COMMENTARY

Towards Citation Justice: Ensuring an Inclusive Search and Literature Retrieval: A Western Librarian's Perspective

Floor Agnes Andrea Ruiter

Maastricht University Library, Maastricht University

Abstract

The main sources of citation injustice are the collective biases in the scientific community, including literature retrieval bias, which has direct effects on citation inequality. In this commentary I focus on index bias in literature databases, inherent/unconscious bias during search strategy development, and systematic bias of controlled vocabularies. Exemplar literature search strategies and/or retrieval analyses comparing Web of Science and OpenAlex are used to demonstrate these biases. Moreover, this commentary offers steps to consider during literature search preparation, search query building, and the search itself, which can lead to a more inclusive representation of the literature in the topic of interest and reduce citation inequity.

Keywords: inclusive literature retrieval; search strategy bias; citation inequity; systematic bias

How to cite this article: Ruiter, Floor Agnes Andrea. 2026. Towards Citation Justice: Ensuring an Inclusive Search and Literature Retrieval: A Western Librarian’s Perspective. KULA: Knowledge Creation, Dissemination, and Preservation Studies 9(1). https://doi.org/10.18357/kula.311

Submitted: 27 March 2025 Accepted: 17 July 2025 Published: 19 January 2026

Competing interests and funding: The author declares that she has no competing interests.

Copyright: © 2026 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Introduction

Current scientific literature is predominantly written and cited by and for Western scholars, resulting in underrepresentation of scholars from non-Western contexts. This inequity makes it challenging for researchers to find non-Western literature. Many factors play a role in the dominance of Western literature, including citation inequity (Chatterjee and Werner 2021; Freelon et al. 2023) and citation chaining/chaser practices. However, one indirect bias has been mainly overlooked: the lack of access to non-Western literature and systemic bias in search platforms and search strategies for literature retrieval (Weeks and Johnson 2024). What one cannot find or search for, one cannot cite!

University libraries play an important role in where researchers can find their literature. For example, researchers search for their literature in databases licensed by the university library or well-known freely accessible databases, such as PubMed. As a librarian, I believe it is important to offer a broader selection of databases to ensure a more inclusive collection and to make researchers aware of biases when gathering literature. Reflecting on one’s own unconscious bias as well as possible systemic bias within literature searching techniques, databases, and tools can result in a more inclusive selection of literature to cite, directly reducing citation inequity. This literature-gathering bias can be broken down into three elements: (1) keyword selection inherent/unconscious bias, (2) literature database/search engine bias, and (3) systematic bias of controlled vocabulary terms. This commentary will focus on systematic search practices, excluding literature retrieval by citation chaining/chasing practices, which enforces a different level of citation inequity.

1. Unconscious Bias in Keyword Selection for Search Strategies

Search strategies influence to a great extent what literature is found. For example, when interested in research about Indigenous populations around the world and their likelihood of developing dementia, the following search strategy could be employed to find relevant papers: “Indigenous” AND “dementia.” This search generates 298 results in Web of Science (on June 25, 2025) when searching in the Topic Search field only. However, the question is whether the keyword Indigenous truly captures such a wide and varied breadth of peoples globally. Terms such as Indigenous, First Nations, Native, and Aboriginal are not used interchangeably around the world and often have fluctuating meanings depending on location and context. Using generic terminology also raises concerns about who gets included or excluded in search results, as the terminology guide created by Narragunnawali (a program by Reconciliation Australia) outlines. Table 1 presents an example of the impact on literature results when searching for only one broad term versus a longer search query taking into account some more specific names of Indigenous Peoples. Where a broad query with a single term yielded 298 results, a more specific query with many terms resulted in 592.

| Database: Web of Science | |

| Date: 25-06-2025 | |

| Search query | Nr. results |

| TS=(“indigenous”) AND TS=(“dementia”) | 298 |

| TS=(“indigenous” OR “first-nation*” OR “aborigin*” OR “torres strait*” OR “maori*” OR “metis” OR “sami” OR “american indian*” OR “inuk” OR “inuit” OR “tribe*”) AND TS=(“dementia”)1 | 592 |

Many tools and practices exist to enhance search terms: (AI-driven) text-mining tools (Grames et al. 2019; Kugley et al. 2017; O’Keefe et al. 2023), translation of search terms into other languages (Pieper and Puljak 2021; Stern and Kleijnen 2020), and databases’ controlled vocabularies. However, all these methods bring their own bias. For example, Glickman and Sharot (2025) observed an amplification of human bias when using AI-driven methods. Moreover, the data used for text mining can contain systematic bias due to overrepresentation of Western literature within the dataset used (Hovy and Prabhumoye 2021). Although translation practices to other languages can increase inclusivity (Pieper and Puljak 2021), researchers should always stay aware of possible linguistic bias within the languages of choice (Beukeboom 2014). Bias within controlled vocabularies will be further discussed in the third section of this commentary.

2. Bias in Literature Databases and Search Engines

2.1 Academic Literature Databases

Literature databases are the gold standard in finding literature. However, many of these databases select journals to be indexed in their database based on strict criteria, which results in systematic inequity (Tennant 2020). For example, the multidisciplinary database Web of Science (WoS) is widely used. However, WoS indexes based on the impact factor of journals, which is directly linked to citation injustice practices. Scopus, another multidisciplinary database, has been reported to offer wider coverage in both disciplines and document types, as well as a better representation of non-English literature compared to WoS (Pranckutė 2021). Nevertheless, both WoS and Scopus only include journal articles with an abstract written in English, which results in predominantly Western-focused and English-language literature (Scopus 2025; WoS 2025). An alternative to these commercial Western-based databases, as stated above, is OpenAlex (Priem et al. 2022). This open-access database has fewer limits on their indexing criteria and has no language requirement, thus allowing for a more equitable representation of scientific output (Céspedes et al. 2025). Moreover, OpenAlex has been observed to cover a higher percentage of diamond and gold open access (OA) journals compared to WoS and Scopus (Simard et al. 2025).

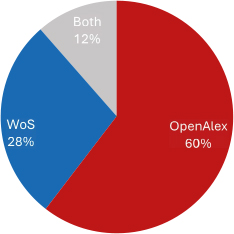

When comparing the results of the search in WoS as presented in Table 1 with the more inclusive database OpenAlex (Table 2), the latter search yielded a substantially higher number of papers (1,217 in OpenAlex versus 592 in WoS). When combining all results from both databases and deduplicating, 205 duplicates were found within OpenAlex’s and WoS’s own datasets (183 and 22 for OpenAlex and WoS, respectively), mainly due to preprint versions or differences/typos in DOIs. I identified 1,439 unique studies, of which 165 unique titles were found in both databases (12 percent), with 405 unique results from WoS (28 percent) and 869 unique results from OpenAlex (60 percent) (Table 3; Figure 1).

| OpenAlex (duplicates) | WoS (duplicates) | Total (duplicates) | |

| Unique titles | 869 (183) | 405 (22) | 1,274 (205) |

| Unique titles found in both | 165 | 165 | 165 (165) |

| 1,034 | 570 | 1,439 (370) |

Figure 1. Percentage of studies found in both WoS and OpenAlex (grey), or only in WoS (blue) or OpenAlex (red).

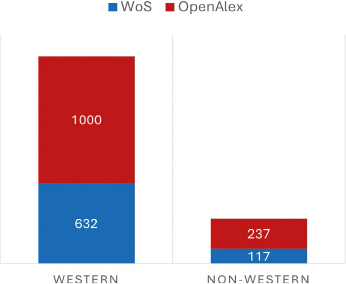

Moreover, when exporting the author affiliation countries for all authors, I found 15 more affiliation countries in the OpenAlex results compared to the WoS results, 70 versus 55 countries, respectively (see Appendices A and B). Affiliations of the same country within the author list of one article were counted as one, while each individual country was counted separately, disregarding author positions. Affiliation countries were categorized as non-Western or Western countries (see “Affiliation Countries” in the Methods section). This resulted in 237 articles with authors of non-Western countries (48 countries) found in OpenAlex compared to only 117 articles (38 countries) in WoS (Figure 2), indicative of the broader geographic scope of the database OpenAlex.

Figure 2. Number of author affiliations from Western or non-Western countries found in the searches described in Tables 1 and 2 for the databases WoS (blue) and OpenAlex (red).

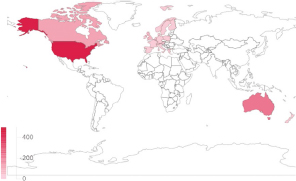

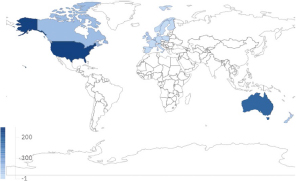

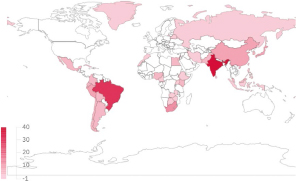

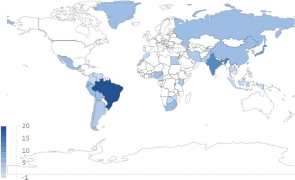

A visual representation of the geographic spread (Western or non-Western) between the two databases can be found in Figures 3 to 6. Certain differences remained, however: OpenAlex did not find articles of 6 country affiliations that were found in WoS (all non-Western countries; see Appendices A and B), and WoS did not find articles of authors of 21 country affiliations (16 non-Western affiliations; see Appendices A and B) that were found in OpenAlex (Appendices A and B). These differences have been observed before. Maddi et al. (2025) observed a more inclusive indexing of OA journals in OpenAlex when they compared it to WoS and Scopus; however, they also observed an underrepresentation of certain regions and (emerging) countries in OpenAlex compared to WoS and Scopus. Therefore, it is recommended in evidence-based practices to always use a variation of databases for an inclusive literature search. Moreover, multilingual or regionally focused databases can be a source for additional non-Western literature. Examples include the databases Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO) (Didier 2025), which indexes articles published in journals from countries within the SciELO network; Latin America and the Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS), which indexes articles in journals published in Latin America and the Caribbean; African Journals Online (AJOL) (Alonso-Álvarez 2025), which indexes articles in journals published in Africa; and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), which indexes articles in journals published in China.

Figure 3. Geographic distribution of Western country affiliations in search results from OpenAlex. Image generated via the free version of Draxlr.

Figure 4. Geographic distribution of Western country affiliations in search results from WoS. Image generated via the free version of Draxlr.

Figure 5. Geographic distribution of non-Western country affiliations in search results from OpenAlex. Image generated via the free version of Draxlr.

Figure 6. Geographic distribution of non-Western country affiliations in search results from WoS. Image generated via the free version of Draxlr.

2.2 Search Engines

Search engines are a key source for non-academic or grey literature resources. Grey literature refers to any document that has not been through peer review (e.g., preprints, policy, poetry, songs, etc.). Grey literature has been associated with reducing literature bias in systematic reviews (Paez 2017). However, when searching for grey literature in search engines, bias occurs due to biased queries (Kacperski et al. 2024), underlying algorithms (Peterson‐Salahuddin 2024; Udoh et al. 2024; Wijnhoven and van Haren 2021), personal preferences (Lin et al. 2023), and commercial/political advertisements (Epstein and Robertson 2015). Google is a well-known example of human- and algorithm-based bias (Lin et al. 2023), which makes finding representative grey literature a challenging task. However, Google’s search operators can help mitigate this bias. For example, with the search operator site: it is possible to filter results to a country of interest. For example, site:.br “Indigenous” AND “dementia” will search for any literature on dementia and Indigenous populations in only Brazilian-based websites.

Besides search engines, grey literature databases also exist. However, it is mostly unclear if bias occurs in these databases as index criteria are not clearly defined. Overton Index is an example of a database that shares a similar goal of reducing inequity and underrepresentation. This database tries to reduce literature bias by indexing any policy or guideline documents openly available on the web and making them easily searchable (Holvey 2025).

3. Possible Systematic Bias in Controlled Vocabulary

Besides free-text terms, many databases use controlled vocabularies/subject headings to index articles in the collection to one specified term. Although these terms organize literature, they have been criticized for re-enforcing colonial and systemic biases (Howard and Knowlton 2018; Moura 2024). In addition, there is a lack of accountability and transparency about how minority definitions are determined (Harding et al. 2021). Assigned terms were found to poorly reflect the actual work (Amar-Zifkin et al. 2025; Bullard et al. 2022) and differ from the terminology used by information seekers and cultures themselves (Holstrom 2021). Moreover, the terms themselves do not adapt to language and cultural changes in a timely fashion (Drabinski 2013; Hadfield 2020). For example, despite the replacement of the terms blacks and negro in everyday vocabulary, these terms were only replaced in 2022 as Medical Subject Headings (MeSH, mainly used in the databases PubMed/Medline) after medical librarians reached out with an open letter to the MeSH committee to urgently reconsider and change these terms (MLA 2022). This has led to a much larger revision of MeSH terminology to be more inclusive, with terms such as black people and transgender persons introduced in 2023 and 2024. When searching in a literature database with subject headings, ensuring the controlled vocabulary accurately represents the concept needs to be considered. Moreover, it is always recommended to search both controlled vocabulary and free-text terms to ensure a sensitive search (McGowan et al. 2016).

Steps for Identifying Unconscious or Inherent Bias During Literature Retrieval

Using critical thinking and considering inclusivity are as important when conducting a literature search as they are in other steps of the research cycle (Gültzow et al. 2023; Jaeger-McEnroe 2025; Yunkaporta and Moodie 2021).

Before starting a search, scholars should consider their own positionality and privileges to uncover potential inherent/unconscious bias (Martin and Mirraboopa 2003; Vong 2021). As Tynan and Bishop (2022, 506) state: “A relational literature review process does not necessarily start with literature: it begins with your own relationships to people, places, and knowledge. A relational literature review process shifts the purpose of a literature review, not to extract data, establish a territory or find the gaps, but as an obligation to extend your relations, and therefore your work, for future generations.” Identifying individual bias is the first step to ensuring an inclusive literature retrieval. For researchers, this may include extending their network to familiarize themselves with different perspectives and collaborate with or learn from the work of focus groups/geographic locations before retrieving literature (Tynan and Bishop 2022).

The following example may illustrate inherent bias in defining search terms. Mia (hypothetical character) is a researcher at an EU university. She is a white, bisexual, cisgender female, and her family has been living in the EU for many generations. In her research, she is interested in Indigenous populations around the world and their conceptions of sexuality and gender identity.

She developed the following search strategy:

(“Indigenous” OR “first-nation*” OR “aborigin*” OR “torres strait*” OR “maori*” OR “metis” OR “sami” OR “american indian*” OR “inuk” OR “inuit” OR “tribe*”)

AND

(“lesbian*” OR “lesbigay” OR “gay” OR “gays” OR “homosex*” OR “homophil*” OR “bisex*” OR “same sex” OR “samesex” OR “same-sex” OR “sexual minorit*” OR “sexual orientation*” OR “non-heterosex*” OR “nonheterosex*” OR “LGB” OR “MSM” OR “men-having-sex-with-men” OR “men-who-have-sex-with-men” OR “men-who-have-sex-with-other-men” OR “women-who-have-sex-with-women” OR “WSW” OR “lgbt*” OR “lgbbtq*” OR “GLBT” OR “queer*” OR “pansex*” OR “intersex*” OR “asex” OR “sexual-dissiden*” OR “gender dysphoria” OR “nonbinair*” OR “nonbinar*” OR “non-binair*” OR “non-binar*” OR “transgender” OR “agender” OR “polysex*” OR “gender fluid” OR “gender-nonconform*” OR “gender divers*”)

Focusing on the Indigenous concept first, the specific terminology used here are descriptors for Indigenous populations based in Western countries (see Table 4), although the geographic limitations thereof are partially offset by the broader terms “tribe*” and “first-nation*.” This search may still exclude unrepresented Indigenous populations such as the Indigenous tribes of Taiwan (e.g., Amis, Atayal, Paiwan), the Maya Peoples in Guatemala, or the Aymaras People in Bolivia. Moreover, when looking at concepts of sexuality and gender identity, all the descriptors used in the search were Western terminology; many other cultures, including Indigenous cultures, have their own terminology for sexuality and gender identity, including Two-Spirit (Indigenous Peoples in North America) or Acaults (Myanmar) (Mehta et al. n.d.).

Although Mia is interested in all Indigenous populations, her choice of terminology is very Western focused, which is not surprising due to her Western positioning. This is why it is of the utmost importance for scholars to critically assess their individual inherent bias in a topic of study as it may potentially lead to exclusion of relevant population groups and/or papers. While Mia is part of the LGBTQ+ community, one could argue whether she is in a position to write about Indigenous knowledge within this topic because of her Western origin (Chilisa 2020). She should extend her network to include Indigenous people so that she can learn from or collaborate with them to determine respectful and accurate search terminology.

Summary and Recommendations

As outlined in this paper, systematic and inherent/unconscious bias in literature searches may lead to the exclusion of relevant papers, which may then result in misrepresentation. This can be addressed by first identifying all possible terms used by or within the target population/concept and entering them in separate searches. If these do not yield results, this may indicate a possible limitation of the search or hidden/silenced/underrepresented knowledge in the topic, which can be mitigated by actively seeking representation of the target population in defining search terms. Further, it is key to document all search terms and final search strategy in the methodology or supplementary information to offer transparency on choices made and potential limitations thereof (Harding et al. 2021), which can be inspiration for other researchers in the future. Additionally, I recommend using all possible terminology when searching for grey literature. Searching literature outside of the academic scope may also aid in finding hidden knowledge, as does asking experts in the target group themselves. These steps combined will result in representative literature inclusion and reduce inherent or systematic bias due to political or cultural constructs, which subsequently will reduce possible unconscious citation inequity in scholars’ work and in time the citation inequity in the different disciplinary fields.

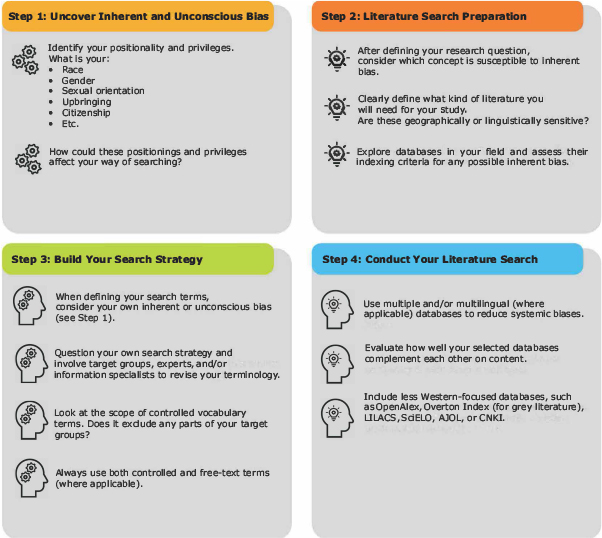

In summary, here is a recommended step-by-step process for researchers to ensure an inclusive literature retrieval (Figure 7):

Figure 7. Key steps and considerations when preparing and conducting a literature search to ensure a more inclusive literature retrieval.

Step 1: Uncover Inherent and Unconscious Bias

- Identify your positionality and privileges. What is your:

- Race

- Gender

- Sexual orientation

- Upbringing

- Citizenship

- Etc.

- How could these positionings and privileges affect your way of searching?

Step 2: Literature Search Preparation

- After defining your research question, consider which concept is susceptible to inherent bias.

- Clearly define what kind of literature you will need for your study. Are these geographically or linguistically sensitive?

- Explore databases in your field and assess their indexing criteria for any possible inherent bias.

Step 3: Build Your Search Strategy

- When defining your search terms, consider your own inherent or unconscious bias (see Step 1).

- Question your own search strategy and involve target groups, experts, and/or information specialists to revise your terminology.

- Look at the scope of controlled vocabulary terms. Does it exclude any parts of your target groups?

- Always use both controlled and free-text terms (where applicable).

Step 4: Conduct Your Literature Search

- Use multiple and/or multilingual (where applicable) databases to reduce systemic biases.

- Evaluate how well your selected databases complement each other on content.

- Include less Western-focused databases, such as OpenAlex, Overton Index (for grey literature), LILACS, SciELO, AJOL, or CNKI.

Methods

Literature Deduplication

Results from the searches presented in Tables 1 and 2 were exported to Excel (Microsoft 365) directly or via application programming interface (API), WoS and OpenAlex respectively. Articles were deduplicated by hand, due to error in result export from OpenAlex to a ris-file. A number of duplicates and unique articles for WoS and OpenAlex were identified after deduplication of duplicates within the databases themselves.

Affiliation Countries

Countries of author affiliations were exported to Excel (Microsoft 365) from WoS and OpenAlex (via API) and combined into one Excel file. Countries were classified as Western or non-Western via the following classification:

Western countries are: EU, Andorra, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Monaco, Norway, San Marino, Switzerland, United Kingdom, Vatican State, USA, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

Non-Western countries are: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Belarus, Yugoslavia, Kosovo, Macedonia, Moldova, Montenegro, Russia, Serbia, Turkey, Ukraine, all countries in Africa, all countries in South and Central America, all countries in Asia, and all countries in Oceania (except Australia and New Zealand).

A pivot was generated to calculate the number of Western versus non-Western countries of affiliation per database and the corresponding number of articles per author affiliation country. Data can be found in Appendices A and B.

Figures and Graphs

Graphs were made via Excel (Microsoft 365), and world map distribution images in Figures 3 to 6 were generated via the free version of Draxlr. Figure 7 was made in Adobe Illustrator 2025.

Literature Search

Searches to obtain literature for the commentary (not to be confused with the examplar searches within the main text) were conducted in WoS, Library, Information Science & technology Abstracts (EBSCO), and OpenAlex. Full information on search queries can be found in Appendices C to E. Relevant articles were identified via manual title-abstract and full-text screening.

Positionality

I am a scientific information specialist at an EU-based university. This gives me the privilege of being able to search and access highly expensive licensed databases/journals, and I recognize this gives me an advantage over others. I am not an expert on Indigenous knowledges and only used this as an example. If you are interested in searches on Indigenous topics, I highly recommend collaborating with Indigenous Peoples themselves. I have written this piece in the Western perspective of literature retrieval practices and realize the mismatch of this work with other literature retrieval practices outside of the Western academic evidence-based practice. This piece is written to challenge Western readers to think outside their own perspective, which can also differ from my own.

Dedication

This work is dedicated to Heleen “troj” van Nieuwland, who encourages me to keep reading and writing even though my dyslexia made it harder to keep up with the rest, who raised me to be creative and to always challenge the status quo. This inspired me to think that one step further outside the box.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Anja Krumeich and Gonnie Klabbers for introducing me to this field of inclusive literature during our decolonization project for the MSc Global Health. Moreover, I would like to thank Marieke Schor and Gonnie Klabbers for their constructive and critical feedback on the manuscript and Ivo Bleijlevens for exporting and formatting data from OpenAlex via API.

Appendices

| Database: OpenAlex | ||

| Date: 11-03-2025 | ||

| Query number | Search query | Nr. results |

| 1 | openalex.org/works?filter=title_and_abstract.search:inequity|inequite|underrepresentation|underrepresentative|underrepresenting|bias|injustices | 1,274,000 |

| 2 | openalex.org/works?filter=title_and_abstract.search:literature|information|resources,title_and_abstract.search:gathering|retrieving|retrieval|searches|searching|databases|search+tools|search+engines | 1,959,000 |

| 3 | openalex.org/works?filter=title_and_abstract.search:inequity|inequite|underrepresentation|underrepresentative|underrepresenting |bias|injustices,title_and_abstract.search:literature|information|resources,title_and_abstract. search:gathering|retrieving|retrieval|searches|searching|databases|search+tools|search+engines | 65,220 |

| 4 | openalex.org/works?filter=title_and_abstract.search:inequity|inequite|underrepresentation|underrepresentatitive|underrepresenting |bias|injustices,title_and_abstract.search:literature|information|resources,title_and_abstract. search:gathering|retrieving|retrieval|searches|searching|databases|search+tools|search+engines,type:types/preprint|article,publication_year:2020-2025 | 14,780 |

References

Alonso-Álvarez, Patricia. 2025. “A Small Step Towards the Epistemic Decentralization of Science: A Dataset of Journals and Publications Indexed in African Journals Online.” Journal of Data and Information Science. https://doi.org/10.2478/jdis-2025-0034.

Amar-Zifkin, Alexandre, Taline Ekmekjian, Virginie Paquet, and Tara Landry. 2025. “Algorithmic Indexing in MEDLINE Frequently Overlooks Important Concepts and May Compromise Literature Search Results.” Journal of the Medical Library Association 113 (1): 39–48. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2025.1936.

Beukeboom, Camiel J. 2014. “Mechanisms of Linguistic Bias: How Words Reflect and Maintain Stereotypic Expectancies.” In Social Cognition and Communication, edited by Joseph P. Forgas, Orsolya Vincze, and János László. Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203744628.

Bullard, Julia, Brian Watson, and Caitlin Purdome. 2022. “Misrepresentation in the Surrogate: Author Critiques of ‘Indians of North America’ Subject Headings.” Cataloging & Classification Quarterly 60 (6–7): 599–619. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639374.2022.2090039.

Céspedes, Lucía, Diego Kozlowski, Carolina Pradier, Maxime Holmberg Sainte-Marie, Natsumi Solange Shokida, Pierre Benz, Constance Poitras, Anton Boudreau Ninkov, Saeideh Ebrahimy, Philips Ayeni, Sarra Filali, Bing Li, and Vincent Larivière. 2025. “Evaluating the Linguistic Coverage of OpenAlex: An Assessment of Metadata Accuracy and Completeness.” Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 76 (6): 884–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24979.

Chatterjee, Paula, and Rachel M. Werner. 2021. “Gender Disparity in Citations in High-Impact Journal Articles.” JAMA Network Open 4 (7): e2114509. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.14509.

Chilisa, Bagele. 2020. Indigenous Research Methodologies. 2nd ed. Sage. https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/indigenous-research-methodologies/book241776#description.

Didier, Nicolas. 2025. “Decolonizing Public Administration in Latin America: A Systematic Literature Review of Trending Discussions in the Region.” Public Administration and Development: 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.2092.

Drabinski, Emily. 2013. “Queering the Catalog: Queer Theory and the Politics of Correction.” The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy 83 (2): 94–111. https://doi.org/10.1086/669547.

Epstein, Robert, and Ronald E. Robertson. 2015. “The Search Engine Manipulation Effect (SEME) and Its Possible Impact on the Outcomes of Elections.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112 (33): E4512–E4521. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1419828112.

Freelon, Deen, Meredith L. Pruden, Kirsten A. Eddy, and Rachel Kuo. 2023. “Inequities of Race, Place, and Gender Among the Communication Citation Elite, 2000–2019.” Journal of Communication 73 (4): 356–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqad002.

Glickman, Moshe, and Tali Sharot. 2025. “How Human–AI Feedback Loops Alter Human Perceptual, Emotional and Social Judgements.” Nature Human Behaviour 9 (2): 345–59. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-02077-2.

Grames, Eliza M., Andrew N. Stillman, Morgan W. Tingley, and Chris S. Elphick. 2019. “An Automated Approach to Identifying Search Terms for Systematic Reviews Using Keyword Co-Occurrence Networks.” Methods in Ecology and Evolution 10 (10): 1645–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13268.

Gültzow, Thomas, Efrat Neter, and Hanne M. L. Zimmermann. 2023. “Making Research Look Like the World Looks: Introducing the ‘Inclusivity & Diversity Add-On for Preregistration Forms’ Developed During an EHPS2022 Pre-Conference Workshop.” The European Health Psychologist 22 (6), 1063–69. https://ehps.net/ehp/index.php/contents/article/view/3436/.

Hadfield, Ruth M. 2020. “Delay and Bias in PubMed Medical Subject Heading (MeSH®) Indexing of Respiratory Journals.” Preprint, medRxiv, October 4. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.01.20205476.

Harding, Louise, Caterina J. Marra, and Judy Illes. 2021. “Establishing a Comprehensive Search Strategy for Indigenous Health Literature Reviews.” Systematic Reviews 10 (1): 115. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01664-y.

Holstrom, Chris. 2021. “The Sears List of Subject Headings: Social and Cultural Dimensions in Historical, Theoretical, and Design Contexts.” Proceedings from North American Symposium on Knowledge Organization 8: 1–11. https://doi.org/10.7152/nasko.v8i1.15865.

Holvey, Kate. 2025. “How Maastricht Is Advocating for Inclusive Research and Decolonisation.” Overton (blog). https://www.overton.io/blog/how-maastricht-is-advocating-for-inclusive-research-and-decolonisation. Archived at: https://perma.cc/G58V-ZAJ8.

Hovy, Dirk, and Shrimai Prabhumoye. 2021. “Five Sources of Bias in Natural Language Processing.” Language and Linguistics Compass 15 (8): e12432. https://doi.org/10.1111/lnc3.12432.

Howard, Sara A., and Steven A. Knowlton. 2018. “Browsing Through Bias: The Library of Congress Classification and Subject Headings for African American Studies and LGBTQIA Studies.” Library Trends 67 (1): 74–88. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2018.0026.

Jaeger-McEnroe, Emily. 2025. “Rethinking Authority and Bias: Modifying the CRAAP Test to Promote Critical Thinking about Marginalized Information.” College & Research Libraries News 86 (1): 12–17. https://doi.org/10.5860/crln.86.1.12.

Kacperski, Celina, Mona Bielig, Mykola Makhortykh, Maryna Sydorova, and Roberto Ulloa. 2024. “Examining Bias Perpetuation in Academic Search Engines: An Algorithm Audit of Google and Semantic Scholar.” First Monday 29 (11). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v29i11.13730.

Kugley, Shannon, Anne Wade, James Thomas, Quenby Mahood, Anne-Marie Klint Jørgensen, Karianne Hammerstrøm, and Nila Sathe. 2017. “Searching for Studies: A Guide to Information Retrieval for Campbell Systematic Reviews.” Campbell Systematic Reviews 13 (1): 1–73. https://doi.org/10.4073/cmg.2016.1.

Lin, Cong, Yuxin Gao, Na Ta, Kaiyu Li, and Hongyao Fu. 2023. “Trapped in the Search Box: An Examination of Algorithmic Bias in Search Engine Autocomplete Predictions.” Telematics and Informatics 85: 102068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2023.102068.

Maddi, Abdelghani, Marion Maisonobe, and Chérifa Boukacem-Zeghmouri. 2025. “Geographical and Disciplinary Coverage of Open Access Journals: OpenAlex, Scopus, and WoS.” PLOS ONE 20 (4): e0320347. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0320347.

Martin-Booran Mirraboopa, Karen. 2003. “Ways of Knowing, Being and Doing: A Theoretical Framework and Methods for Indigenous and Indigenist Re-search.” Journal of Australian Studies 27 (76): 203–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/14443050309387838.

McGowan, Jessie, Margaret Sampson, Douglas M. Salzwedel, Elise Cogo, Vicki Foerster, and Carol Lefebvre. 2016. “PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 75: 40–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021.

Medical Library Association. 2022. “Open Letter to NLM Regarding MeSH Term Changes.” Medical Library Association. https://www.mlanet.org/article/open-letter-to-nlm-regarding-mesh-term-changes/. Archived at: https://perma.cc/9K6F-CY8A.

Mehta, Noor, Rhiannon Callahan, Rachel Greenberg, Kaitlin Kerr, Miranda Melson, K. J. Rawson, Cailin Roles, Eamon Schlotterback, and Cecilia Wolfe. n.d. “Global Terms.” Digital Transgender Archive. https://www.digitaltransgenderarchive.net/learn/terms. Archived at: https://perma.cc/2FB3-MN5R.

Moura, Maria Aparecida. 2024. “Information and Code Biases: Social Differentiation, Intersectionality and Decoloniality in Knowledge Organization Systems.” Knowledge Organization 51 (7): 514–20. https://doi.org/10.5771/0943-7444-2024-7-514.

Narragunnawali: Reconciliation in Education. n.d. “Terminology Guide: A Guide to Using Respectful and Inclusive Language and Terminology.” https://www.narragunnawali.org.au/about/terminology-guide.

O’Keefe, Hannah, Judith Rankin, Sheila A. Wallace, and Fiona Beyer. 2023. “Investigation of Text-Mining Methodologies to Aid the Construction of Search Strategies in Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy—A Case Study.” Research Synthesis Methods 14 (1): 79–98. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1593.

Overton. 2025. “Guide: How to Use Overton to Decolonise Your Research and Teaching.” Overton.io. https://www.overton.io/how-to-use-overton-to-decolonise-your-research-and-teaching. Archived at: https://perma.cc/C6LX-4P6G.

Paez, Arsenio. 2017. “Gray Literature: An Important Resource in Systematic Reviews.” Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine 10 (3): 233–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/jebm.12266.

Peterson‐Salahuddin, Chelsea. 2024. “From Information Access to Production: New Perspectives on Addressing Information Inequity in Our Digital Information Ecosystem.” Journal of the Association for Information Science & Technology 75 (10): 1134–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24879.

Pieper, Dawid, and Livia Puljak. 2021. “Language Restrictions in Systematic Reviews Should Not Be Imposed in the Search Strategy but in the Eligibility Criteria if Necessary.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 132:146–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.12.027.

Pranckutė, Raminta. 2021. “Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The Titans of Bibliographic Information in Today’s Academic World.” Publications 9 (1): 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications9010012.

Priem, Jason, Heather Piwowar, and Richard Orr. 2022. “OpenAlex: A Fully-Open Index of Scholarly Works, Authors, Venues, Institutions, and Concepts.” Preprint, v2, arXiv, June 17. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2205.01833.

Scopus 2025. “Content Policy and Selection” Elsevier. https://www.elsevier.com/products/scopus/content/content-policy-and-selection.

Simard, Marc-André, Isabel Basson, Madelaine Hare, Vincent Larivière, and Philippe Mongeon. 2025. “Examining the Geographic and Linguistic Coverage of Gold and Diamond Open Access Journals in OpenAlex, Scopus, and Web of Science.” Quantitative Science Studies 6: 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1162/QSS.a.1.

Stern, Cindy, and Jos Kleijnen. 2020. “Language Bias in Systematic Reviews: You Only Get Out What You Put in.” JBI Evidence Synthesis 18 (9): 1818–19. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBIES-20-00361.

Tennant, Jonathan P. 2020. “Web of Science and Scopus Are Not Global Databases of Knowledge.” European Science Editing 46: e51987. https://doi.org/10.3897/ese.2020.e51987.

Tynan, Lauren, and Michelle Bishop. 2022. “Decolonizing the Literature Review: A Relational Approach.” Qualitative Inquiry 29 (3–4): 498–508. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778004221101594.

Udoh, Emmanuel Sebastian, Xiaojun Yuan, and Abebe Rorissa. 2024. “A Framework for Defining Algorithmic Fairness in the Context of Information Access.” Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology 61 (1): 667–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.1077.

Vong, Silvia. 2021. “From Dispositions to Positionality: Addressing Dispositions of the Student Researcher in the ACRL Framework.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 47 (6): 102457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2021.102457.

Weeks, Thomas C., and Melissa E. Johnson. 2024. “Using Positionality to Address Student Bias in Information Seeking.” Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology 61 (1): 1126–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.1206.

Wijnhoven, Fons, and Jeanna van Haren. 2021. “Search Engine Gender Bias.” Frontiers in Big Data 4: 622106. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdata.2021.622106.

WoS 2025. “Journal Evaluation Process and Selection Criteria.” Clarivate. https://clarivate.com/academia-government/scientific-and-academic-research/research-discovery-and-referencing/web-of-science/web-of-science-core-collection/editorial-selection-process/journal-evaluation-process-selection-criteria/.

Yunkaporta, Tyson, and Donna Moodie. 2021. “Thought Ritual: An Indigenous Data Analysis Method for Research.” In Indigenous Knowledges: Privileging Our Voices, edited by Tarquam McKenna, Donna Moodie, and Pat Onesta. Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004461642_006.

Footnotes

1 These search queries are merely examples, and more terms could be added to surface more results. I recommend involving experts such as information specialists/librarians, researchers in the field, and target groups in refining these terms.

2 Due to limited advanced search possibilities, I used a revised version of the search.