Counting, Carrying, Crafting: Mapping Citations Otherwise

Maud Oostindie

Maastricht University

Veerle Spronck

HKU University of the Arts Utrecht*

* The authors are named in alphabetical order, and have each contributed equally to this publication

Abstract

This multimedia exchange explores the politics of citation beyond traditional academic formats, engaging with issues of citational justice through text, drawings, collages, maps, and knitted data visualisations. Through an email correspondence, we reflect on the tensions between quantification and the lived, relational nature of scholarly influence. While citation counts and diversity metrics can reveal biases, they also risk abstracting knowledge into numbers. This article asks what it means to do justice to the people, ideas, and experiences that shape academic work.

Turning to alternative metaphors—carrying and mapping—we reconsider citation as an embodied and material practice. Carrying evokes the ways knowledge is gathered, held, and moved with over time, while mapping traces connections, highlights omissions, and navigates shifting terrains of influence. These approaches make space for sources that may not fit conventional reference lists: fleeting conversations, students’ insights, artistic works, or moments of observation.

Through text, image, and craft, we explore a citational practice that embraces complexity and multiplicity. Ultimately, we propose an expanded citational practice that acknowledges a wider range of influences and explores how other formats might better accommodate these forms of knowledge. The exchange results in a “reference map” in which we experiment with an alternative strategy for citation.

Keywords: citational justice; academic knowledge practices; mapping; multimedia exchange; artistic research

How to cite this article: Oostindie, Maud, and Veerle Spronck. 2026. Counting, Carrying, Crafting: Mapping Citations Otherwise. KULA: Knowledge Creation, Dissemination, and Preservation Studies 9(1). https://doi.org/10.18357/kula.306

Submitted: 24 March 2025 Accepted: 17 July 2025 Published: 19 January 2026

Competing interests and funding: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Copyright: © 2026 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

– □ ×

From: Maud <m.oostindie@maastrichtuniversity.nl>; Veerle <veerle.spronck@hku.nl>

To: Reader <reader@kulajournal.ca>

Sent: Wednesday, July 2, 2025, 01:22 PM

Dear Reader,

What you’re about to read is a real-time exchange between the two of us, sparked by the call for this special issue. Later, the exchange was lightly edited for clarity, and to fit with the journal’s house style. Since what follows does not take the shape of a traditional academic article, we wanted to offer a few words of orientation. We started out with a loose idea of the format for this exchange, then let the conversation unfold—through letters, emails, and images sent back and forth over several weeks between December 2024 and February 2025.

We don’t usually email each other. Our conversations tend to take place via chat or over a coffee. And we don’t usually speak to each other in English either, but rather in Dutch (written) or local Limburgish dialect (spoken). But while both the language (English) and the medium (email) did not necessarily feel natural to us, the correspondence emerged from our shared rhythm of thinking, responding, and making together.

What you’ll find here is not a finished argument or unified voice, but a layered conversation. The visuals are part of that conversation too: The knitted images are made by Veerle, the others by Maud.

—Veerle and Maud

– □ ×

From: Maud <m.oostindie@maastrichtuniversity.nl>

To: Veerle <veerle.spronck@hku.nl>

Sent: Tuesday, December 3, 2024, 09:32 AM

Dear Veerle,

Today marks day 1,204 of doing my PhD. As I am writing this, my EndNote reference manager is filled with 1,024 references—can you believe the symmetry of these numbers?! My monograph (or should I say book, dissertation, thesis?) is slowly taking shape, but it remains a work in progress. There are numerous folders on my laptop, across which are scattered tens of Microsoft Word documents with draft chapters, notes, and discarded bits of writing, all containing some version of a reference list, citing some part of my EndNote collection.

As a proper anthropologist, interested in power dynamics (as anthropologists often are), I try to look critically at my citation practices: How many women do I cite? How many people of colour? And how many women of colour? How many scholars from a university in the Global South? Do I cite publications from large journals and publishers or from more obscure publications? How many of the works I cite are originally written in a language other than English?

How do you deal with this? I feel like there is not enough time in the day—not in the past 1,204 days, and not in the remaining ~365 days of my PhD trajectory—to do justice to all of this. It gets overwhelming, don’t you think?

—Maud

– □ ×

From: Veerle <veerle.spronck@hku.nl>

To: Maud <m.oostindie@maastrichtuniversity.nl>

Sent: Monday, December 9, 2024, 10:24 AM

Dear Maud,

Wow, 1,024 references. And how many of those are female? Not sure if I want an answer to that . . .

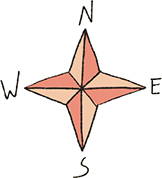

I went back to a publication (Spronck, Peters, and Van de Werff 2021) I wrote during my PhD, when, admittedly, citational justice wasn’t on my mind. I counted the gender balance in our reference list: We cited fifty-four sources written by seventy-nine authors in total. I then needed to establish the gender of the authors. Sometimes this meant looking them up online, as their names alone did not tell me. Alongside male and female, I also added an “other” category, to include non-binary authors, collectives under a single name, and institutional publications without an assigned author. Out of these seventy-nine authors, fifty-four were male, twenty-four female, and one other. That does not look good. And honestly, I am pretty sure that if I went the intersectional way you proposed, it would look even worse. As an experiment, I decided to knit a visualisation of this gender (im)balance, inspired by the “knitted web of science” that Gregory et al. (2023) presented in their chapter on interdisciplinarity and open research data. I was simply curious what it would do to see the numbers visualised, and even be able to touch them (building on Lupi and Posavec 2016, and using a knitting technique from Wormhead 2024). The result (Figure 1) was quite daunting . . .

For my own sanity, I then did the same (Figure 2) with an article I recently wrote with a colleague (Hoegen and Spronck 2025). Here, we made a conscious effort to cite in a more feminist way (see Carlier et al. 2022). The numbers of that article look better—or at least they feel better to me: fifteen references, seventeen authors, three male, thirteen female, and one other.

—Veerle

– □ ×

From: Maud <m.oostindie@maastrichtuniversity.nl>

To: Veerle <veerle.spronck@hku.nl>

Sent: Wednesday, December 11, 2024, 05:11 PM

Dear Veerle,

Hm, we do kind of fall into the trap of wanting to count when talking about citational politics and justice. Isn’t this need for quantification precisely one of the problems? In his book Trust in Numbers (1995), Theodore Porter (ironically, a white man writing from a prestigious American university . . . ) writes about the tendency to place so much importance on quantification. He writes about quantification as a “social technology” (1995, 49), where numbers are used as a stand-in for truth. While he writes about bureaucracy and decision-making, I cannot help but see the connection with the topic of our conversation—citational politics. What is it exactly that we want to do justice to in our citational practices? And does abstracting identities and counting them actually help in pursuing this?

—Maud

– □ ×

From: Veerle <veerle.spronck@hku.nl>

To: Maud <m.oostindie@maastrichtuniversity.nl>

Sent: Friday, December 13, 2024, 04:13 PM

Dear Maud,

Those knitted reference visualisations were quite some work. . . . And now it turns out that I, in your words, fell “into the trap of wanting to count.” :’)

However, I feel it might not be a trap; quantification can perhaps be a first step toward awareness about the ways in which we cite. Seeing it visualised, it is undeniable that our reference lists are not neutral. After all, by citing we are doing something: we are crafting the landscape in which we position ourselves as researchers, so we better be aware of the landscaping we do. Quantification, then, is the first step towards recognising that we have been planting the same trees over and over and over again. When we render that visible, we can begin to observe what that actually does to the landscape as a whole. From there, we can move on. But moving on is easier said than done, because of the highly routinised nature of academic practices (Knorr Cetina 1999).

As an ethnographer who spends most of her time among artists and artistic researchers, not all my sources are written—let alone peer-reviewed articles, books, or chapters that neatly fit into The Chicago Manual of Style. They are performative, material, sensory, speculative, or fleeting in other ways. I struggle to do justice to them within traditional academic formats of citation. I am curious whether you recognise this, and what “other” sources play a role in your practice.

How about we both collect five to ten references that influence(d) our work but that we usually cannot or do not cite in publications? I will start collecting tomorrow.

—Veerle

– □ ×

From: Maud <m.oostindie@maastrichtuniversity.nl>

To: Veerle <veerle.spronck@hku.nl>

Sent: Wednesday, December 18, 2024, 11:13 AM

Dear Veerle,

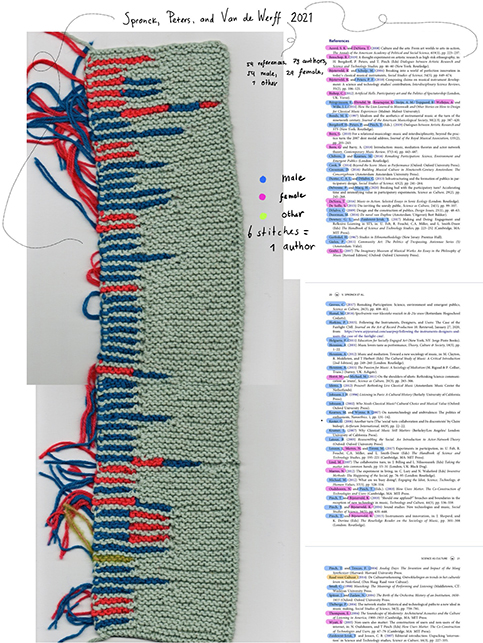

Yes! to your suggestion for us to collect some “other” (or: not traditionally academic) sources that inspire our work. While my writing cannot and does not happen without many sources of inspiration (like coffee, walks in nature, warm baths), if I follow this line of thinking the list becomes endless. Let me make a distinction: There are things that inspire me to work (that give me energy, a clear mind, rest) and things that inspire my work (that inspire my analysis, my writing style, my topical focus). As with everything, these two types of inspiration bleed into each other. But for the sake of not adding to the overwhelmedness I am already feeling, let me tell you about a few different sources of inspiration in the second sense. In trying to visualise the patchworky nature of how these different sources overlap, I have created a collage (Figure 3) that represents some of these sources.

First, one that you won’t find surprising. A novel. Or: novels as a category. I find inspiration in reading fiction—I know we both do. But there are some novels that stay with you and really influence your work. One of those novels for me is Claire Keegan’s Small Things Like These (2021). The observations and dialogues in this novel are so apt and portray the complexity of human nature so well. It has helped me think through the ways in which I want to theorise “messiness” in my work (see Law 2004; Forester 1984; Postill and Pink 2012). And also: The elegance and clarity of this book’s writing style are something I can only aspire to in my own writing—in my academic analyses as well as in my ethnographic vignettes.

A few other sources:

- A conversation I had with a student, which gave me a new and refreshing view on an academic text that I use in my work (May 3, 2024).

- Another conversation, even more fleeting: one that I overheard in the train. I observed some of my research findings “acted out” in real time between two friends (October 17, 2024).

- Doing some writing in a café and observing a bunch of kids and how drawn they are to phones and screens (December 12, 2024). This helped me think through the form of one of my dissertation’s chapters, on the materiality of online engagements.

- A panel discussion on academics in the media with Nadia Bouras I attended last month (November 27, 2024) and a related Volkskrant article (2024) that was published yesterday.

- The book Among Wolves (2017) by Timothy Pachirat. Such an interesting way of experimenting with form!

—Maud

– □ ×

From: Veerle <veerle.spronck@hku.nl>

To: Maud <m.oostindie@maastrichtuniversity.nl >

Sent: Friday, December 20, 2024, 11:13 AM

Dear Maud,

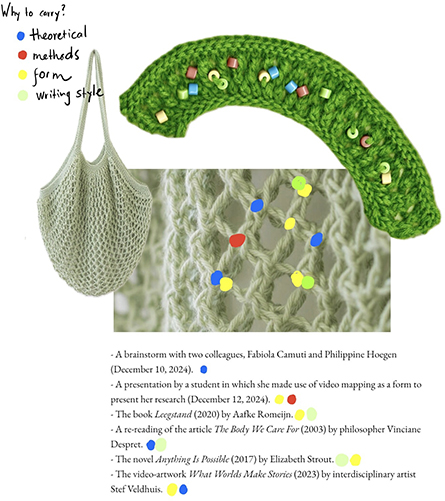

Interesting . . . I see some overlap between our sources (of course, novels!), but there are also some quite different things in my list:

- A brainstorm with two colleagues, Fabiola Camuti and Philippine Hoegen (this led to ideas for a new article, and a list of books and articles they recommended to me) (December 10, 2024).

- A presentation by a student in which she made use of video mapping as a form to present her research (it made me reconsider how I was preparing a conference presentation: My storytelling could become more interesting by using these technical means) (December 12, 2024).

- The book Leegstand (2020) by Aafke Romeijn (this helped me imagine how to combine more traditional academic essays with poems and visual material).

- A re-reading of the article “The Body We Care For” (2004) by philosopher Vinciane Despret (besides this being an important theoretical source in a project about embodied knowledge, it brought me lots of joy because it shows how vivid and funny academic writing can be).

- The novel Anything Is Possible (2017) by Elizabeth Strout (amazing way of building up a story, reminded me of detailed, aesthetic fieldnotes).

- The video artwork What Worlds Make Stories (2023) by interdisciplinary artist Stef Veldhuis (a very complex, nuanced argument about otherness and objectivity, completely told through visual means).

Clearly, many of these do not fit in my standard Mendeley system, and some actually do. Something to think about over the holidays!

—Veerle

– □ ×

From: Maud <m.oostindie@maastrichtuniversity.nl>

To: Veerle <veerle.spronck@hku.nl>

Sent: Tuesday, January 7, 2025, 09:03 AM

Dear Veerle,

Exactly! Several of these sources we collected do not fit our standard referencing systems. So if we want to do justice to them, where do we start? Your knitting and my collage/bricolage (see Lévi-Strauss 1962; Vaughan 2005) is a beginning. But maybe some metaphors can help us think through this further . . .

Carrie Mott and Daniel Cockayne say that citation counting is a way “to pay attention to whom we carry with us when we cite” (2017, 966). I love this way of putting it: whom we carry with us. We always talk about how we are carried by the people and ideas that came before us (the overused “standing on the shoulders of giants”). But we also actively carry people and ideas with us, on our way forward. Isn’t that beautiful? It emphasises our responsibility and agency as writers.

—Maud

PS Agreed on Anything Is Possible!

– □ ×

From: Veerle <veerle.spronck@hku.nl>

To: Maud <m.oostindie@maastrichtuniversity.nl >

Sent: Wednesday, January 8, 2025, 08:42 AM

Dear Maud,

Have you ever read Ursula Le Guin’s The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction ([1988] 2019)? I obviously had to think of it because of the “carrying” you mentioned. She reimagines stories—and explicitly novels!—as bags for collecting, carrying, and telling the “stuff” of living. In the essay, she argues that this act of carrying and collecting and sharing stories is fundamentally what makes us human. Following Le Guin, if our research attempts to make sense of the world, we should do justice to all of these bits and bobs.

Particularly relevant in relation to what you were writing is that she is not interested in linearity or hero stories. Rather, these bags are interesting to rummage through because they contain little things (objects, experiences, ideas) that we gathered along the way and those things tell stories about being human: “A leaf a gourd a shell a net a bag a sling a sack a bottle a pot a box a container. A holder. A recipient” (Le Guin [1988] 2019, 28–29). The metaphor helps me think . . . ! I am immediately visualising the references I collected last month in a new way: as a knitted carrier bag of references (Figure 4) full of different coloured bits. What is it in them that makes me want to carry them with me? And how might specifying that help me cite them?

—Veerle

– □ ×

From: Maud <m.oostindie@maastrichtuniversity.nl>

To: Veerle <veerle.spronck@hku.nl>

Sent: Monday, January 13, 2025, 09:04 AM

Dear Veerle,

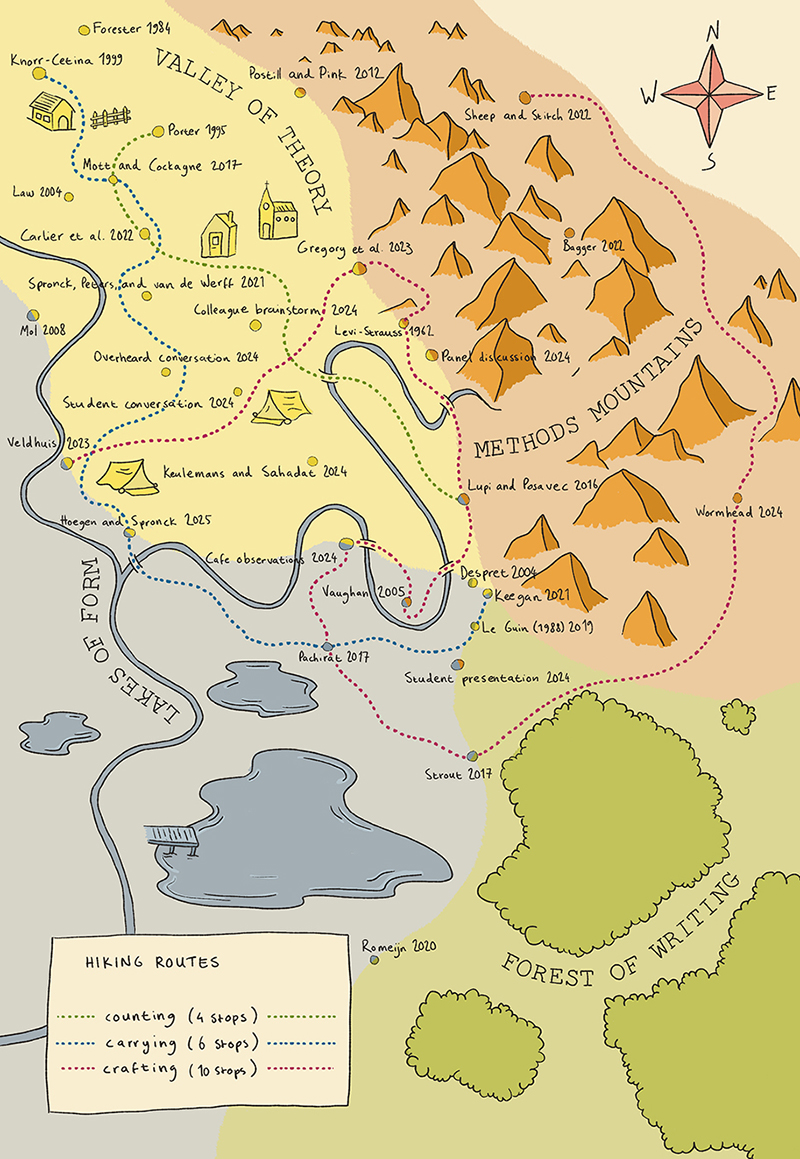

I like the image of the bag! But I want to introduce another image: that of the map. Because while I like the image of sources and inspiration jumbled together at the bottom of our carrier bag, I’m also interested in how they relate to each other. For this we might need other imagery that highlights the connections (like the nodes in your knitting pattern!). I’ve been playing around with a map idea. It could show where we got inspiration from, what exactly this source inspired, how it intersects with other lines of thinking . . . but it also shows the potential of the empty spaces on the map.

Could we use the “map as metaphor” to acknowledge these other sources in our academic writing? As an alternative reference system, if you will. Annemarie Mol argues that “it belongs to the art of academic writing to try to make (at least some of) the relations between a text and the literature explicit” (2008, 98). Yet, the rigid linearity of the standard reference list does not have space for the nodes, relationships, connections, and multiplicity of citational practices that we have highlighted in our exchange. So how about we create a kind of “reference map” (Figure 5)? With a map in hand, we can explore multiple routes through the landscape . . .

—Maud

– □ ×

From: Veerle <veerle.spronck@hku.nl>

To: Maud <m.oostindie@maastrichtuniversity.nl>

Sent: Monday, January 13, 2025, 15:33 PM

I like that idea, Maud, let’s try!

Reference Map

– □ ×

From: Maud <m.oostindie@maastrichtuniversity.nl>; Veerle <veerle.spronck@hku.nl>

To: Reader <reader@kulajournal.ca>

Sent: Friday, February 7, 2025, 05:19 PM

Dear Reader,

We think we might owe you some explanation after this unorthodox reference list. We actually created three separate reference “lists.” You’ve just seen the first one: the map. The map includes all of the sources we use in this article—in our written exchange and visual dialogue. Below, you’ll find two other lists (which are actual lists, don’t worry). These two are divided by how well they do or do not fit the standard Chicago style that KULA asks authors to use. First, a list with the “other” references that do not fit academic standards, and then the “regular” reference list that any article will have.

We tried to get to the bottom of feminist citational practices by not stopping after a counting process or an attempt to include more women. While acknowledging this as an important first step, we actively tried to make space for sources and inspiration that generally remain invisible, and we tried to put them in conversation/relation with the more classic academic sources. Oof, this was a complex and messy process! When we decided to try and create a map (instead of an alphabetical list), this forced us to be very aware of the language, narratives, and metaphors we use. For instance, we located theory in a valley for a specific reason: Valleys are highly populated areas and usually have lots of infrastructure. Theory, in an academic context, is the land we have explored well: We know its routes and structures. Some of the other areas are a lot less well travelled . . .

Moreover, the quality of a map—in opposition to a list—is that it allows you to see how certain sources are located: deep in the mountains, or on bordering land? Close together or far apart? Furthermore, a map allows the creation of “routes” to travel between sources that highlight a specific theme within our work. Creating the reference map did ask of us, as authors, to spend a lot (really, a lot) more time and thought on the organisation of our references. We worked hard to craft routes that would allow readers to see our work in multiple ways.

An important point to note, however, is that the reference map does not replace the more standard reference lists that follow below. Rather, it serves as an alternative that helps to render visible the specific and non-neutral form that our academic citational practices take. Not just for the sake of creating a pretty map, but to do more justice to what and whom we carry with us. It serves as an invitation to reflect, and to make an effort to move beyond routine ways of citing.

—Maud and Veerle

Acknowledgements

We thank Samantha MacFarlane and Sally Wyatt for their thoughtful comments and their enthusiasm for unusual forms of scholarship. We are also grateful to the participants of the Knitted Data Visualisations workshop organised by Loret Karman, whose feedback was a source of inspiration. Finally, we thank the wide range of influences—authors we cite, students who challenged us, colleagues who shared their thoughts, the joy we find in drawing and knitting, as well as artworks and novels that stayed with us—for shaping the textures of this work.

References

“OTHER” REFERENCES

Bouras, Nadia. 2024. Panel discussion, KNAW Faces of Science Day, Trippenhuis, Amsterdam, November 27.

Camuti, Fabiola, and Philippine Hoegen. 2024. Brainstorming session, HKU Nieuwekade, Utrecht, December 10.

Conversation with a student. 2024. Café Zondag, Maastricht, May 3.

Observations in a café. 2024. Centre Ceramique, Maastricht, December 12.

Overheard conversation on the train. 2024. NS train carriage, somewhere between Zwolle and Groningen, October 17.

Presentation by a student. 2024. HKU Jaarbeursplein, Utrecht, December 12.

Veldhuis, Stef. 2023. What Worlds Make Stories. Video artwork, Willem II, Den Bosch.

STANDARD REFERENCES

Bagger, Lærke. 2022. Close Knit. Prestel.

Carlier, Aurélie, Hang Nguyen, Lidwien Hollanders, Nicole Basaraba, Sally Wyatt, and Sharon Anyango. 2022. UM Citation Guide: A Guide by FEM. https://www.maastrichtuniversity.nl/file/umcitationguidefem2022pdf.

Choy, Davina. 2022. “Market Bag Knitting Pattern.” Sheep and Stitch. https://sheepandstitch.com/ pattern/market-bag-knitting-pattern-and-free-video-tutorial/.

Despret, Vinciane. 2004. “The Body We Care for: Figures of Anthropo-zoo-genesis.” Body & Society 10 (2–3): 111–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034x04042938.

Forester, John. 1984. “Bounded Rationality and the Politics of Muddling Through.” Public Administration Review 44 (1): 23–31. https://doi.org/10.2307/975658.

Gregory, Kathleen, Paul Groth, Andrea Scharnhorst, and Sally Wyatt. 2023. “The Mysterious User of Research Data: Knitting Together Science and Technology Studies with Information and Computer Science.” In Interdisciplinarity in the Scholarly Life Cycle: Learning by Example in Humanities and Social Science Research, edited by Karin Bijsterveld and Aagje Swinnen. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-11108-2_11.

Hoegen, Philippine, and Veerle Spronck. 2025. “How We Wish to Work: An Exchange on Participation, Connectivity, and Care.” Performance Research 29 (2):82–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/13528165.2024.2417566.

Keegan, Claire. 2021. Small Things Like These. Faber & Faber.

Keulemans, Maarten, and Ianthe Sahadat. 2024. “Nadia Bouras en Marcel Levi voeren pittig gesprek: ‘Antisemitisme bestrijd je niet met racisme.’” De Volkskrant, December 17. https://www.volkskrant.nl/wetenschap/nadia-bouras-en-marcel-levi-voeren-pittig-gesprek-antisemitisme-bestrijd-je-nietmet-racisme~b643ee61/.

Knorr Cetina, Karin. 1999. Epistemic Cultures: How the Sciences Make Knowledge. Harvard University Press.

Law, John. 2004. After Method: Mess in Social Science Research. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203481141.

Le Guin, Ursula K. (1988) 2019. The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction. Ignota.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 1962. The Savage Mind. University of Chicago Press.

Lupi, Giorgia, and Stefanie Posavec. 2016. Dear Data. Princeton Architectural Press.

Mol, Annemarie. 2008. The Logic of Care: Health and the Problem of Patient Choice. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203927076.

Mott, Carrie, and Daniel Cockayne. 2017. “Citation Matters: Mobilizing the Politics of Citation Toward a Practice of ‘Conscientious Engagement.’” Gender, Place & Culture 24 (7): 954–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369x.2017.1339022.

Pachirat, Timothy. 2017. Among Wolves: Ethnography and the Immersive Study of Power. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203701102.

Porter, Theodore M. 1995. Trust in Numbers: The Pursuit of Objectivity in Science and Public Life. Princeton University Press.

Postill, John, and Sarah Pink. 2012. “Social Media Ethnography: The Digital Researcher in a Messy Web.” Media International Australia 145 (1): 123–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878x1214500114.

Romeijn, Aafke. 2020. Leegstand. De Arbeiderspers.

Spronck, Veerle, Peter Peters, and Ties van de Werff. 2021. “Empty Minds: Innovating Audience Participation in Symphonic Practice.” Science as Culture 30 (2): 216–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/09505431.2021.1893681.

Strout, Elizabeth. 2017. Anything Is Possible. Random House.

Vaughan, Kathleen. 2005. “Pieced Together: Collage as an Artist’s Method for Interdisciplinary Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 4 (1): 27–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690500400103.

Wormhead, Woolly. 2024. Short-Row Colorwork Knitting. Sixth & Spring Books.