EXHIBITION ARTICLE

Revisiting Ranganathan: The Making of Rule N°5

A.M. Alpin

New York University

Amanda Belantara

New York University

Rule N°5: The Library Is a Growing Organism is a collaboratively created installation located in NYU's main library that centers the voices of library workers in six sculptures. The work takes its name from Ranganathan's five laws or "rules" of library science published in 1931 and focuses on how the spirit of the fifth rule or law, which reads "the library is a growing organism," continues to inform the life and work of the library. As an interactive audio experience, Rule N°5 invites listeners to open doors and drawers, plug in, and push buttons to explore what it means to collect the world's knowledge, preserve the past, and shape the future. Rule N°5 examines practices and objects that shape how we can search, who we will find, and what we remember.

In this article, the makers behind the installation share stories of the project's creation and a deeper inspection of the invisible labor and conversations about questions of power, authority, and the politics of seemingly innocuous library work that inform the work.

Keywords: libraries; audiovisual installations; curation; knowledge organization; sound art; librarians

How to cite this article: How to cite this article: Alpin, A.M., and Amanda Belantara. 2025. Revisiting Ranganathan: The Making of Rule N° 5. KULA: Knowledge Creation, Dissemination, and Preservation Studies 8(2). https://doi.org/10.18357/kula.288

Submitted: 16 February 2024 Accepted: 23 August 2024 Published: 15 July 2025

Competing interests and funding: The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Copyright: © 2025 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Books are for use.

Every person his or her book.

Every book its reader.

Save the time of the reader.

A library is a growing organism.- S. R. Ranganathan, The Five Laws of Library Science (1931)

Introduction: Rule N° 5 & the Hidden Worlds of Library Work

“A library is a growing organism,” reads the fifth law or “rule” of library science as penned in 1931 by library science pioneer S. R. Ranganathan. One of the earliest philosophical foundations of librarianship, Ranganathan’s five laws remain central to the profession and are widely taught to the next generation of librarians (Rubin 2015). While they have been modified and even rewritten,1 Ranganathan’s original version remains a trusted guidepost through societal and technological changes. In a world where “library” and “book” have taken on vast new meanings, it is the last of Ranganathan’s five principles that prompts us to respond to the current environment and deeply interrogate the ways we curate, collect, organize, and preserve information. Libraries are treasured and contentious spaces within the public imagination and while much has changed since 1931, one aspect of the library has remained constant: it is created and maintained by library workers. While many scholarly and popular books investigate the histories and cultural meanings of libraries, Rule N° 5: The Library Is a Growing Organism centers the workers at the heart of these institutions. In this interactive installation, their voices reveal to listeners the mysterious, complicated, and controversial world of libraries. As Ranganathan’s fifth rule reminds us, libraries are socially constructed, living, breathing creatures that grow and change over time in accordance with the care and interests of those who create, use, and maintain them. Who decides what is collected? What does it mean to attempt to select, preserve, and organize materials in the midst of social and environmental crises? What exactly are libraries trying to save and for whom? As two artists who happen to also be librarians, these are the dialogues we want to spark and the questions we pose through Rule N° 5. We seek to engage library visitors with these questions not through an imposed narrative but rather via an interactive experience installed within a functioning library at New York University (NYU). In this site-specific installation, six different artworks are placed inconspicuously around the building, posing questions and connecting visitors to the ideas and workers located within their walls. The artworks invite library visitors to listen to the voices of the workers who make the living library and its collections possible, prompting them to reconsider a space they might not otherwise explore beyond the stacks.

While “Revisiting Ranganathan” cannot replicate the in-person experience of Rule N° 5—any digital representation will lack the tactile, sensory interaction and its intended context of being installed in an ever-changing, living, breathing library—this article surfaces what is, in fact, invisible in the exhibition’s living form, the story of the project’s creation, and makes explicit the underlying research, histories, and ideas that informed our work.

Process, Methodologies, and Collaborations

Rule N° 5 is an experience that lives at the intersections of public history, documentary, audiovisual anthropology, library science, and installation art. To create Rule N° 5, we incorporated a range of research methods. We recorded interviews, took deep dives into library science literature and trade publications, and conducted fieldwork. We toured our own workplace and observed people while at work. We wrote voiceovers and fictional scripts and commissioned original music. We tried to let go of our own assumptions and listen very closely to how others describe and define their work.

Some of the research underlying the project includes over forty hours of original recordings, including interviews and field recordings. These recordings were used as source material to create original sound compositions that help listeners better understand the inner workings of libraries. As noted by ethnographic researchers such as Gershon (2012), conducting and producing sonic ethnographies affords new ways of orienting listeners to an unfamiliar world and makes the collaborative processes inherent in many ethnographic research projects more explicit. By creating sound compositions to relay our research findings and ideas, we bring listeners into the world of libraries and convey more complex stories of library work by sharing the voices of many different librarians. Anthropologists Daza and Gershon (2015) discuss the ways that sonic ethnographies enable researchers to resist binaries and bring critical attention to overlooked aspects of everyday life. Considering the multiple and multilayered histories of libraries and the different kinds of library work and diverse perspectives about them, creating sound compositions enables us to shine a light on behind-the-scenes work and layer a variety of ideas and voices that embody the complex organism that is a living library.

From a card catalog that reveals the multifaceted yet hidden negotiations librarians make while organizing information to a whimsical radio where all the airwaves have been taken over by librarians, Rule N° 5 explores core questions of the profession in a way that is accessible to any listener. While the sound compositions may be listened to as individual pieces, Rule N° 5 is intended to be experienced as a whole and within the context of a working library. Our venue of publication—that is, an interactive active installation in a working library—is intentional. Taking inspiration from research in sensory ethnography (Howes 2003; Pink 2015), Rule N° 5 intervenes in traditional written academic research to surface and better convey the material and sensory aspects of often overlooked (and sometimes very dirty!) library work. The installation engages multiple senses and encourages visitors to make their own meanings of the library by literally grasping, hearing, and seeing how different information technologies and individual efforts of library workers impact what is saved and how it is discoverable. We carefully considered how visitors would interact with each artwork and how to best communicate our ideas and the points of inquiry that informed our work. As listeners open doors and drawers, plug in, and push buttons, they explore and contemplate what it means to collect the world’s knowledge, preserve the past, and shape the future.

In order to create such an interdisciplinary work, we worked in a collaborative fashion. Rather than a solo or even co-authored work, this co-creation was made in concert with a much larger community who lent their voices, time, and talents to the project. While we are the artists that drove the vision and concept, we collaborated with talented artisans to bring our ideas into the physical world.

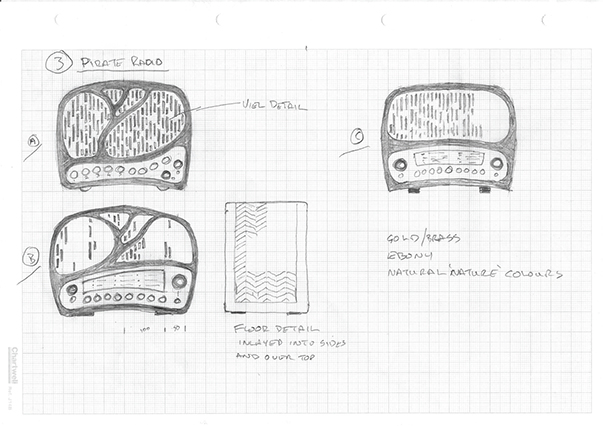

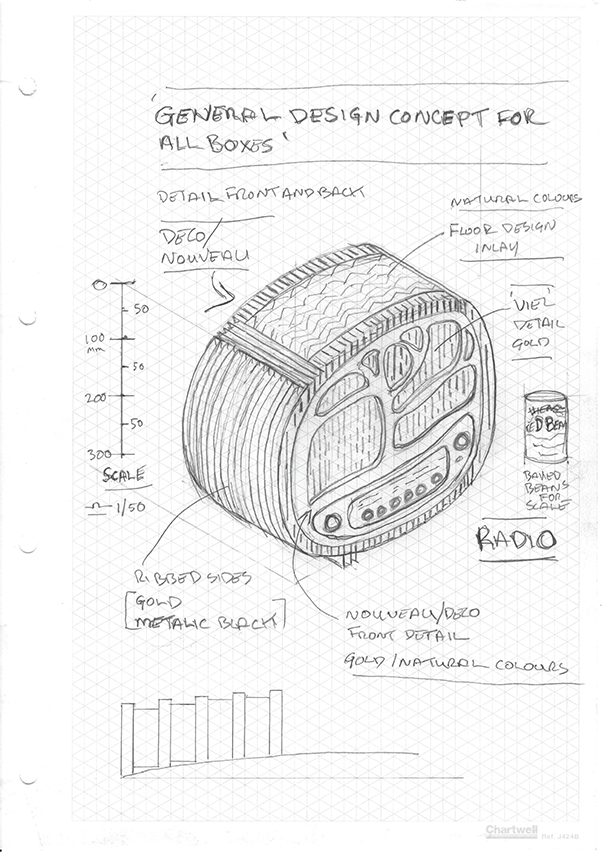

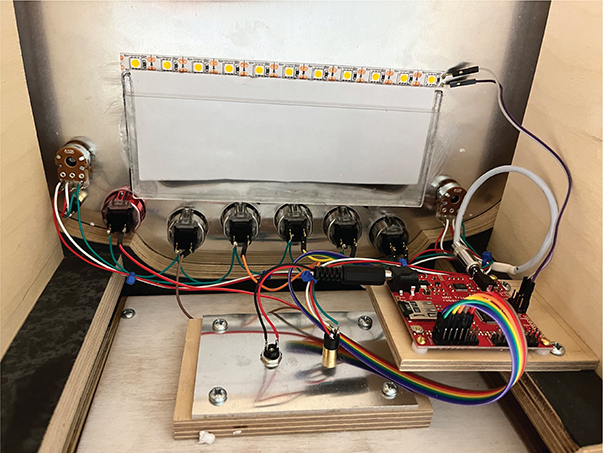

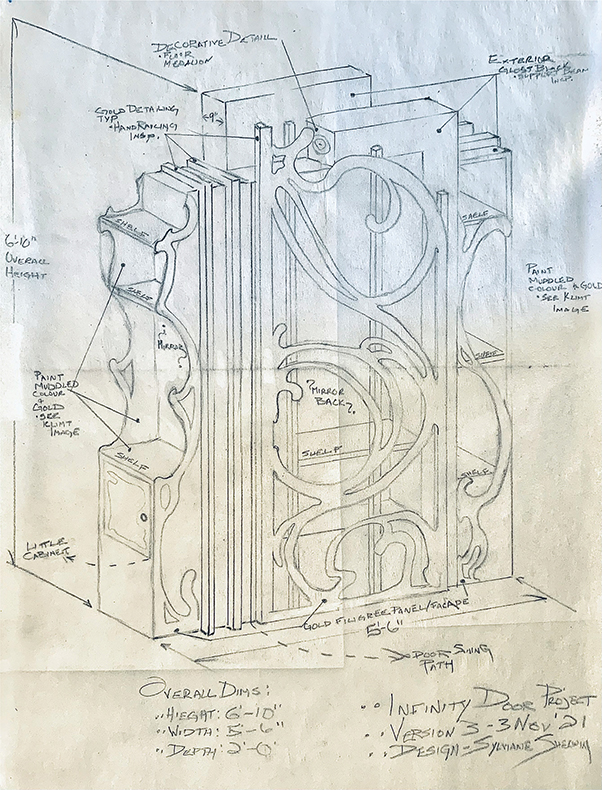

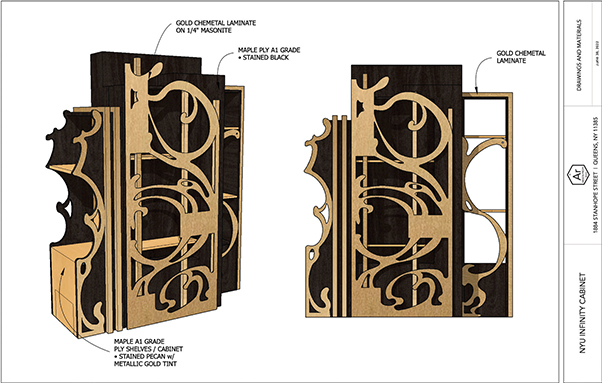

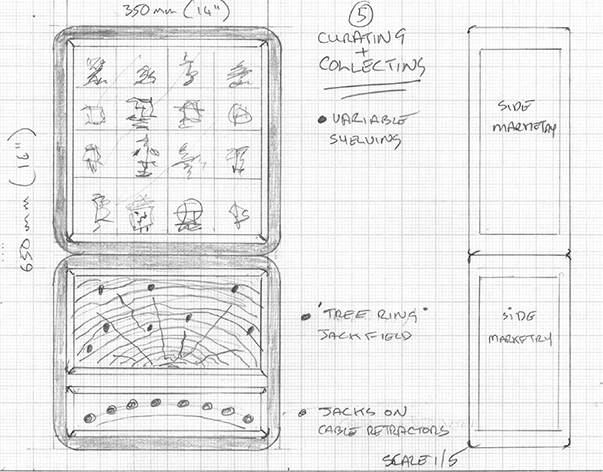

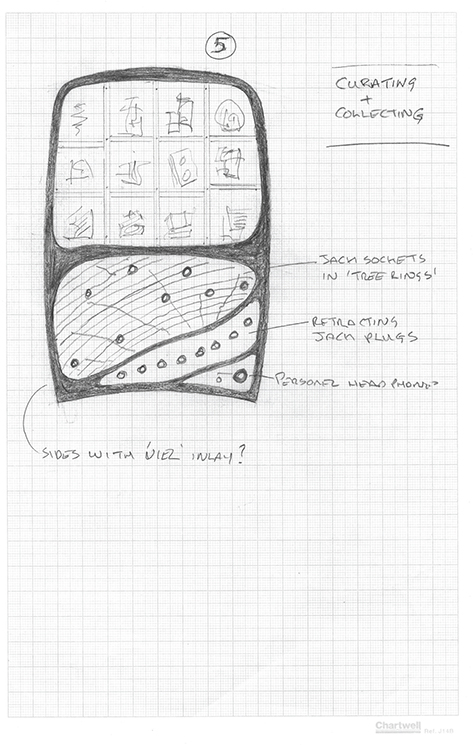

To design the physical artworks, we researched historical library furnishings and information technologies, architectural styles, and interaction designs. Once our ideas were clear, we shared them with Paul Gregory, a sound engineer and carpenter, and Jon Tipler, an audio technologist, who beautifully brought five of our whimsical ideas to life. Gregory shared multiple rounds of sketches, adding his own design elements before beginning to build each artwork (see Figures 1, 2, 3, 12, 13, 19, and 21). We decided how we wanted playback to function and discussed our ideas with Tipler, who then employed his skills to create the desired interactions (Figure 4). To create the artwork Infinity, we worked with scenic designer Sylviane Sherwin, who drafted the initial design (Figure 5) based on our ideas, which we communicated through a dollhouse-sized prototype (Video 1). A prop house in Brooklyn used Sherwin’s sketch to create a CAD file of the design (Figure 6) and fabricate the piece (Figures 7, 8). Finally, we also collaborated with sculptor Takashi Tateoka to create twelve custom miniatures that are housed within the artwork Curating & Collecting.

Figure 1. Early sketch renderings of Radio with different facades incorporating the “Pixel Veil” scaffolding of NYU’s main library and a tree motif.

Figure 2. Final design sketch for Radio with patterns that recall the NYU’s main library’s iconic marble tile floor pattern, now hidden under carpet after a recent library renovation, and the “Pixel Veil” atrium scaffolding with a can of beans for scale.

Figure 3. The realization of the artwork Radio with interactive facade.

Figure 4. The inner wiring for Radio includes a wav trigger audio playback device.

Figure 5. A sketch by scenic designer Sylviane Sherwin incorporates art nouveau influences and the architectural style of NYU’s main library into a vision for Infinity.

Video 1. Initial prototype for Infinity constructed with a dollhouse bookcase and door and fairy lights.

Figure 6. CAD renderings of Sylviane Sherwin’s drawing for Infinity.

Figure 7. Constructed in wood and metal plating, Infinity both blends in and stands out in the NYU’s main library atrium during the February 2023 opening event for Rule N° 5.

Figure 8. The door to Infinity opens to reveal a hidden doorway of lights and sound.

Below we describe the six pieces and companion exhibit that make up Rule N° 5 and the ideas that inform each artwork.

The Artworks and Companion Exhibit

Infinity

The first piece that visitors encounter is Infinity, a larger-than-life secret doorway. At first glance, the artwork appears to be an ornate bookcase, but upon taking a closer look, visitors discover a hidden door. Once opened, visitors hear an imagined sound of the library: a constant, humming presence or vibration that rings out across time. Peering inside, they experience a galaxy of twinkling lights: a portal into the possibilities that live within library collections.

On the inside of the door, headphones rest on an outstretched hand. Through the headset, listeners hear the sounds of Tibetan monks chanting alongside a series of voices in multiple languages welcoming them to the library. Another voice welcomes visitors and introduces them to the main concepts of the installation:

You are standing in a home, a home for ideas, curiosity, inspiration, and imagination. The thoughts of generations linger here, awaiting to be reawakened in the minds of readers, listeners, viewers, dreamers. What stories are missing? What might people ask of these materials and how might these collections reply? This library is one of hundreds of thousands of libraries, each with their own stories. Who brings them to life? Who can access their information? Who decides what lives within their walls? What is this living creature, this forest of thoughts? As you travel through the library, you may encounter other objects like this one, which are designed to help you explore questions of invisible labor, access, knowledge organization, and ethics of memory institutions as they decipher what it means to collect and make available the world’s knowledge.

This introduction is intended to frame the entire experience as visitors explore the rest of the installation. The voice asks questions that we ourselves have about the labor we perform as librarians and the ideas we want visitors to explore alongside us.

Throughout this and our other compositions in Rule N° 5, sound design plays a major role in bringing listeners into the library and its collections. While sound design has been an essential component of feature films since the advent of sound cinema (Chion 2009, 2019), it has been regarded with suspicion in traditional observational ethnographic film (Kasic 2020). Our work is informed, in part, by traditional ethnographic research methods, but Rule N° 5 also takes creative license and incorporates sound design and other fictional elements to offer listeners what film theorist Catherine Russell might describe as the “more experiential, embodied, and aesthetic” found in what she calls “experimental ethnography” (2015, 27). In Welcome to the Library (Sound Composition 1), visitors hear voices and sounds of various technologies: a film reel flickers through a projector, a needle reads the grooves in a vinyl record, a camera snaps a photo, users rustle through card catalog drawers, a library worker scans an item. The track culminates in a slow build of humming sounds, sourced from library staff voices, offering an audible sense of the number of people that are needed to build and keep libraries alive and relevant. The library is indeed a living organism, made of and created by people, as one staff member shares. The hums then overlap, resonating as if transmissions from other times and worlds, audibly demonstrating how they might mingle and reverberate into the future. In this way, the sound design makes the world and materiality of library work audible while also evoking the treasures that live within the collections.

Sound Composition 1. Welcome to the Library.

Curating & Collecting

Curation is at the core of library work. As one librarian we interviewed shared, “there’s so much [to potentially collect], you have to make decisions, and decisions means you can’t take everything, and if you can’t take everything, then you’re not taking some things” (Belantara and Alpin 2023; see Sound Composition 2). While library visitors enjoy what libraries have to offer, do they ever consider what it is like for library workers to decide what to collect, what not to collect, and what to discard? Reports of public outcry over library weeding projects (Eberhart 2001; Kniffel 1998) and requests from academics or community members for libraries to accept large donations of materials without hesitation (Cooper 1990; Delmar 2019) demonstrate a lack of public understanding about collection development and the amount of work required to thoughtfully curate a growing library. In Curating & Collecting, Rule N° 5 invites listeners to consider the many facets of curatorial decision-making and labor.

Sound Composition 2. Curating & Collecting.

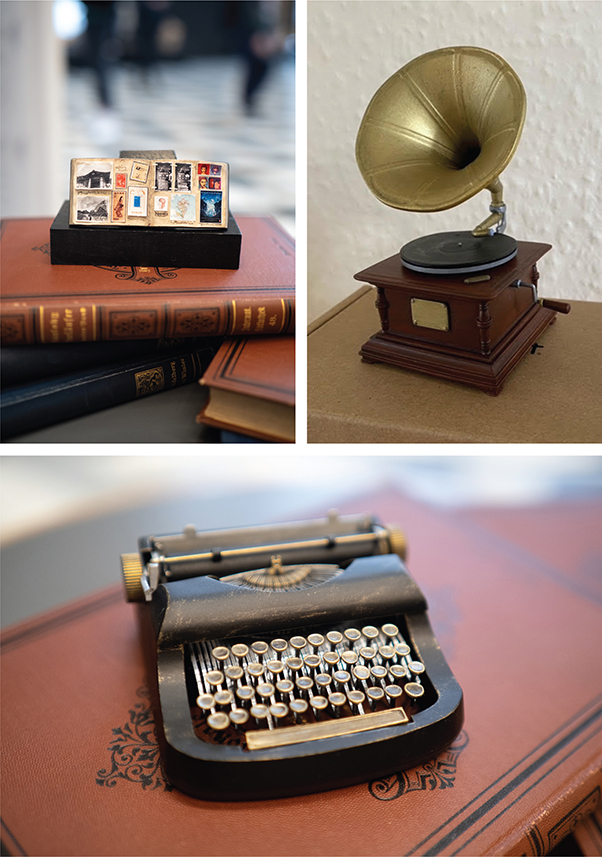

Curating & Collecting resembles a cabinet of curiosities that houses twelve miniatures representing information carriers and playback devices from early scrolls and volvelles to major innovations, including a gramophone, film camera and projector, typewriter, and external hard drives for digital storage brought to life through collaboration with sculptor Takashi Tateoka (Figures 9, 14, and 15). Beneath the curio cabinet are a series of plugs and cables inspired by a turn-of-the-century telephone switchboard built into an interface that resembles tree rings (Figures 10, 11). This switchboard design enables listeners to tune into the voices of different library workers as they make their mark on library collections and consider curatorial issues.2 By design, these voices are experienced among the display of miniature versions of the diverse material objects that libraries house, which include not only books but also scrolls, maps, phonographs, scrapbooks, film reels, VHS tapes, retro computers, and digital files (Figures 12, 13, 14). A sound composition that features curators speaking about their jobs plays against a continuous imaginary forest soundscape with sound effects that subtly reference books’ own forest of origin—the sounds of “trees creaking” are actually original recordings of creaky old book bindings housed in NYU’s Special Collections.

Figure 9. 3-D printed miniatures, designed and hand-painted by Tateoka, depict a scrapbook, a gramophone, and a typewriter.

Figure 10. Curating & Collecting: a cabinet containing miniature sculptures of various information carriers including a phonograph, retro computer, iPad with an Instagram feed, analog camera, typewriter, film reel, paper map, hard drive, books, and a scroll sit.

Figure 11. A visitor plugs into an audio jack built into a cabinet designed to appear as tree rings.

Figure 12. Early pencil design sketches created by carpenter Paul Gregory depict iterations of designs for Curating & Collecting.

Figure 13. Early pencil design sketches created by carpenter Paul Gregory depict iterations of designs for Curating & Collecting.

Figure 14. A Zoom screenshot of a 3-D miniature model of a gramophone. Belantara, Alpin, and Tateoka (pictured top to bottom) discuss the design.

Figure 15. Tateoka shows the finished miniature film projector and gramophone.

Video 2. Belantara interacting with Curating & Collecting cabinet.

Explore Curating & Collecting online.

Cataloging & Classifying

In Cataloging & Classifying, we consider the impact that knowledge organization practices have on how people search and how things are remembered. Without catalogers, library collections would be next to impossible to decipher. Cataloging workers are expected to adhere to strict rules and standardized controlled terms when describing library materials. Cataloging requires not only technical knowledge but also an engaged practice in the scholarly art of description. A cataloger’s task is to create meaningful guideposts that ensure materials can one day be found and accessed. The daily influx of new materials entering the library means that catalogers must be not only accurate and thoughtful but also swift. The magnitude of this work is often difficult for people outside of libraries to fathom, as is its political dimension. The organization and description of knowledge is not neutral, and the classification systems and standardized vocabularies used by catalogers reflect and uphold existing social, cultural, and political biases. As Chris Bourg explains, library “classification schemes are hierarchical, which leads to the marginalization of certain kinds of knowledge and certain topics” (2018, 458) and perpetuates the dominance of others. This inequity is exacerbated by the biases embedded in library technologies, which are “often gendered and/ or racist, frequently ableist, and almost always developed with built in assumptions about binary gender categories” (Bourg 2018, 460). As a library’s digital holdings begin to outnumber physical materials lining its shelves, Bourg (2018) notes that “the choices [libraries] make about how our technologies handle metadata and catalog records have consequences for how existing biases and exclusions get perpetuated from our traditional library systems into our new digital libraries” (2018, 458). Catalogers must contend with these systems and technologies on a daily basis, engaging in invisible critical labor that impacts how materials can be searched for and found.

However, an average library visitor knows little about the work catalogers do or what is at stake. Cataloging & Classifying calls visitors’ attention to this essential work while also engaging them in conversations around the problems with universalizing classification and descriptive systems.

The artwork resembles a traditional library card catalog, referencing an early library technology that impacted the development of modern computing systems (Krajweski 2011). By opening each drawer, visitors can hear one of two different sound compositions (Figure 16).

Figure 16. A visitor wearing headphones flips through the printed cards inside a custom-made card catalog drawer.

Video 3. Visitor interacting with the Cataloging & Classifying card catalog.

One drawer activates Sounding the Radical Catalog (Sound Composition 3), a composition that reveals the hidden negotiations embedded in library catalog records. Originally produced as part of the research project Catalogers at Work (Belantara and Drabinski 2022a), Sounding the Radical Catalog provides a short and accessible overview of what cataloging and classification are and amplifies catalogers’ voices as they struggle with the constraints of normative library systems. Numerous scholars have discussed the biases embedded in standardized classification systems (Higgins 2016; Yeh and Frosio 1971; Billey, Drabinski, and Roberto 2014; Berman 1971) and the importance of inclusive description practices (Perera 2022; Haugen and Billey 2020), but Sounding the Radical Catalog makes the hidden process of cataloging and counter-narratives that are otherwise invisible in published catalog records audible. Rule N° 5 builds on the original sound composition by adding sensory components that deepen the understanding of and engagement with these topics. When visitors open a card catalog drawer, they see a set of discarded catalog cards. The catalog cards include librarian marginalia and are interspersed with photographs of catalogers’ working stations and the tools they use. As visitors flip through these cards, each in themselves a representation of catalogers’ labor, they catch a glimpse of the behind-the-scenes work that enables discovery of their favorite library items.

Sound Composition 3. Sounding the Radical Catalog.

While cataloging is complex, we also wanted to reflect the pleasures of this work. In Belantara and Drabinski’s “Pleasure and the Practice of Classification” (2022b), they discuss that while many might think of cataloging as boring, monotonous work, trained cataloging workers themselves find their work to be rewarding and enjoyable. Catalogers relish the challenge of description and tracking down difficult-to-find bibliographic details. They find satisfaction in creating comprehensive catalog records that surface invisible labor by including credits that are not always on record and in describing materials in accurate, meaningful ways (Belantara and Drabinski 2022b). With these ideas in mind, we recorded a conversation with catalogers in which they shared what brings them the most joy. One revelation was just how many catalogers love listening to music while working. To create the sound composition The Joy of Cataloging, excerpts from their interviews were thematically edited and mixed over music that not only reflects the diversity of their musical tastes but also sonically conveys the emotional and material aspects of cataloging work itself, such as the feeling of “going down a rabbit hole” and trying to make a dent in an endless backlog of materials.

Explore Cataloging & Classifying online.

Radio

The “shusher.” The “gatekeeper.” The “bookish recluse.” Persistent stereotypes of librarians influence public perceptions and understandings of the profession, often not for the better. The stereotypical image of librarians as outdated and irrelevant is increasingly at odds with the dynamic roles librarians play in the digital age. To be sure, this gap between perception and reality is a critical issue for the profession’s future. But, in some ways, positive librarian stereotypes, such as a love for books, a willingness to go above and beyond for their patrons, and an unwavering commitment to information access, often remain strikingly true. While the librarian stereotype has been considered in professional literature, especially in recent years (see, for example, Wilson 1982; White 2012; Katz 2013; Pagowsky and Rigby 2014; Steffy 2015), our objective is to bring a new dimension to the scholarly debate through an inventive, multimedia framework. We tackle these sticky, persistent librarian stereotypes most especially through Radio, a bespoke vintage wooden radio that plays back five unique radio stations.

These, however, are not just any radio stations: each push button plays a different radio broadcast listeners might hear if librarians pirated all the airwaves and reimagined their content. From a whimsical top music countdown show à la famed radio disc jockey Casey Kasem to a talk and dedication show inspired by the highly syndicated Delilah, we invite listeners to laugh along with us as we reaffirm and dispel age-old stereotypes in fun and silly ways. The topic of stereotypes is even addressed directly in a talk radio station adapted from a real life library rock-n-roll radio show that airs on WREK Atlanta, Lost in the Stacks.3 Through both form and content, Radio is also an intentional nod to all the creative librarians out there, many of whom made original tracks or library-themed parody cover songs, from Lady Gaga to Prince, featured on our radio stations.

Radio considers not just the people in the libraries but also the materials themselves, which have lives of their own. What do they do when the building closes? What do they think about while waiting for someone to use them? One of our broadcasts, Library Alive (Sound Composition 4), provides some insight. Hosted by Terry Glass, the show takes its inspiration from Radiotopia’s Everything Is Alive podcast, an interview show with inanimate objects as the guests, but with a library twist. Fake advertisements are interspersed between the library object interviews with a stapler, a catalog record, and an artist book made out of Kraft Singles cheese slices. With librarian humor, these sponsor messages provide commentary on everything from the bias in library systems, as in the advert for the Chicano Thesaurus, to the hidden aspects of maintaining a library, such as the many invisible book repairs alluded to in a commercial for “Biblio Bliss: The Spa for Well-Loved Library Materials.”

Sound Composition 4. Library Alive.

Windows into Library Work (an Exhibit Within the Exhibit)

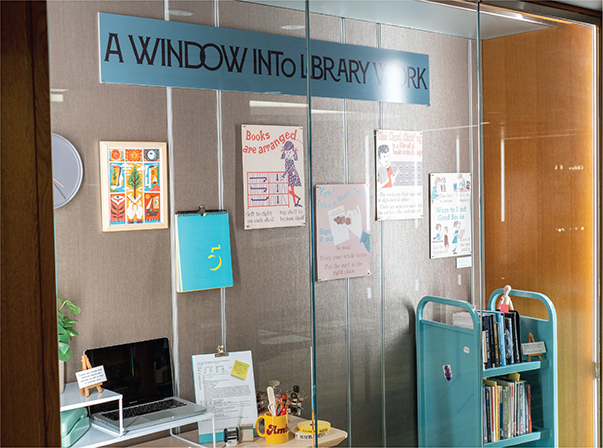

In addition to the six artworks featured in Rule N° 5, we also curated a companion exhibit to complement the sound compositions and interactive artworks. Composed of three vitrine cases and one large display case (Figure 17), Windows into Library Work is a deeper dive into some of the many issues we explore throughout Rule N° 5.

Figure 17. A view of A Window into Library Work, a fictitious library work office.

Library workers’ contributions are often underrecognized (Seale and Mirza 2019), likely—at least in part—because their labor is often invisible, and librarians have been trained to work quietly in the background in service of others (Settoducato 2019). In A Window into Library Work, we make visible the countless hours of work that often go unseen by the publics that libraries serve. A fictional librarian workspace is set behind glass and recalls a zoo enclosure, natural history museum exhibit, or shop window. Inside, one finds vintage library posters, a carefully curated book cart, and a desk full of library accessories from different eras, including a laptop and stamp carousel turnstile. Each item inside this fictitious office space represents some of the work that is often taken for granted . . . unless it is not happening (Figure 18).

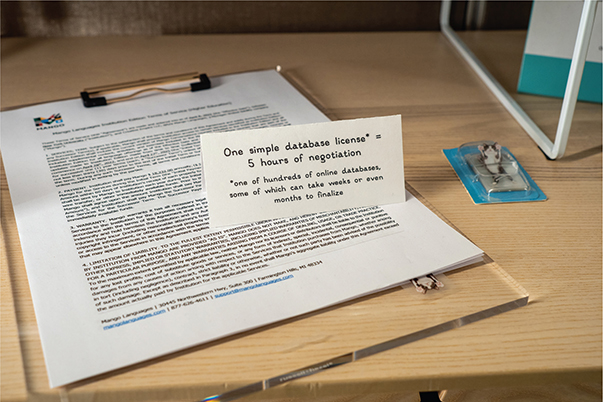

Figure 18. A card set on the top of an electronic database license agreement lets visitors know that negotiating this license took about five hours, a relatively fast process for database licenses.

Video 4. The Librarian (1947), Holmes Burton Films, courtesy of the Prelinger Archives.

In the companion exhibit, we also explore various aspects of the profession, including historical professional qualifications, librarian attributes and stereotypes, and the many rules library workers are expected to adhere to. From the outset, librarians have been required to learn and follow many rules and to exhibit particular personality or physical traits, both explicit and implied, such as politeness, helpfulness, and whiteness (Garrison [1979] 2003; Wiegand 2024). Some of the strict standards and rules within the profession are exemplified in the display. It includes The Library Assistant’s Manual (Koch 1913), which outlines desired librarian personality traits; a training guide called Patrons Are People: How to Be a Model Librarian (Minneapolis Public Library Staff 1945); and an example of a special form of penmanship known as Library Hand (Graham 1977). These documents illustrate the often chauvinistic, puritanical, and racist perspectives that underpin the early foundations of librarianship and impact the field today.

In the next display case, we also acknowledge that alongside ongoing racism and discrimination in the field, there is also a rich history of grassroots dissent, reform, and resistance in libraries. Library workers have challenged biases embedded in library practices, organized for better pay and working conditions, and have held the field accountable to its professed values in myriad ways. For instance, librarians have pushed back against standard classification systems like the Dewey Decimal Classification and the Library of Congress Classification by describing materials on their own terms. Notable forerunners displayed include librarian Dorothy Porter Wesley, who challenged and rejected racist library classification practices in the 1930s (Sims-Wood 2014; Helton 2019), and the collective efforts among library workers across institutions to create the Chicano Thesaurus in the 1970s (Castillo-Speed 1984). Also included are samples of the journal Progressive Librarian, published since 1990, in which librarians have pushed for social justice and exposed librarianship’s active and passive complicity in exploitative and oppressive systems. Examples of more recent, born-digital journals and DIY zines, such as LIS Microaggressions (Orozco, Fujita, et al. 2015; Orozco, Montenegro, et al. 2015), are also on display to exemplify the outlets where library workers join forces, build community, and address racism and many other -isms in the workplace.

Finally, a third case considers representations of library workers in the media. It contains stills from five films, representing a wide range of popular works from the 1950s to the 2020s, that illustrate some of the most prevalent ways library workers have been stereotyped as “sexy librarians,” bunned and bespeckled “shushers,” or even superheroes working behind the scenes. These stills are historically contextualized alongside Tevis and Tevis’s The Image of Librarians in Cinema (2005) for those wishing to explore the concept further. Alongside these fictional workers, viewers can also explore a full non-fiction film courtesy of the Prelinger Archives. Produced by Vocational Guidance Films, Inc. and Holmes Burton Films, the “Your Life Work” Series was a set of educational shorts from the early 1940s meant to inspire young post-depression workers into specific new careers. In The Librarian, a 1947 short from this series, a male narrator asks the viewer to consider, “Do you like people and do people like you? Do you like all kinds of people, the young, as well as the old people in all stations of life?,” while a middle-aged white woman enthusiastically guides young Jane through the ins and outs of the card catalog. With its outmoded “voice of God” narration and its oversimplified depiction of the profession, The Librarian reveals early examples of the feminized and belittling stereotypes that endure today.

Secrets

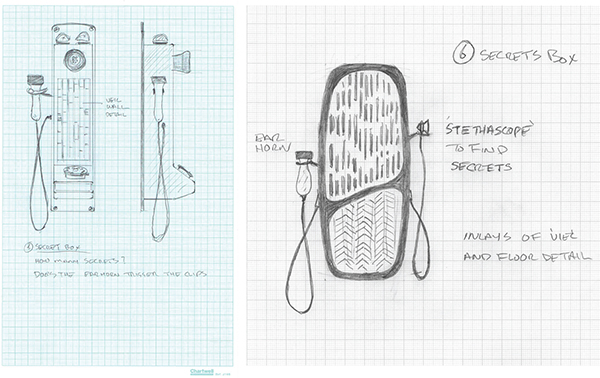

Libraries are full of secrets. Forbidden texts, answers to life’s greatest mysteries and latest scientific discoveries, love letters mistakenly left between the pages of books, archival items with restricted access. Libraries conceal and reveal secrets. Secrets acknowledges this presence and plays with the concepts of quiet and eavesdropping in the library. Curiosity is at the heart of libraries and of human imagination itself, so in designing this artwork it was important that visitors be inspired to awaken their own sense of curiosity and search for hidden sounds. As even the earliest of the design sketches and the final form of Secrets indicate, to find the library’s secrets in Rule N° 5 , visitors must lift the receiver to their ear and patiently move the stethoscope-like device across the body of the artwork to hear whispers, little-known facts, and confessions from within the library (Figures 19, 20). While the original secrets hidden within the artwork come from library staff, we wanted to open it up to house other kinds of library secrets too. Visitors are invited to share a secret of their own by calling a telephone number and leaving a voicemail. Tallulah, the host of the call-in confession program from Radio, greets callers. Select voice messages from callers may be placed inside Secrets in the future.

Figure 19. Early pencil design sketches created by carpenter Paul Gregory depict iterations of the design for Secrets from the earliest rendering, which most resembles an antique telephone, to a more whimsical final design.

Figure 20. An art nouveau–inspired artwork resembling an antique telephone mounted on a wall. A brass ear horn and stethoscopic listening device are attached. The front of the object features decorative elements inspired by the atrium of NYU’s main library.

Video 5. Belantara uses the brass ear horn and stethoscope-like device in Secrets to discover and listen to library secrets.

Impermanence

Libraries seek to preserve transmissions of thought, energy, and vibrations that echo into the universe for all time. Yet, despite preservation efforts, nothing lasts forever. The artwork Impermanence was inspired by these ideas, beautifully expressed in a letter by the poet Ocean Vuong (2022) at the time of the activist Thich Nhat Hanh’s transition:

Language and sound, as we know, are one of our oldest mediums of transmission. The root of the word “narrative” is “gnarus,” Latin for knowledge. As such, all stories are first and foremost the translation of knowledge. But not only that, they are the transmission of energy. And, as Thầy taught us, energy cannot die. As a poet, this is a truth I live with every day. Because to read a few lines of Gilgamesh or The Iliad or the Tale of Kiều, is to receive the linguistic energy of a mind working up to over four thousand years ago. In this way, to speak is to survive, and to teach is to shepherd our ideas into the future, the text is a raft we send forward for all later generations.

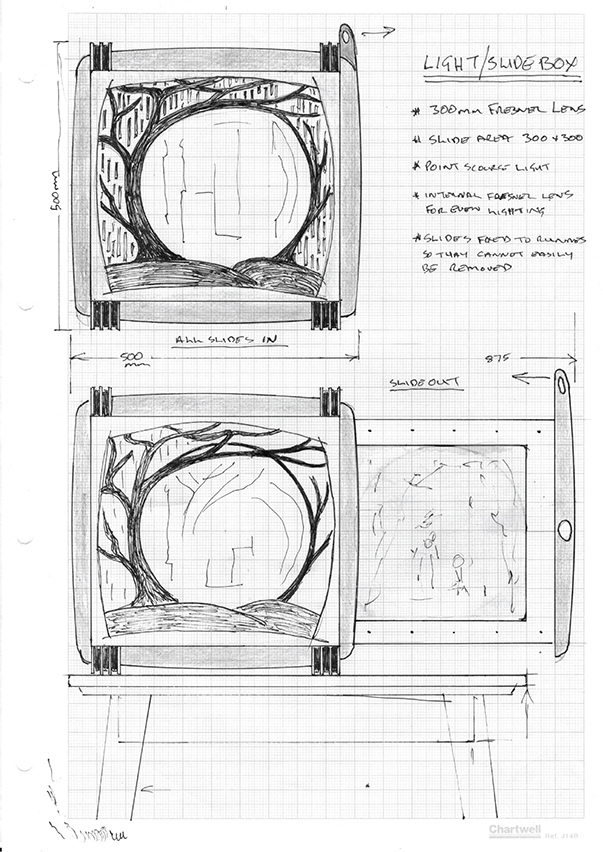

Sounds of whispering readers and a series of hanging lanterns made of discarded library audiovisual materials guide visitors to Impermanence, the final piece of Rule N° 5. The wooden artwork at the center of Impermanence is inspired by early glass slide viewers that were precursors to film and movie projectors (Figure 21). By interacting with the artwork to arrange and layer six slides (Figure 22), visitors experience the paradox of libraries: a sense of timelessness and forever—as captured in images from the James Webb Space telescope and some of the earliest cave paintings from Lascaux, France—in opposition to the impermanence of all things, depicted by mold, dust, faded handwriting, and outstretched hands amidst the viewer’s own fleeting reflection.

Figure 21. Final pencil design sketches created by Paul Gregory depict the interaction design of Impermanence.

Figure 22. A square wooden box is backlit, in the style of a “magic lantern” or early slide viewer. The slides, about the size of an LP record, layer to form an image composed of outstretched hands, dust and mold, stars, and handwriting on historic documents.

Access, Impact, and Resonance

While accessible to general public audiences, Rule N° 5 seeks to reach key target audiences of the NYU community: New York–area librarians and scholars. More largely, it is also intended to reach the worldwide community of library workers. To make the project accessible to as wide an audience as possible, the artworks feature specific hardware (knobs, buttons, and dials) usable for a wide range of visitors of different ages and abilities, all placed at accessible heights within spaces that are wheelchair accessible. QR codes direct in-person users to transcripts and closed-captioned videos. The project website employs the User Way widget to enhance accessibility.

Since its opening launch on February 27, 2023, the exhibit has been visited by library workers of the greater New York area via METRO Library Council, it has been integrated into museum studies class curricula, and each and every day it adds a touch of whimsy for the more than ten thousand daily visitors to NYU’s main library who pass by these curious and unusual objects scattered throughout the building.

Rule N° 5 has received national recognition in the library realm for its creativity, quality, and impact as the inaugural winner of the 2023 Innovation and Advocacy in Library History Award from the American Library Association Library History Roundtable and the recipient of the 2024 Outstanding Public History Project Award from the National Council on Public History.

Conclusion

Rule N° 5: The Library is a Growing Organism reflects, in the way all libraries ultimately do, the personal journeys of the people, culture, and time that created them. Our collective work reflects how there is no single narrative or way of knowing the library. While we posed many questions about the nature of libraries throughout the course of creating Rule N°5, ultimately we find that, despite all the changes in the past ninety years, Ranganathan’s fifth rule still rings true today. The library is and will remain a living organism: it is a manifestation, a continuously changing energy of minds. While many stories of libraries exist, Rule N° 5 adds to the conversation and incorporates audiovisual research methodologies that allow us to convey issues at the heart of the field in ways that can reach wider audiences both within and beyond the stacks. We shine a light on the many perspectives, messy processes, complex negotiations, and even the fun that goes on behind the scenes as we cultivate these living creatures and ensure they are well maintained for generations to come.

The library is an ongoing transmission that we, as library workers, hope helps humanity navigate uncertainty, cultivate new ideas, and create a better and more just world. It is a chorus of voices, composed of the generations of people whose works live inside their walls, in concert with the whispered voices of the people whose labor makes the collections available and the hushed tones of those who come in and seek out answers within them.

Acknowledgements

Rule N° 5 was made possible by the generous support of NYU Libraries, especially Dean H. Austin Booth. The authors would like to thank our many colleagues, past and present, who lent their voices to the work alongside many library workers from around the world. We want to acknowledge our key project collaborators, Paul Gregory and Jon Tipler, for their incredible contributions to bringing the project to life and Takashi Tateoka for lending his talents to the project as well. Each sound composition was carefully mixed by Michael Cacioppo Belantara and the project identity was created by Inaiah Lujan. We would also like to thank Nora Lambert and the NYU Photo Bureau for taking beautiful photos of the installation and Samuel Clegg for expertly filming some of the artworks for this publication. A full credit list can be accessed on the project website.

Ethics

The authors obtained permission from interviewees to include their voices and stories in Rule N° 5.

References

Belantara, Amanda, and A. M. Alpin. 2023. Rule N° 5: The Library Is a Living Organism. https://www.ruleno5.org/.

Belantara, Amanda, and Emily Drabinski. 2022a. “Working Knowledge: Catalogers and the Stories They Tell.” KULA: Knowledge Creation, Dissemination, and Preservation Studies 6 (3): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.18357/kula.233.

Belantara, Amanda, and Emily Drabinski. 2022b. “Pleasure and the Practice of Classification.” Library Trends 70 (4): 562–73. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/lib.2022.0018.

Berman, Sanford. 1971. Prejudices and Antipathies: A Tract on the LC Subject Heads Concerning People. Scarecrow Press.

Billey, Amber, Emily Drabinski, and K. R. Roberto. 2014. “What’s Gender Got to Do with It? A Critique of RDA 9.7.” Cataloging & Classification Quarterly 52 (4): 412–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639374.2014.882465.

Bourg, Chris. 2018. “The Library Is Never Neutral.” In Disrupting the Digital Humanities, edited by Dorothy Kim and Jesse Stommel. Punctum Books. https://doi.org/10.21983/P3.0230.1.00.

Castillo-Speed, Lillian. 1984. “The Usefulness of the Chicano Thesaurus for Indexing Chicano Materials.” In Biblio-politica: Chicano Perspectives on Library Service in the United States, edited by Francisco García-Ayvens and Richard Chabrán.

Chion, Michel. 2009. Film, a Sound Art. Columbia University Press.

Chion, Michel. 2019. Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen. 2nd ed. Columbia University Press.

Cooper, Ellen R. 1990. “Options for the Disposal of Unwanted Donations.” Bulletin of the Medical Library Association 78 (4): 388–91. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC225444/.

Daza, Stephanie, and Walter S. Gershon. 2015. “Beyond Ocular Inquiry: Sound, Silence, and Sonification.” Qualitative Inquiry 21 (7): 639–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800414566692.

Delmar, Nathan. 2019. “‘What Is Bought Is Cheaper Than a Gift’: The Hidden Burdens of Gifts-in-Kind and Policies to Help.” Legal Reference Services Quarterly 38 (4): 197–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/0270319X.2019.1696070.

Eberhart, George M. 2001. “Furor Erupts Over Chicago Weeding Program.” American Libraries 32 (9/10): 22, 24–25. EBSCOhost.

Garrison, Dee. (1979) 2003. Apostles of Culture: The Public Librarian and American Society, 1876-1920. University of Wisconsin Press.

Gershon, Walter S. 2012. “Sonic Ethnography as Method and in Practice: Urban Students, Sounds and Making Sense of Science.” Anthropology News. 53 (5): 5, 12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-3502.2012.53501.x.

Gershon, Walter. 2013. “Resounding Science: A Sonic Ethnography of an Urban Fifth Grade Classroom.” Journal of Sonic Studies 4. https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/290395/290396.

Gorman, Michael. 1995. “Five New Laws of Librarianship.” American Libraries 26 (September): 784–85.

Gorman, Michael. 2015. Our Enduring Values Revisited: Librarianship in an Ever-Changing World. American Library Association. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Graham, Lee Thomas. 1977. Library Hand: A Lost Art. Porcupine Quill Press.

Haugen, Matthew, and Amber Billey. 2020. “Building a More Diverse and Inclusive Cataloging Cooperative.” Cataloging & Classification Quarterly 58 (3–4): 382–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639374.2020.1717709.

Helton, Laura E. 2019. “On Decimals, Catalogs, and Racial Imaginaries of Reading.” PMLA 134 (1): 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1632/pmla.2019.134.1.99.

Higgins, Molly. 2016. “Totally Invisible: Asian American Representation in the Dewey Decimal Classification, 1876–1996.” Knowledge Organization 43 (8): 609–21. https://doi.org/10.5771/0943-7444-2016-8-609.

Howes, David. 2003. Sensual Relations: Engaging the Senses in Culture and Social Theory. University of Michigan Press.

Kasic, Kathy. 2020. “Sensory Verité.” In The Routledge International Handbook of Ethnographic Film and Video, edited by Phillip Vannini. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429196997.

Katz, Linda S. 2013. The Image and Role of the Librarian. Taylor and Francis.

Kniffel, Leonard. 1998. “Discord Over Discards Resurfaces in Philadelphia.” American Libraries 29 (11): 18. Gale OneFile.

Koch, Theodore Wesley. 1913. The Library Assistant’s Manual. State Board of Library Commissioners.

Krajewski, Markus, and Peter Krapp. 2011. Paper Machines: About Cards & Catalogs, 1548–1929. MIT Press.

The Librarian. 1947. Holmes Burton Films, courtesy of the Prelinger Archives.

Minneapolis Public Library Staff. 1945. Patrons Are People: How to Be a Model Librarian. American Library Association.

Orozco, Cynthia Mari, Simone Fujita, and Ann Matsushima Chiu. 2015. “LIS Microaggressions.” LIS Microaggressions 1 (1). https://www.dropbox.com/s/9ifn1ickikaeexc/LIS%20Microaggressions%20Zine%20Vol%201%20Iss%201.pdf?dl=0.

Orozco, Cynthia Mari, Erika Montenegro, Simone Fujita, and Elvia Arroyo Ramirez. 2015. “LIS Microaggressions.” LIS Microaggressions 1 (3). https://www.dropbox.com/s/php40mr90yp0lnn/LISMicroaggressions%20Volume%201%2C%20Issue%203?dl=0.

Pagowsky, Nicole, and Miriam Rigby. 2014. The Librarian Stereotype: Deconstructing Perceptions and Presentations of Information Work. Association of College and Research Libraries.

Perera, Treshani. 2022. “Description Specialists and Inclusive Description Work and/or Initiatives—An Exploratory Study.” Cataloging & Classification Quarterly 60 (5): 355–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639374.2022.2093301.

Pink, Sarah. 2015. Doing Sensory Ethnography. SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473917057.

Ranganathan, S. R. 1931. The Five Laws of Library Science. Madras Library Association.

Rubin, Richard E. 2015. Foundations of Library and Information Science. 4th ed. American Library Association. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Russell, Catherine. “Leviathan and the Discourse of Sensory Ethnography: Spleen et idéal.” Visual Anthropology Review 31 (1): 27–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/var.12059.

Seale, Maura, and Rafia Mirza. 2019. “Empty Presence: Library Labor, Prestige, and the MLS.” Library Trends 68 (2): 252–68. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2019.0038

Settoducato, Leo. 2019. “Intersubjectivity and Ghostly Library Labor.” In the Library with the Lead Pipe. https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2019/intersubjectivity-and-ghostly-library-labor/. Archived at: https://perma.cc/32K7-UHGY.

Sims-Wood, Janet. 2014. Dorothy Porter Wesley at Howard University: Building a Legacy of Black History. The History Press.

Steffy, Christina J. 2015. Librarians & Stereotypes: So, Now What? Crave Press.

Tevis, Ray, and Brenda Tevis. 2005. The Image of Librarians in Cinema, 1917–1999. McFarland.

Vuong, Ocean. 2022. “A ‘Love Letter’ for Our Community.” Thich Nhat Hanh Foundation. https://thichnhathanhfoundation.org/blog/2022/2/17/a-love-letter-for-our-community-by-ocean-vuong. Archived at: https://perma.cc/MK99-S62T.

Wiegand, W. A. 2024. In Silence or Indifference: Racism and Jim Crow Segregated Public School Libraries. University Press of Mississippi. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.18427139.

White, Ashanti. 2012. Not Your Ordinary Librarian: Debunking the Popular Perceptions of Librarians. Chandos Publishing.

Wilson, Pauline. 1982. Stereotype and Status: Librarians in the United States. Greenwood Press.

Yeh, Thomas Yen-Ran, and Eugene T. Frosio. 1971. “The Treatment of the American Indian in the Library of Congress E-F Schedule.” Library Resources and Technical Services 15 (2): 122–31.

Additional Works Referenced in Rule N° 5

Burns-Simpson, Shauntee, Nichelle M. Hayes, Ana Ndumu, Shaundra Walker, and Carla D. Hayden. 2022. The Black Librarian in America: Reflections, Resistance, and Reawakening. Rowman & Littlefield.

Cassidy, Kyle. 2017. This Is What a Librarian Looks Like: A Celebration of Libraries, Communities, and Access to Information. Black Dog & Leventhal.

Crilly, Jess, and Regina Everitt, eds. 2022. Narrative Expansions: Interpreting Decolonisation in Academic Libraries. Facet Publishing.

Dewey, Melvil. 1898. Simplified Library School Rules. Boston: Library Bureau.

Doubleday, W. E. 1931. A Primer of Librarianship: Being Chapters of Practical Instruction by Recognised Authorities. G. Allen & Unwin and the Library Association.

Gleason, Eliza A. 1940. The Government and Administration of Public Library Service to Negroes in the South. University of Chicago.

Gleason, Eliza Atkins. 1942. “The Atlanta University School of Library Service: Its Aims and Objectives.” The Library Quarterly 12 (3): 504–10.

Gunn, Arthur C. 1986. Early Training for Black Librarians in the U.S.: A History of the Hampton Institute Library School and the Establishment of the Atlanta University School of Library Service. University of Pittsburgh.

Hewins, Caroline M. 1891. “Library Work for Women: Some Practical Suggestions on the Subject.” Library Journal 16.

Jackson, Andrew P., Julius Jefferson Jr., and Akilah S. Nosakhere, eds. 2012. The 21st-Century Black Librarian in America: Issues and Challenges. Scarecrow Press.

Josey, E. J. 1970. The Black Librarian in America. Scarecrow Press.

Lankes, R. David. 2011. The Atlas of New Librarianship. MIT Press; Association of College & Research Libraries.

Lankes, R. David. 2016. The New Librarianship Field Guide. MIT Press.

Leung, Sofia Y., and Jorge R. López-McKnight. 2021. Knowledge Justice: Disrupting Library and Information Studies through Critical Race Theory. MIT Press.

Lewis, Alison M. 2008. Questioning Library Neutrality: Essays from Progressive Librarian. Library Juice Press.

McKinney, Cait. 2020. Information Activism: A Queer History of Lesbian Media Technologies. Duke University Press.

Mehra, Bharat. 2019. LGBTQ+ Librarianship in the 21st Century: Emerging Directions of Advocacy and Community Engagement in Diverse Information Environments. Emerald Publishing Limited.

Morrone, Melissa. 2018. Human Operators: A Critical Oral History on Technology in Libraries and Archives. Litwin Books.

Nauratil, Marcia J. 1989. The Alienated Librarian. Greenwood Press.

Neely, Teresa Y., and Jorge R. López-McKnight, eds. 2018. In Our Own Voices, Redux: The Faces of Librarianship Today. Rowman & Littlefield.

Nicholson, Karen P., and Maura Seale, eds. 2018. The Politics of Theory and the Practice of Critical Librarianship. Litwin Books.

Oliver, Amanda. 2022. Overdue: Reckoning with the Public Library. Chicago Review Press.

Ottens, William. 2020. Librarian Tales: Funny, Strange, and Inspiring Dispatches from the Stacks. Skyhorse Publishing.

Phenix, Katharine, Kathleen de la Peña McCook, and American Library Association Committee on the Status of Women in Librarianship. 1989. On Account of Sex: An Annotated Bibliography on the Status of Women in Librarianship, 1982-1986. American Library Association.

Quinn, Mary Ellen. 2014. Historical Dictionary of Librarianship. Rowman & Littlefield.

Sheridan, Gina. 2014. I Work at a Public Library. Adams Media.

Smith, A. Arro. 2017. Capturing Our Stories: An Oral History of Librarianship in Transition. Neal-Schuman, an imprint of the American Library Association.

Tharp, Shannon, and Sommer Browning, eds. 2018. Poet-Librarians in the Library of Babel: Innovative Meditations on Librarianship. Library Juice Press.

Winsor, Justin. 1878. “The English Conference: Official Report of Proceedings.” Library Journal 11 (5–6).

Footnotes

1. See, for instance, Gorman (1995) for a creative rewriting of the five laws and Gorman (2015) for a fuller history of the foundational impact of Ranganathan’s work.

2. The artwork’s tree ring motif was inspired by an interview with rare book librarian and curator Charlotte Priddle. Priddle shared her perspective that a curator’s role is akin to one of many rings on a tree, the collection itself being a tree that existed before and will continue long after any single curator’s tenure.

3. “Librarian Stereotypes” is adapted from Episode 408: “We Know Who We Are,” hosted by Charlie Bennett and Ameet Doshi, WREK, Atlanta, Georgia.