COMMENTARY

Demanding Epistemic Justice: Indigenous Youth as Indigenous Science Diplomats for a Sustainable Future

Heather Sauyaq Jean Gordon

University of Alaska Fairbanks, American University, and University of Johannesburg

This commentary begins with the author's background, which leads into explaining Indigenous Ways of Knowing, Knowledges, and Sciences. It examines the significance of Indigenous kinship perspectives offering a sustainable way to live, inherent in many Indigenous cultures. It then explores colonial epistemicide, evolving knowledge pluralism, and how to co-produce knowledge needed for evidence-based decision-making. It concludes with a discussion of the transformative role of Indigenous youth in demanding epistemic justice by serving as Indigenous Science Diplomats, promoting knowledge pluralism in evidence-based policy. These young leaders bridge ways of knowing and span power structures and cultural, epistemological, and disciplinary divides, fostering a more inclusive sustainability in the face of climate change. The commentary underscores the importance of empowering Indigenous youth as key actors in creating a sustainable future and advocates for greater recognition and integration of Indigenous Knowledges and Sciences in policy and practice, promoting a path toward epistemic justice and a sustainable planet.

Keywords: Indigenous youth; boundary spanners; science diplomats; knowledge pluralism; epistemic justice; science communication

How to cite this article: Gordon, Heather Sauyaq Jean. 2025. Demanding Epistemic Justice: Indigenous Youth as Indigenous Science Diplomats for a Sustainable Future. KULA: Knowledge Creation, Dissemination, and Preservation Studies 8(1). https://doi.org/10.18357/kula.301

Submitted: 28 January 2025 Accepted: 05 March 2025 Published: 27 May 2025

Competing interests and funding: The author has no competing interests.

Copyright: © 2025 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Background

I am Iñupiaq and a Tribal citizen of the Nome Eskimo Community in Alaska. My Iñupiaq family has lived with colonization since first contact, including the 1900s flu epidemic and the cultural and language erasure imposed by assimilationist boarding schools. My family worked to maintain our culture and land-based life, and I grew up on my grandmother’s homestead and reindeer ranch outside of Homer, Alaska, on Dena’ina Ełnena (Dena’ina homelands) in the Ninilchik Village Tribe’s region. I sought higher education to advocate for Indigenous ways of knowing and life, which culminated in a PhD in Indigenous Studies, with a focus on Indigenous Sustainability Science. I wanted to know the world from the Iñupiaq way I was raised and to understand Euroamerican perspectives that my mother was from. I share this narrative to help the reader understand who I am (positionality) and my perspective (reflexivity) with an identity—rooted in place, family, and community—before my credentials, reflecting the Iñupiaq values (Iñupiat Ilitqusiat) I was raised with: sharing, knowledge of family tree, knowledge of language, humility, respect for Elders, respect for others, cooperation, hard work, love for children, avoiding conflict through openness, family roles, spirituality, humor, respect for nature, domestic skills, hunter success, and responsibility to Tribe (Topkok 2015). Through this lens, I acknowledge my relations, ancestors, mentors, and the knowledge keepers who have guided my journey.

My life has been a journey of learning. I learn Indigenous Knowledges through oral history stories and watching my family, observing, apprenticing, and doing (Kawagley 2006). I learn dominant society paradigms in schools through books and lectures. I have learned about different knowledge systems that have given me many lenses through which to view and attempt to understand the world and all those within it—human beings, non-human beings (i.e., plants, animals, clouds), non-human collectives (i.e., watersheds, prairies), and “more-than-human” beings (i.e., spirits) (Larsen and Johnson 2016; Whyte et al. 2016). I was immersed in the dominant knowledge system (often called Western or Euroamerican) through schooling. These institutions are based on controlling knowledge access through colonial and systemically racist systems that have sought to devalue, silence, and destroy Indigenous Ways of Knowing through assimilation practices like past boarding schools and the ongoing exclusion of Indigenous Sciences, histories, languages, and cultures in formal schooling curricula (St. Denis 2007). Indigenous Ways of Knowing and knowledges are unmentioned, and our technology and innovation either unrecognized or appropriated, considered to come from dominant cultures (Roht-Arriaza 1995). This is epistemicide, an injustice that seeks to invalidate, destroy, and erase a system of knowledge. Absence does not mean these do not exist, and it is critical societally that we first unlearn that there is only one way of knowing, and take the time to relearn through pluralism.

Indigenous Ways of Knowing

Indigenous Ways of Knowing (drawing from many similarities, not one monolithic way of knowing) approach the world through different cosmologies (belief of our origins), epistemologies (what we know), ontologies (what exists), and axiologies (values and ethics) than dominant society. We see all beings, human and non-human (i.e., animal, plant, water, air, fire, Mother Earth) as interconnected, with survival of one dependent on all the others (Salmón 2000). Within Indigenous cosmologies and ontologies, humans are one being in a world of many beings, part of broader ecological systems. All human and non-human beings sustain one another, caring for each other and Mother Earth, who houses all life (Muir et al. 2010). Indigenous epistemologies recognize that humans depend on Mother Earth, who relies on humans to nurture her so that she can continue sustaining life. Not only are all beings interconnected, but our axiologies see them as connected by kinship relationships, exchange, support, nurturance, and dependence on one another. Indigenous epistemologies and axiologies ultimately influence our praxeologies (how we act and practice); we approach non-human beings such as Water with respect, requesting access to take some, but not too much. Our cosmologies, epistemologies, ontologies, and axiologies are not anthropocentric; they do not center humans but draw on a broader perspective of life as an extended family kinship network which shapes how we act.

In Euroamerican society, decisions are often rooted in human exceptionalism, positioning humans as separate from and above all other beings (discussed by Kim et al. 2023). This view treats the non-human world as “resources” for human use, not kin. In contrast, Indigenous perspectives value humility and relationality (Topkok 2015). The Euroamerican system prioritizes humans before all other lives, selfish and unsustainable, neglecting the need to care for Mother Earth for future generations as our ancestors did for us (Kim et al. 2023). The contrast is between hierarchical systems (extractive societies) and kinship-based systems (typically Indigenous and circular) (Whyte 2021), where kinship recognizes all beings as relatives and honors the responsibility to care for them as we would our human families. Indigenous Ways of Knowing see the land, waters, and Mother Earth as sacred while a human exceptionalist approach prioritizes extraction and capitalistic profit, often at the expense of the natural world, polluting the lands, waters, and air for money.

This way of knowing guides Indigenous praxeologies and ultimately our sciences, specifically the cosmologies, epistemologies, ontologies, and axiologies that all center relationality and kinship (Keali‘ikanaka‘oleohaililani 2016; Salmón 2000). Dominant science paradigms revolve around the written word, ignoring oral history and the ability to share knowledge through story and example and to learn through apprenticeship and doing (Kawagley 2006). Indigenous Peoples employ protocols that guide us in how to approach, proceed, and behave, recognizing that science is inherently not objective in any culture, form, or way of knowing (Whyte et al. 2016). Relationships, decision-making, and choice in science make it subjective and tied to reciprocal relationships with the world. As Whyte et al. (2016) explain, “There are no strong reasons we can identify as to why approaching the world with humility, respect for the diversity of knowledges of humans and non-humans, and a responsibility to honor other beings, entities and collective as animate, is any less conducive to engaging in dialog with a range of forms of empirical inquiry, including those forms of empirical inquiry in sustainability science.” Indigenous Ways of Knowing include Indigenous Sciences, of which the oft discussed Traditional Ecological Knowledges are only a small part.

Colonization and Epistemicide

When colonizers arrived in the United States, they viewed the land as a beautiful garden (Curry 2021), assuming it existed naturally and was uninhabited under the principle of terra nullius, which deemed lands empty if not occupied by Christians (Zukas 2005). Over time, as they forcibly removed and killed Indigenous Peoples, the landscape changed dramatically, no longer resembling the garden they once admired but instead becoming unmanaged and overgrown in areas and overused and polluted in others (Yonk et al. 2018). Despite this, the US government continued to corral Indigenous Peoples onto reservations, attempt to assimilate us through erasing our Ways of Knowing, cultures, and languages, and exploit the natural world for wealth. Indigenous Knowledges had sustainably managed and protected these lands and waters for millennia. Yet, in just 250 years, the planet now faces climate change, record temperatures, devastating fires, undrinkable water, and other crises, leaving children fearful for their future and hopeless about reaching old age (Hickman et al. 2021).

This is deeply concerning for two reasons. One, epistemicide, the erasure of Indigenous Ways of Knowing within the US and replacing it with Euroamerican ways of knowing as the only way of knowing (Hatch et al. 2023). And two, when thinking of evidence used for policy and decision-making, if Indigenous Knowledges and Sciences are called anecdotal and ignored then Indigenous people are not considered experts or epistemic authorities. Indigenous Sciences are still rarely, if ever, used in evidence-based policy, and epistemic authority rests predominantly with written Euromerican systems, certifications like PhDs, and colonial governments.

When considering knowledge, how can one society or culture extinguish another knowledge system, stating theirs is superior to any other and denying that any other way is not knowledge at all (Redvers et al. 2024)? This is a practice of colonization, where brute force is used instead of earned, or what can be considered legitimate, epistemic authority (Clifton et al. 2018). Many colonizing groups have established boarding schools aimed at erasing Indigenous Ways of Knowing, cultures, and languages (Marker 2009). This tactic reflects a broader trend of epistemic injustice, where dominant knowledge systems extinguish another way of knowing. First, colonizers call the colonized savage and unintellectual, claiming colonial knowledge will civilize them (Memmi 1965). Then they work to discredit the idea that the savage people had any way of knowing beyond anecdotes and thus have no knowledge holders, knowledge, evidence, scientists, experts, or epistemic authorities (Fricker 2007). This strategy not only seeks to delegitimize Indigenous Knowledges and Sciences but erase them, excluding them entirely from decision-making for the most informed future (Wheeler and Root‐Bernstein 2020). This epistemic oppression that Indigenous Peoples face through epistemic exclusion, which infringes on their epistemic agency to engage in knowledge production and inform decision-making, is steeped in ongoing colonization and systemic racism, requiring epistemic decolonization (Berenstain et al. 2022; Dotson 2014; Mitova 2024; Tobi 2022).

Pluralism, Two-Eyed Seeing, Multiple Ways of Knowing for Informed Decision-Making

Indigenous and Euroamerican cosmologies, epistemologies, ontologies, and axiologies are not the same. One does not encompass the other, and they do not necessarily overlap. They are incommensurate, with no standard to measure them against one another. It is an apples and oranges situation, with the one commonality being that they are fruit but there being no way to judge one according to the standards of the other. Each of them has different conceptions of what they consider science, evidence, expertise, and epistemic authority, as explained above. This does not mean one way of knowing is right and another is wrong, or one is better than the other; these are both able to exist separately from one another. Indigenous Peoples recognize the importance of braiding knowledge systems together through our youth learning their cultures’ oral histories as well as attending schools and universities. We do not see a weakening of one knowledge system when complemented with another because we are not focused on the hierarchy of epistemic authority; instead, our priority is identifying the most accurate and relevant information to guide decision-making. This is especially crucial as we confront climate-related disasters such as typhoons, hurricanes, permafrost melt, fires, and erosion, which exacerbate the ongoing challenges of colonialism as an ongoing disaster faced by our communities.

However, many decision-makers are used to quantified information in graphs and tables. Indigenous storytelling as evidence challenges people not used to engaging in multiple ways of knowing, whether referred to as epistemological pluralism (Ahenakew 2014), heterogeneous knowledge systems (Tsuji and Ho 2002), or two-eyed seeing (Peltier 2018). Heterogeneous knowledge systems specifically call out that there are not only two ways of knowing and that knowledge systems are more than only epistemology. Heterogeneous knowledge systems recognize pluralism in ways of knowing with distinct knowledge systems existing separately from one another, with different epistemologies, ontologies, and axiologies, that are each able to provide epistemic value and have experts. These lead to different praxeologies that produce distinct forms of evidence, which, when used together, result in a broader evidence base and support better decision-making. This pluralistic approach is not seeking to prove anyone wrong but to bring everyone to the table to discuss and share. Indigenous Knowledge holders seek epistemic justice, to have their knowledges and histories recognized as legitimate, taught in schools instead of being marginalized, and for knowers to be respected in their capacity as epistemic agents (Tsosie 2012). This outcome requires decolonizing knowledge by removing hierarchy, dismantling oppressive power structures upheld through epistemic supremacy, and bringing to the center marginalized knowledge systems to engage with currently dominant systems (Manathunga et al. 2021). Epistemic justice is necessary for the empowerment of Indigenous Peoples to be self-determining, essential for well-being (Dudgeon and Bray 2023). It not only supports anti-racism and decolonization in decision-making but creates a society based on epistemic pluralism, one that recognizes multiplicity and diversity in knowledges and draws on all ways of knowing for the most informed decision-making (Guibrunet et al. 2024).

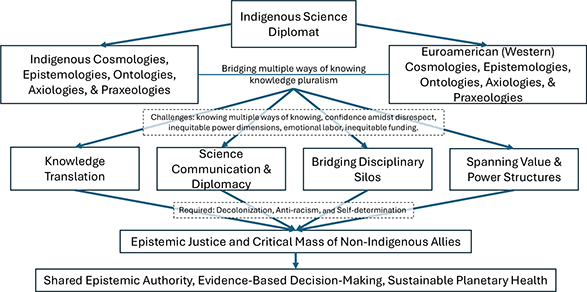

Indigenous Youth Science Diplomats: Building Bridges Through Knowledge Translation and Science Communication

Having been raised in multiple knowledge systems with different cosmologies, epistemologies, ontologies, and axiologies, I have spent my life learning to communicate concepts across multiple ways of knowing, in different disciplines, at different power levels, and across value systems. These experiences in boundary spanning, knowledge translation, and science diplomacy have coalesced into what I call Indigenous Science Diplomacy, something unique requiring a combination of the above skills. This includes understanding multiple knowledge systems, translating between different ways of knowing, bridging gaps across silos (whether disciplinary, institutional), and spanning power structures and systems (such as between minoritized and marginalized communities and scientists and policy makers) (Hatch et al. 2023; Hoffman et al. 2024; Safford et al. 2017). Indigenous Science Diplomacy also requires translating knowledge, science, and evidence into different epistemologies, ontologies, and axiologies, not only code-switching but decontextualizing and then recontextualizing knowledge (Burke 2009; Kennedy et al. 2024). This practice moves information in both directions and is relevant to multiple ways of knowing and those in different power structures and systems (i.e., the community and policy-makers). However, without science communication skills, translating complex scientific concepts across ways of knowing to non-experts would also not be possible (Hatch et al. 2023). Finally, science diplomacy is a critical skill, bringing science into policy space and using “science cooperation to help build bridges and enhance relationships between and amongst societies” (Turekian as cited in CORDIS 2009). But what makes an Indigenous Science Diplomat unique? They can boundary span, translate knowledge, communicate science, and be science diplomats for scientific concepts in multiple ways of knowing. Additionally, Indigenous Science Diplomats seem to be expected to be educators, without other parties putting in the work themselves to learn about other ways of knowing.

Being an Indigenous Science Diplomat comes with heavy burdens and multiple expected roles, which makes it challenging and often leads to burnout. Rudolf et al. (forthcoming) explain that Indigenous individuals in boundary-spanning roles are pulled in many directions as they serve their community and multiple organizations in addition to caring for themselves. These people are “in between,” making change, liaising, building relationships, engagement experts and so much more (Rudolf et al., forthcoming). When the challenges of boundary spanning are combined with science diplomacy, science communication, and knowledge translation, they are further compounded. As Hatch et al. (2023), Peltier (2018), Rudolf et al. (forthcoming), and Itchuaqiyaq (2022) explain, some challenges put on these individuals include:

- Having an intricate understanding of multiple ways of knowing and an ability to see the world through multiple lenses at the same time

- Advocating for Indigenous Knowledges and Sciences, combating stereotypes, colonization, and racism in the process

- Knowing how to translate knowledges, interpret, and contextualize values and actions to contextualize data and evidence

- Having the confidence to speak up for and be responsible to both communities and other parties, which involves standing up for their own community, addressing power dynamics, and holding other parties accountable

- Being perceived as actual diplomats, and understood as speaking on behalf of all their Nation or even all Indigenous Peoples against their wishes

- Suffering emotional labor and burnout

- Dealing with inequitable funding and exclusion

Indigenous Youth as Indigenous Science Diplomats

Indigenous communities and Tribes have identified their youth as key actors in creating a sustainable future, advocating for greater recognition and integration of Indigenous Knowledges and Sciences in policy and practice, advocating on behalf of their Tribes, and promoting a path toward epistemic justice and a sustainable and healthy planet (Redvers et al. 2024; Sogbanmu et al. 2023). These youth have grown up learning multiple ways of knowing, and it is critical to prioritize their voices as they face an uncertain future many of us will be absent from. Indigenous youth are taking up this responsibility and honor, inserting themselves into spaces where Indigenous people have been excluded for years. They are fighting to be at the table; even if not invited, they show up and pull up their own chair (Arctic Youth Ambassadors 2023). Indigenous youth are not asking for epistemic justice as much as they are striving for it, requiring and demanding it.

In Arctic spaces they engage with non-Indigenous youth through organizations like Arctic Youth Ambassadors, Arctic Youth for Environmental Action, and Students on Ice as well as through social media videos and posts. These youth expand the praxis of Indigenous Science Diplomacy by building allies in the non-Indigenous community, teaching them about other ways of knowing and about how to see the world through pluralism (see Figure 1 for the path of the Indigenous Science Diplomat). As youth today face an uncertain future due to climate change—an existential threat—they are beginning to share a perspective of the world that centers relationality and recognizes the damage of anthropocentrism and human exceptionalism, to ultimately create a unity across ways of knowing (Gienger et al. 2024; Nelson 2020). Indigenous and non-Indigenous youth are speaking together, co-developing messages and expressions grounded in multiple ways of knowing (Stirling et al 2023; Lee and Chen 2014; Pellett 2023).

Figure 1. The pathway of the Indigenous Science Diplomat. Created by Heather Sauyaq Jean Gordon.

Organizations like those in the Arctic as well as the Global Indigenous Youth Summit on Climate Change—a global conference held for twenty-four hours across three eight-hour time zones by, for, and among Indigenous youth, broadly inclusive of all attendees—create spaces for relationship and trust-building between Indigenous and non-Indigenous youth (Sogbanmu et al. 2023). In these spaces youth learn about each other, share with one another, and create trust across ways of knowing, languages, national borders, and racial/ethnic boundaries. Together these young people can support one another and build a critical mass to create change, emphasizing that systems change is key, that it is the role of everyone to understand multiple ways of knowing.

These youth are our future, our science diplomats, science communicators, boundary spanners, epistemic agents, and leaders. They propose solutions and actively engage in learning, encouraging others to unlearn stereotypes, biases, colonialism, xenophobia, racism, ethnocentrism, and notions of epistemic authority. In doing so, they advocate for learning what we need to unlearn in order to relearn, a process that embraces the pluralism of ways of knowing, enabling more informed decisions that promote the survival of all beings in a sustainable manner. We must empower Indigenous youth to be leaders, building relationships with non-Indigenous youth for a sustainable future, advocating for greater recognition and integration of Indigenous Knowledges and Sciences in policy and practice, promoting allyship and a path toward epistemic justice and a sustainable planet. I am hopeful for the future; the futurist in me knows there are countless futures and possibly even more ways to move towards epistemic justice than away from it.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the African Centre for Epistemology and Philosophy of Science at the University of Johannesburg, South Africa, for the opportunity to attend the Connecting Indigenous Knowledge in the Global North and Global South conference, as this opportunity led to the author gaining a critical understanding of epistemicide and the importance of Indigenous communities in the Global North and Global South engaging in scholarship and writing that connects each other’s work.

References

Ahenakew, Cash. 2014. “Indigenous Epistemological Pluralism: Connecting Different Traditions of Knowledge Production.” Canadian Journal of Native Education 37 (1). https://doi.org/10.14288/cjne.v37i1.196560.

Arctic Youth Ambassadors. 2023. “Why Youth Engagement and Leadership?” Presented at the Arctic Circle Assembly, Reykjavik, Iceland, October 16–18.

Berenstain, Nora, Kristie Dotson, Julieta Paredes, Elena Ruíz, and Noenoe K. Silva. 2022. “Epistemic Oppression, Resistance, and Resurgence.” Contemporary Political Theory 21 (2): 283–314. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41296-021-00483-z.

Burke, Peter. 2009. “Translating Knowledge, Translating Cultures.” In Kultureller Austausch: Bilanz und Perspektiven der Frühneuzeitforschung, edited by Michael North. Böhlau.

Clifton, Jonathan, Dorien Van De Mieroop, Prachee Sehgal, and Aneet. 2018. “The Multimodal Enactment of Deontic and Epistemic Authority in Indian Meetings.” Pragmatics 28 (3): 333–60. https://doi.org/10.1075/prag.17011.cli.

CORDIS – EU Research Results. 2009. “Science as a Tool for International Diplomacy.” Publications Office of the European Union. https://cordis.europa.eu/article/id/30532-science-as-a-tool-for-international-diplomacy.

Curry, Andrew. 2021. “Pacific Northwest’s ‘Forest Gardens’ Were Deliberately Planted by Indigenous People.” Science, April 22. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abj1396.

Dotson, Kristie. 2014. “Conceptualizing Epistemic Oppression.” Social Epistemology 28 (2): 115–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2013.782585.

Dudgeon, Pat, and Abigail Bray. 2023. “The Indigenous Turn: Epistemic Justice, Indigenous Knowledge Systems, and Social and Emotional Well-Being.” In Handbook of Critical Whiteness: Deconstructing Dominant Discourses Across Disciplines, edited by Jioji Ravulo, Katarzyna Olcoń, Tinashe Dune, Alex Workman, and Pranee Liamputtong. Springer Nature Singapore.

Fricker, Miranda. 2007. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford University Press.

Gienger, Ariane, Melissa Nursey-Bray, Dianne Rodger, Anna Szorenyi, Philip Weinstein, Scott Hanson-Easey, Damien Fordham, Danielle Lemieux, Celeste Hill, and Shoko Yoneyama. 2024. “Responsible Environmental Education in the Anthropocene: Understanding and Responding to Young People’s Experiences of Nature Disconnection, Eco-Anxiety, and Ontological Insecurity.” Environmental Education Research 30 (9): 1619–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2024.2367022.

Guibrunet, Louise, David González-Jiménez, Gabriela Arroyo-Robles, Mariana Cantú-Fernández, Victoria Contreras, Daniela Flores Mendez, Arlen Valeria Ocampo Castrejón, Bosco Lliso, Ana Sofía Monroy-Sais, Tuyeni H. Mwampamba, Unai Pascual, Brigitte Baptiste, Mike Christie, and Patricia Balvanera. 2024. “Geographic and Epistemic Pluralism in the Sources of Evidence Informing International Environmental Science-Policy Platforms: Lessons Learnt from the IPBES Values Assessment.” Global Sustainability 7: e36. https://doi.org/10.1017/sus.2024.23.

Hatch, Marco B. A., Julia K. Parrish, Selina S. Heppell, Skye Augustine, Larry Campbell, Lauren M. Divine, Jamie Donatuto, Amy S. Groesbeck, and Nicole F. Smith. 2023. “Boundary Spanners: A Critical Role for Enduring Collaborations Between Indigenous Communities and Mainstream Scientists.” Ecology & Society 28 (1): 41. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-13887-280141.

Hickman, Caroline, Elizabeth Marks, Panu Pihkala, Susan Clayton, R. Eric Lewandowski, Elouise E. Mayall, Britt Wray, Catriona Mellor, and Lise van Susteren. 2021. “Climate Anxiety in Children and Young People and Their Beliefs About Government Responses to Climate Change: A Global Survey.” The Lancet Planetary Health 5 (12): e863–e873. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00278-3.

Hoffman, Kira M., Kelsey Copes-Gerbitz, Sarah Dickson-Hoyle, Mathieu Bourbonnais, Jodi Axelson, Amy Cardinal Christianson, Lori D. Daniels, Robert W. Gray, Peter Holub, Nicholas Mauro, Dinyar Minocher, and Dave Pascal. 2024. “Boundary Spanners Catalyze Cultural and Prescribed Fire in Western Canada.” FACETS 9: 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2023-0109.

Itchuaqiyaq, Cana Uluak. 2022. “No, I Won’t Introduce You to My Mama: Boundary Spanners, Access, and Accountability to Indigenous Communities.” Community Literacy Journal 17 (1). https://doi.org/10.25148/CLJ.17.1.010653.

Kawagley, Oscar Angayuqaq. 2006. A Yupiaq Worldview: A Pathway to Ecology and Spirit. 2nd ed. Waveland Press.

Keali‘ikanaka‘oleohaililani, Kekuhi, and Christian P. Giardina. 2016. “Embracing the Sacred: An Indigenous Framework for Tomorrow’s Sustainability Science.” Sustainability Science 11: 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-015-0343-3.

Kennedy, Michelle, Melody Morton Ninomiya, Maya Morton Ninomiya, Simon Brascoupé, Janet Smylie, Tom Calma, Janine Mohamed, Paul J. Stewart, and Raglan Maddox. 2024. “Knowledge Translation in Indigenous Health Research: Voices from the Field.” The Medical Journal of Australia 221 (1): 61–67. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.52357.

Kim, Joan J. H., Nicole Betz, Brian Helmuth, and John D. Coley. 2023. “Conceptualizing Human–Nature Relationships: Implications of Human Exceptionalist Thinking for Sustainability and Conservation.” Topics in Cognitive Science 15 (3): 357–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.12653.

Larsen, Soren C., and Jay T. Johnson. 2016. “The Agency of Place: Toward a More-Than-Human Geographical Self.” GeoHumanities 2 (1): 149–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/2373566X.2016.1157003.

Lee, Leemen, and Peiying Chen. 2014. “Empowering Indigenous Youth: Perspectives from a National Service Learning Program in Taiwan.” International Indigenous Policy Journal 5 (3): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2014.5.3.4.

Manathunga, Catherine, Jing Qi, Tracey Bunda, and Michael Singh. 2021. “Working Towards Future Epistemic Justice: Incorporating Transcultural and Indigenous Knowledge Systems in Doctoral Education.” In The Future of Doctoral Research, edited by Anne Lee and Rob Bongaardt. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003015383-8.

Marker, Michael. 2009. “Indigenous Resistance and Racist Schooling on the Borders of Empires: Coast Salish Cultural Survival.” Paedagogica Historica 45 (6): 757–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/00309230903335678.

Memmi, Albert. 1965. The Colonizer and the Colonized. Orion Press.

Mitova, Veli. 2024. “Can Theorising Epistemic Injustice Help Us Decolonise?” Inquiry (March): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020174X.2024.2327489.

Muir, Cameron, Deborah Rose, and Phillip Sullivan. 2010. “From the Other Side of the Knowledge Frontier: Indigenous Knowledge, Social–Ecological Relationships and New Perspectives.” The Rangeland Journal 32 (3): 259–65. https://doi.org/10.1071/RJ10014.

Nelson, Kristin. 2020. “Making Meaning in the Anthropocene: A Constructivist Grounded Theory Investigation of College Student Response to Planetary Ecological Crises.” PhD diss., University of Massachusetts Amherst. https://doi.org/10.7275/k5ft-tv60.

Pellett, Carinna. 2023. “Reconciliation of Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Youth Through Leadership Programs.” PhD diss., Laurentian University. https://laurentian.scholaris.ca/handle/10219/4066.

Peltier, Cindy. 2018. “An Application of Two-Eyed Seeing: Indigenous Research Methods with Participatory Action Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 17 (1). https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918812346.

Redvers, Nicole, Amali U. Lokugamage, João Paulo Lima Barreto, Madhu Bajra Bajracharya, and Matthew Harris. 2024. “Epistemicide, Health Systems, and Planetary Health: Re-Centering Indigenous Knowledge Systems.” PLOS Global Public Health 4 (8): p.e0003634. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003634.

Roht-Arriaza, Naomi. 1995. “Of Seeds and Shamans: The Appropriation of the Scientific and Technical Knowledge of Indigenous and Local Communities.” Michigan Journal of International Law 17 (4): 919–65. https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjil/vol17/iss4/2.

Rudolf, Margaret, Kaare Erickson, Lauren Divine, Henry Huntington, Eva Dawn Burk, Adelhied Herrmann, Krista Heeringa, Janessa Esquible, Karli Tyance Hassell, Mellisa Johnson, Craig Chythlook, Harmony Wayner, and Elizabeth Figus. Forthcoming. “What We See in the In-Between’: Navigating Ethics and Equity in the Role of Leading Research Projects with Alaska Native Communities.” Arctic Science.

Safford, Hugh D., Sarah C. Sawyer, Susan D. Kocher, J. Kevin Hiers, and Molly Cross. 2017. “Linking Knowledge to Action: The Role of Boundary Spanners in Translating Ecology.” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 15 (10): 560–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1731.

Salmón, Enrique. 2000. “Kincentric Ecology: Indigenous Perceptions of the Human-Nature Relationship.” Ecological Applications 10 (5): 1327–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/2641288.

Sogbanmu, Temitope Olawunmi, Heather Sauyaq Jean Gordon, Lahcen El Youssfi, Fridah Dermmillah Obare, Seira Duncan, Marion Hicks, Khadeejah Ibraheem Bello, Faris Ridzuan, and Adeyemi Oladapo Aremu. 2023. “Indigenous Youth Must Be at the Forefront of Climate Diplomacy.” Nature 620 (7973): 273–76. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-02480-1.

St. Denis, Verna. 2007. “Aboriginal Education and Anti-Racist Education: Building Alliances Across Cultural and Racial Identity.” Canadian Journal of Education 30 (4): 1068–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/20466679.

Stirling, Kasey M., Kaitlin Almack, Nicholas Boucher, Alexander Duncan, Andrew M. Muir, Jared W. H. Connoy, Valoree S. Gagnon, Ryan J. Lauzon, Kate J. Mussett, Charity Nonkes, Natalija Vojno, and Andrea J. Reid. 2023. “Experiences and Insights on Bridging Knowledge Systems Between Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Partners: Learnings from the Laurentian Great Lakes.” Journal of Great Lakes Research 49 (Supplement 1): S58–S71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jglr.2023.01.007.

Topkok, Charles Sean Asikłuk. 2015. “Iñupiat Ilitqusiat: Inner Views of Our Iñupiaq Values.” PhD diss., University of Alaska Fairbanks. http://hdl.handle.net/11122/6405.

Tobi, Abraham. 2022. “Epistemic Injustice and Colonisation.” South African Journal of Philosophy 41 (4): 337–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/02580136.2023.2199605.

Tsosie, Rebecca. 2012. “Indigenous Peoples and Epistemic Injustice: Science, Ethics, and Human Rights.” Washington Law Review 87 (4): 1133.

Tsuji, Leonard J. S., and Elise Ho. 2002. “Traditional Environmental Knowledge and Western Science: In Search of Common Ground.” Canadian Journal of Native Studies 22 (2): 327–60.

Wheeler, Helen C., and Meredith Root‐Bernstein. 2020. “Informing Decision‐Making with Indigenous and Local Knowledge and Science.” Journal of Applied Ecology 57 (9): 1634–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13734.

Whyte, Kyle Powys. 2021. “Time as Kinship.” In The Cambridge Companion to Environmental Humanities, edited by Jeffrey Cohen and Stephanie Foote. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009039369.005.

Whyte, Kyle Powys, Joseph P. Brewer II, and Jay T. Johnson. 2016. “Weaving Indigenous Science, Protocols and Sustainability Science.” Sustainability Science 11: 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-015-0296-6.

Yonk, Ryan M., Jeffrey C. Mosley, and Peter O. Husby. 2018. “Human Influences on the Northern Yellowstone Range.” Rangelands 40 (6): 177–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rala.2018.10.004.

Zukas, Alex. 2005. “Terra Incognita/Terra Nullius: Modern Imperialism, Maps, and Deception.” In Lived Topographies and Their Mediational Forces, edited by Gary Backhaus and John Murungi. Lexington Books.