. Max is accountable for the lab, and dealing with the conflict brought on by others is one of the ways they enact their accountability.

One of the questions that I (Riley) and other CLEAR members get at almost every conference presentation is “Have you had any pushback for the kind of work you do?” Whether they mean pushback from funders or other scholars or university administrators, people want to hear about the clash. This kind of wondering makes sense: People figure that research that works against the status quo must bear some conflict with proponents or custodians of normalcy. Our answer to the question about whether we get pushback is usually, “Not really.” This answer can seem unsatisfactory, unlikely, or even unbelievable. But it is true that our clashes are mostly about our work running up against structural barriers and norms that are difficult to augment (e.g., Hawkins 2021) rather than any particular person or institution having a problem with our work.

We believe that one of the reasons people ask about pushback is the conflation between institutional change and change within the CLEAR collective. CLEAR is certainly an unusual lab within academia, but it is so because it is a clearly demarked space with boundaries that are well respected by the university. This status allows us to experiment at the scale of the lab as well as create the safer space to do so. While different lab members do engage in institutional change, CLEAR generally does not, and neither did the citational politics project. In the spirit of Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang’s (2012) insistence that theories of change not be conflated so as to best meet the goals, we wish to clarify that social change must not scale up in order to be social change. At the same time, most lab members have attempted to bring CLEAR practices into new spaces not designed for them.

I (Paul, he/him, white settler working for Indigenous Governments) have designed projects to bring things I have learned in the CLEAR lab, including how to bring a team together, to other spaces. For example, after reading a CLEAR paper on models of justice evoked in plastics research (Liboiron et al. 2023), I was interested in conducting a similar review that looked at models of justice in wildlife co-management literature, a field I have spent time studying and working in. Starting a project that was directly based on a previous project from the CLEAR lab allowed me to extend and amplify the values and methodologies that structure CLEAR in a new project. I hoped that explaining how the review was directly inspired by and sought to replicate the original paper’s framing and methods would allow me to stand alongside the CLEAR lab, even in the face of any potential questioning or pushback. The pushback never came, however. The continuity between the two projects provided a point to crystallize a group of people to work on the project who understood and wanted to organize around a set of shared values and methods. So, while I have experienced questioning and even some pushback in the past when trying to implement lessons and values I have learned in the CLEAR lab, I have also learned how to carefully and purposefully construct projects that bring people together who embrace CLEAR values and want to see them guide other work.

At the same time, I (Max) hear from CLEAR alumni that when they go onto further studies or the professional field, they struggle with having their voices heard, including how and whom they want to cite. Sometimes we hear that they make headway in their new labs with considerable effort and energy, and sometimes we hear they do not. One example of the latter is Molly’s story after she graduated: It is a new lab, a new institution, a new country. I (Molly) am in an online working group at an introductory event for new PhD students, only a few weeks into my PhD programme, and we start discussing best practices for writing papers, for structuring your abstract, for labelling your figures, for citing your references. I feel a tug at the back of my mind: Should I bring up my recent experience and new stance on citational politics? Will it be met with understanding or bemusement? Will it be met with interest or dismissal? Will I be seen as an open-minded or difficult student? I try. I am met with blank faces, not unkind, but relatively uninterested. The conversation quickly moves on. Better luck next time, I guess.

This clash is one of the reasons that I (Max) spend considerable time on theories of change that do not require broad, structural agency: Many of our lab members move into professional spaces where their “new personal and collective ‘stories’” do not find fertile ground. This is why I think Anzaldúa’s conocimiento has promise as a model of change: The clash stage requires some skill in strategically “relocat[ing] selective features of the older frameworks within the new ones” (Harding 2016, 1078).

7. Chores

The end of Anzaldúa’s pathway is acting out the “final” vision, which is really just more beginnings, branches, sideshoots, and backtracking (2015, 149) into new and renewed conocimiento. Anzaldúa explains that what happens at the end is “the critical turning point of transformation” (2015, 123). Yet it does not have a stage or set of actions that accompany it. This final step is central to CLEAR’s mission to do science differently. We take the mundane, everyday, material labour of acting out the vision, sometimes against the clash, sometimes within the collective, and usually in between, as our central form of activism. Put another way, for CLEAR, the last stage of un/learning is doing your chores: mundane, material actions that have more to do with maintenance of a better status quo rather than rupture or revolution, though of course revolutions have their chores.

For citational politics, this means writing up a formal protocol on citation, maintaining a library of research we want to be engaging with and that new members have to be trained in, creating evaluations of how well we are doing, and citing. Lots and lots of citing. Alex Z. (white, queer, PhD student working for an Indigenous Council), recalls that, while drafting my dissertation I (Alex Z.) continued to have conversations with Max and Nicole [two of my committee members who were also in the citational politics working group] about citational politics, and included a section on citation in my methods section, citing CLEAR’s work. For me, these dissertation discussions felt like an extension or different iteration of the citational politics work in some way. Alex Z.’s chores mean remembering these conversations, writing notes on them, making a plan to carry them out, and then citing, citing, and citing, outlining and reoutlining the words around those citations so they flow and are clear. In his dissertation, Alex Z. writes that

When discussing experiences or interpretations of Indigenous people or Nations on topics, including wildfire or colonization in Saskatchewan, I quote directly from Indigenous sources rather than settler interpretations of Indigenous knowledge or people (see also Christanson et al. 2022). I do so for two reasons: first, to ensure theorization “stands with” (cf Tallbear 2014) those who are working against colonialism in this place; and second, to not repeat potential misrepresentations of Indigenous people, their knowledge and concerns, as is prevalent in settler scholarship (Smith 2012). . . . The citational politics followed in this dissertation aims to “enact good relations, even when they are still in problematic structures and standards” (Liboiron with Liu 2022: np) as a method of settler-led, place-based, anti-colonial research. (Zahara 2024, 90–91)

Alex F. has also reflected on the chores that came with changing citational relations. When I (Alex F.) started writing up my citational politics blog post, I was unaccustomed to the extra steps and necessary communications needed when citing people from my own community. Normally, citing is just finding and reading articles online with no need to interact with anyone. However, for this project I had to talk to people, explain what I was doing, what it was for, get their feedback, get their consent, and have a drink with them. One person gave me back a handwritten letter and I could not read some of what they wrote, so I had to reconfirm with them. I am glad CLEAR encourages using non-academic sources, as it opens up new paths to take when conducting research and helps counter the idea that researchers need to be outside observers. At the same time, it requires considerably more material labour. In a similar vein, CLEAR is currently writing a paper about plastic ingestion in ringed seal and Arctic char in Nunatsiavut, and we started with citations. The first step in writing was not a brainstorm about our big ideas, but a cloud-based spreadsheet where different quotes from writings by Nunatsiavummiut (people of Nunatsiavut) were copied, linked, and put in priority order. There was a lot of follow-up to make sure lab members kept the page numbers with their quotes (still, they were not and had to be fetched later).

When I (Alex F.) was updating the spreadsheet, many hours were spent reading, finding quotes, referencing the work correctly, finding the correct page number for the quote, making sure other examples were up to date and accurate, addressing repeats (two papers saying the same thing or the same information from one paper repeated), and trying to find if the information could be found from non–dominant white heteronormative sources. Like with most spreadsheet work, there is a lot of tediousness, but it was really cool when you did find a non-dominant source or a great quote.

The chores continued after the spreadsheet, though. Someone had to be responsible for making sure that prioritization was not overridden when a lab member with training in a disciplinary canon wrote up or revised a section. There is an important unpublished community-based report that does not have a final author order, and a lab member has sent countless emails, set up several times to meet, and chased down project leads to get the author list so we can cite it properly. We still do not have it. The result is a paper where Inuit co-authors, projects, words, and their citations carry the tune, and the labour looks different as a result. By changing what chores were done and then putting in the labour to do them, the citational vision we reached as a lab has come to fruition.

Alex Z., Alex F., and CLEAR’s chores—what material actions they did to create and maintain good citations—evolved on their own but in parallel paths as logical extensions of the unlearning and relearning that the citational politics working group engendered. In these examples, we can see how chores can be understood as the work of making “new personal and collective ‘stories’” in the fifth stage of conocimiento (Anzaldúa 2015, 138). When we say new stories allow us to relate the status quo other than through assimilation or separation, we mean those relations manifest in chores, not just in internal reorientations or commitments. Social change is material.

Conclusion

I’m always glad when people raise a fist against the injustices of systems . . . but I’d much prefer they raise a shovel—or [bibliographic software]—with the other hand and get to work. (Liboiron 2021, 37)

The trajectory of conocimiento from a dramatic rupture to mundane chores is an important one when the end goal is making new normals, or “doing otherwise” (Star 1990). World-making might entail a cinematic bang, but world-maintaining the new order—the goal of social and political change—is chores. Crucially.

Those chores will be different for different worlds. Conocimiento has different end points because there are different kinds of visions for good. Maori citational politics (Burgess, Cormack, and Reid 2021) must have a different set of un/learnings than citing “Like a Badass Tech Feminist Scholar of Color” (Guzmán and Amrute 2019).

At the same time, here are predictable moments in conocimiento around citational politics that advisors, mentors, and facilitators can prepare for:

- Arrebato/the rupture can be facilitated with statistics and case studies about the problem of citational politics, even for those who are already onside politically. “The Gender Bias in Academe: An Annotated Bibliography of Important Recent Studies” (2017), maintained by Danica Savonick and Cathy Davidson, is a great resource. CLEAR also maintains a public library that includes similar studies as well as theory. Structured self-reflection on citational bias is also great, for which we recommend Jane Sumner’s Gender Balance Assessment Tool. We find that most academic writing anticipates this step in the process.

- The liminal space benefits from exposure to precedents and techniques from other citational politics projects as well as clarification of what variety of “good” citational politics would be (such as the example of Maori versus feminist of Colour politics above). Some of the blog posts from the CLEAR Citational Politics Working Group or the Cite Black Women Collective may help with that.

- Desconocimiento requires patience and strong facilitation. This step requires reframing backsliding as unlearning rather than failure. We found that a diverse set of collaborators who can nudge people into reflexivity through co-editing, mixing up memberships of working groups, and regular check-ins with advisors helped support this particularly difficult stage.

- The crossing was strengthened by dedicating readings and other deeper engagement for areas where desconocimiento is pooling, such as McKittrick’s essay in Dear Science and Other Stories (2021). Some of this was lab wide, and some was accomplished through research for long-form blog posts on particular topics. CLEAR’s public citational politics library may have some of these resources.

- Creating new stories is exemplified by creating and signing onto citational politics manifestos such as Critical Ethnic Studies’ “Citation Practices Challenge” (Tuck, Yang, and Gaztambide-Fernández 2015), joining other citational politics movements, or creating similar projects in new spaces.

- Finally, chores include creating protocols, templates, libraries, and evaluative criteria for keeping on track. Max has a teaching module for doing this in a classroom setting (Liboiron 2023).

Good luck, and very best wishes!

Acknowledgements

CLEAR’s citation politics project was supported by Dorothy Killam Foundation Fellowship (Akihtam), SSHRC Insight grants #435-2022-0310 & # 435-2017-0567, Memorial University’s MUCEP program, and Discovery Horizons (NSERC) DH-2022-00313.

References

Ahmed, Sara. 2012. “On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life.” In On Being Included. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822395324.

Ahmed, Sara. 2013. “Making Feminist Points.” Feministkilljoys (blog). September 11. https://feministkilljoys.com/2013/09/11/making-feminist-points/.

Ahmed, Sara. 2014. “White Men.” Feministkilljoys (blog). November 4. https://feministkilljoys.com/2014/11/04/white-men/.

Ahmed, Sara. 2017. Living a Feminist Life. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822373377.

Anzaldúa, Gloria. 2015. Light in the Dark = Luz En Lo Oscuro: Rewriting Identity, Spirituality, Reality. Duke University Press.

Belcher, Wendy (@WendyLBelcher). 2018. “To pass the Gray test, which I named after Kishonna Gray who invented the hashtag #citeherwork in 2015, a journal article must not only cite the scholarship of at least two women and two non-white people but must discuss it in the body of the text. #12WeekArticle #acwri #PhD.” Twitter. https://web.archive.org/web/20220526205736/https://twitter.com/WendyLBelcher/status/1019319858465517570.

Block, Sharon. 2020. “Erasure, Misrepresentation and Confusion: Investigating JSTOR Topics on Women’s and Race Histories.” DHQ: Digital Humanities Quarterly 14 (1). https://dhq.digitalhumanities.org/vol/14/1/000448/000448.html.

Burgess, Hana, Donna Cormack, and Papaarangi Reid. 2021. “Calling Forth Our Pasts, Citing Our Futures: An Envisioning of a Kaupapa Māori Citational Practice.” MAI Journal 10 (1): 57–67.

Busey, Christopher L., and Carolyn Silva. 2021. “Troubling the Essentialist Discourse of Brown in Education: The Anti-Black Sociopolitical and Sociohistorical Etymology of Latinxs as a Brown Monolith.” Educational Researcher 50 (3): 176–86. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X20963582.

Caplar, Neven, Sandro Tacchella, and Simon Birrer. 2017. “Quantitative Evaluation of Gender Bias in Astronomical Publications from Citation Counts.” Nature Astronomy 1 (6): 0141. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-017-0141.

Chakravartty, Paula, Rachel Kuo, Victoria Grubbs, and Charlton McIlwain. 2018. “# CommunicationSoWhite.” Journal of Communication 68 (2): 254–66. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqy003.

Chatterjee, Paula, and Rachel M. Werner. 2021. “Gender Disparity in Citations in High-Impact Journal Articles.” JAMA Network Open 4 (7): e2114509. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.14509.

Christianson, Amy Cardinal, Colin Robert Sutherland, Faisal Moola, Noémie Gonzalez Bautista, David Young, and Heather MacDonald. 2022. “Centering Indigenous Voices: The Role of Fire in the Boreal Forest of North America.” Current Forestry Reports 8 (3): 257–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40725-022-00168-9.

CLEAR. 2021. CLEAR Lab Book: A Living Manual of Our Values, Guidelines, and Protocols. V.03. Civic Laboratory for Environmental Action Research, Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5450517.

Czerniewicz, Laura, Sarah Goodier, and Robert Morrell. 2017. “Southern Knowledge Online? Climate Change Research Discoverability and Communication Practices.” Information, Communication & Society 20 (3): 386–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1168473.

Dion, Michelle L., Jane Lawrence Sumner, and Sara McLaughlin Mitchell. 2018. “Gendered Citation Patterns across Political Science and Social Science Methodology Fields.” Political Analysis 26 (3): 312–27. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2018.12.

Dworkin, Jordan D., Kristin A. Linn, Erin G. Teich, Perry Zurn, Russell T. Shinohara, and Danielle S. Bassett. 2020. “The Extent and Drivers of Gender Imbalance in Neuroscience Reference Lists.” Nature Neuroscience 23 (8): 918–26. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-020-0658-y.

Flynn, Alex, with Rui Lui, Max Liboiron, Kaitlyn Hawkins, and Molly Lahn Rivers. 2022. “Catching an Authentic Lake Trout: Knowledge Legitimization in Academia.” CLEAR (blog), June 12. https://civiclaboratory.nl/2022/03/22/catching-an-authentic-lake-trout-knowledge-legitimization-in-academia/.

Freire, Paulo. 2005. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Continuum.

Fulvio, Jacqueline M., Ileri Akinnola, and Bradley R. Postle. 2021. “Gender (Im) Balance in Citation Practices in Cognitive Neuroscience.” Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 33 (1): 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_01643.

Gregory, Chase. 2020. “(Ex)Citation: Citational Eros in Academic Texts.” Diacritics 48 (3): 60–74. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/dia.2020.0019.

Guzmán, Rigoberto Lara, and Sareeta Amrute. 2019. “How to Cite Like a Badass Tech Feminist Scholar of Color.” Medium, August 22. https://medium.com/datasociety-points/how-to-cite-like-a-badass-tech-feminist-scholar-of-color-ebc839a3619c.

Harding, Sandra. 2016. “Latin American Decolonial Social Studies of Scientific Knowledge: Alliances and Tensions.” Science, Technology, & Human Values 41 (6): 1063–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243916656465.

Hawkins, Kaitlyn. 2021. “The Researchers That Search Engines Make Invisible.” CLEAR (blog). June 10. https://civiclaboratory.nl/2021/06/10/the-researchers-that-search-engines-make-invisible/.

Holzhauser, Nicole. 2021. “Who Gets to Be a Classic in the Social Sciences?” LSE Impact Blog. The London School of Economics and Political Science, October 18. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2021/10/18/who-gets-to-be-a-classic-in-the-social-sciences/.

Hooker, Juliet. 2014. “Hybrid Subjectivities, Latin American Mestizaje, and Latino Political Thought on Race.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 2 (2): 188–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2014.904798.

Jones, Alison, and Kuni Jenkins. 2008. “Rethinking Collaboration: Working the Indigene-Colonizer Hyphen.” In Handbook of Critical Indigenous Methodologies, edited by Norman K. Denzin, Yvonna S. Lincoln, and Linda Tuhiwai Smith. SAGE.

Junco, Clara del. 2022. “A Weighty Footnote.” Inside Higher Ed. April 4, 2022. https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2022/04/05/raise-racist-scientific-history-science-papers-opinion.

Laenui, Poka. 2000. “Processes of Decolonization.” In Reclaiming Indigenous Voice and Vision, edited by Marie Ann Battiste. UBC Press.

Leiter, Brian. 2018. “Academic Ethics: Should Scholars Avoid Citing the Work of Awful People?” The Chronicle of Higher Education, October 25. https://www.chronicle.com/article/academic-ethics-should-scholars-avoid-citing-the-work-of-awful-people/.

Liboiron, Max. 2020. “Exchanging.” In Transmissions: Critical Tactics for Making and Communicating Research, edited by Kat Jungnickel. The MIT Press.

Liboiron, Max. 2021. Pollution Is Colonialism. Duke University Press.

Liboiron, Max. 2022. “Citational Politics in Tight Places.” CLEAR (blog). March 2. https://civiclaboratory.nl/2022/03/02/citational-politics-in-tight-places/.

Liboiron, Max. 2023. “Citational Politics Training Module.” CLEAR (blog). August 8. https://civiclaboratory.nl/2023/08/08/citational-politics-training-module/

Liboiron, Max, Justine Ammendolia, Katharine Winsor, Alex Zahara, Hillary Bradshaw, Jessica Melvin, Charles Mather, Natalya Dawe, Emily Wells, France Liboiron, Bojan Fürst, Coco Coyle, Jacquelyn Saturno, Melissa Novacefski, Sam Westscott, and Grandmother Liboiron 2017. “Equity in Author Order: A Feminist Laboratory’s Approach.” Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 3 (2). https://doi.org/10.28968/cftt.v3i2.28850.

Liboiron, Max, and Riley Cotter. 2023. “Review of Participation of Indigenous Peoples in Plastics Pollution Governance.” Cambridge Prisms: Plastics 1:e16. https://doi.org/10.1017/plc.2023.16.

Liboiron, Max, Rui Liu, Elise Earles, and Imari Walker-Franklin. 2023. “Models of Justice Evoked in Published Scientific Studies of Plastic Pollution.” Edited by Yann Joly. FACETS 8 (January):1–34. https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2022-0108.

Liboiron, Max, Emily Simmonds, Edward Allen, Emily Wells, Jessica Melvin, Alex Zahara, and Charles Mather. 2021. “Doing Ethics with Cod.” In Making and Doing: Activating STS through Knowledge Expression and Travel, edited by Gary Lee Downey and Teun Zuiderent-Jerak. The MIT Press.

Liu, Rui. 2023. “Citing Toward Community, Citing Against Harm.” CLEAR (blog). March 20. https://civiclaboratory.nl/2023/03/20/citing-toward-community-citing-against-harm/.

Lombeida, Dome. 2023. “The Mental Tangles of Classification - CLEAR - Civic Laboratory for Environmental Action Research.” CLEAR (blog). March 31. https://civiclaboratory.nl/2023/03/31/the-mental-tangles-of-classification/.

Love, Bettina L. 2019. We Want to Do More than Survive: Abolitionist Teaching and the Pursuit of Educational Freedom. Beacon ress. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=r5ZgDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=We+Want+to+Do+More+than+Survive:+Abolitionist+Teaching+and+the+Pursuit+of+Educational+Freedom&ots=Uo_2bop1rt&sig=HzwD_buGChRQNhan18HCk_dHkbY.

Maliniak, Daniel, Ryan Powers, and Barbara F. Walter. 2013. “The Gender Citation Gap in International Relations.” International Organization 67 (4): 889–922. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818313000209.

Marx, Karl. 1867. Capital. Vol. I. Penguin/New Left Review.

McAllister (Te Aitanga A Māhaki), Tara, Sereana Naepi (Naitasiri/Palagi), Leilani Walker (Whakatōhea), Ashlea Gillon (Ngāti Awa, Ngāpuhi, Ngāiterangi), Patricia Clark (Ngāpuhi), Emma Lambert (Ngāti Mutunga, Ngāti Tama), Alana B. McCambridge, Channell Thoms (Ngāi Tahu -Ngāti Kurī, Ngāi Tūhoe), Jordan Housiaux (Ātiawa ki Whakarongotai, Ngāti Toa, Ngāti Raukawa, Te Atihaunui a Pāpārangi), Hanareia Ehau-Taumaunu (Ngāti Uepōhatu, Ngāti Porou, Te Ātiawa, Te Whānau-ā-Apanui), Charlotte Joy Waikauri Connell (Atihaunui a Pāpārangi, Ngāti Tama, Tūwharetoa), Rawiri Keenan (Te Atiawa, Taranaki), Kristie-Lee Thomas (Ngāti Mutunga o Wharekauri, Te Ātiawa, Ngāi Tohora, Rapuwai), Amy Maslen-Miller (Samoan), Morgan Tupaea (Ngāti Koata, Ngāti Tiipa, Ngāti Kuia, Te Aitanga a Māhaki, Ngāti Mūtunga), Kate Mauriohooho (Ngāti Raukawa ki Wharepuhunga, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Maniapoto, Waikato), Christopher Puli’uvea, Hannah Rapata (Kāi Tahu), Sally Akevai Nicholas (Ngā Pū Toru -’Avaiki Nui), Rere-No-A-Rangi Pope (Ngā Ruahine), Sangata A. F Kaufononga, Kiri Reihana (Nga Puhi, Te Rarawa, Te Whakatōhea, Ngai Tūhoe), Kane Fleury (Te Atiawa, Taranaki), Nathan Camp (Samoan), Georgia Mae Rangikahiwa Carson (Ngāti Whakaue), Jasmine Lulani Kaulamatoa (Tongan/Pālangi), Zaramasina L. Clark (Tongan/Pālangi), Mel Collings (Te Rarawa), Georgia M. Bell (Ngāti Maniapoto, Pare Hauraki), Kimiora Henare (Te Rarawa, Te Aupōuri), Kylie Reiri (Ngāti Kahungunu, Rangitāne, Ngāi Tahu), Punahamoa Walker (Whakatōhea), Kirita-Rose Escott (Ngāti Kahungunu, Samoan, Palagi), Jaye Moors, Bobbie-Jo Wilson (Ngāti Tūwharetoa), Olivia Simoa Laita (Samoan, German), Kimberley H. Maxwell (Te Whakatōhea, Te Whānau-a-Apanui, Ngāitai, Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Tūwharetoa), Stephanie Fong (Ngā Puhi), Riki Parata (Te Atiawa ki Whakarongotai, Kai Tahu, Kati Mamoe, Kati Kuri), Morgan Meertens, Connor Aston (Tangahoe, Ngāti Ruanui), Yvonne Taura (Ngāi Te Rangi, Ngāti Ranginui, Ngāti Hauā, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Uenuku), Nicole Haerewa (Ngāti Porou), Helena Lawrence (Samoan/Tokelauan/Pālangi), and Theresa Alipia. 2022. “Seen but Unheard: Navigating Turbulent Waters as Māori and Pacific Postgraduate Students in STEM.” Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 52 (sup1): 116–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/03036758.2022.2097710.

McKittrick, Katherine. 2021. Dear Science and Other Stories. Duke University Press.

Mohanty, Chandra. 2003. “‘Under Western Eyes Revisited’: Feminist Solidarity Through Anticapitalist Struggles.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 28 (2): 499–535. https://doi.org/10.1086/342914.

Mott, Carrie, and Daniel Cockayne. 2017. “Citation Matters: Mobilizing the Politics of Citation toward a Practice of ‘Conscientious Engagement.’” Gender, Place & Culture 24 (7): 954–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2017.1339022.

Nash, Jennifer C. 2019. Black Feminism Reimagined: After Intersectionality. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478002253.

Nash, Jennifer C. 2020. “Citational Desires: On Black Feminism’s Institutional Longings.” Diacritics 48 (3): 76–91. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/dia.2020.0020.

Powys Whyte, Kyle, and Sarah Hunt. 2018. “The Politics of Citation: Is the Peer Review Process Biased against Indigenous Academics?” CBC Radio. https://www.cbc.ca/radio/unreserved/decolonizing-the-classroom-is-there-space-for-indigenous-knowledge-in-academia-1.4544984/the-politics-of-citation-is-the-peer-review-process-biased-against-indigenous-academics-1.4547468

Rivers, Molly. 2021. “Waking Up to the Politics of Citation.” CLEAR (blog). June 10. https://civiclaboratory.nl/2021/06/10/waking-up-to-the-politics-of-citation/.

Saldaña-Portillo, Josefina. 2001. “Who’s the Indian in Aztlan? Re-Writing Mestizaje, Indianism, and Chicanismo from the Lacandon.” In The Latin American Subaltern Studies Reader, edited by Ileana Rodriguez. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822380771-020.

Shepherd, KJ. 2018. “‘Categories Aren’t These Things That Are Just There’: An Interview with the CLEAR Lab’s Queer Science Reading Group.” Lady Science (blog). July 16. https://www.ladyscience.com/ideas/categories-arent-these-things-that-are-just-there.

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. 2021. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. 3rd ed. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Souleles, Daniel. 2020. “What to Do with the Predator in Your Bibliography.” Allegra Lab Anthropology for Radical Optimism. https://allegralaboratory.net/what-to-do-with-the-predator-in-your-bibliography/.

Star, Susan Leigh. 1990. “Power, Technology and the Phenomenology of Conventions: On Being Allergic to Onions.” The Sociological Review 38 (1_suppl): 26–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.1990.tb03347.x.

TallBear, Kim. 2017. “Standing with and Speaking as Faith: A Feminist-Indigenous Approach to Inquiry.” In Sources and Methods in Indigenous Studies, edited by Chris Andersen and Jean M. O’Brien. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315528854.

Tierney, Matt. 2020. “Dispossessed Citation and Mutual Aid.” Diacritics 48 (3): 94–115. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/dia.2020.0021.

Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. 2012. “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1 (1): 1–40. https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/18630.

Tuck, Eve, K. Wayne Yang, and Rubén Gaztambide-Fernández. 2015. “Citation Practices Challenge.” Critical Ethnic Studies (blog). https://web.archive.org/web/20250831192817/http://www.criticalethnicstudiesjournal.org/citation-practices/.

Usher, Nikki. 2018. “Should We Still Cite the Scholarship of Serial Harassers and Sexists?” The Chronicle of Higher Education, September 7. https://www.chronicle.com/article/should-we-still-cite-the-scholarship-of-serial-harassers-and-sexists/.

Wang, Xinyi, Jordan D. Dworkin, Dale Zhou, Jennifer Stiso, Erika B. Falk, Dani S. Bassett, Perry Zurn, and David Martin Lydon-Staley. 2021. “Gendered Citation Practices in the Field of Communication.” Annals of the International Communication Association 45 (2): 134–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2021.1960180.

Zahara, Alex. 2024. “Settler Fire Management: An Examination of Wildfire Policy, Practice, and Research in the Boreal Forest Region of Northern Saskatchewan.” PhD Thesis, Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador. https://memorial.scholaris.ca/items/25adb715-47bf-4993-9d1d-47bcb0148341.