RESEARCH ARTICLE

Mapping for Reconnection: Place Name Documentation and the Atlas of Kanyen’kehá:ka Space

Rebekah R. Ingram

Carleton University

Kahente Horn-Miller

Carleton University

Indigenous place names contain knowledge of the landscape and encode unique perceptions of landscapes with which Indigenous Peoples have interacted for hundreds, often thousands, of years. However, many Indigenous place names have been lost as a result of colonization. Furthermore, many of these have been replaced with colonial place names, and their loss contributes to overall language attrition. In turn, the loss of language makes it difficult, or even impossible, to understand the concepts embedded within Indigenous place names that do remain in use. The documentation and conservation of place names is thus an important aspect of Indigenous language preservation and revitalization that can help facilitate reconnection with the language and the land. This paper outlines the Atlas of Kanyen’kehá:ka Space digital atlas project, an initiative that uses digital mapping to aid in the documentation and revitalization of the Kanyen’kéha (Mohawk) language through community participatory mapping of Kanyen’kéha place names and landscape-related language. It describes the initial stages of the Atlas of Kanyen’kehá:ka Space project, including its theoretical framework, the O’nonna model, and its community-based participatory methodology for digital mapping. It reports on a series of mapping workshops within three Kanyen’kehá:ka communities and shares initial findings and future directions for the project.

Keywords: participatory mapping; place names; Kanyen’kéha; Mohawk; language documentation

How to cite this article: Ingram, Rebekah R., and Kahente Horn-Miller. 2024. Mapping for Reconnection: Place Name Documentation and the Atlas of Kanyen’kehá:ka Space. KULA: Knowledge Creation, Dissemination, and Preservation Studies 7(1). https://doi.org/10.18357/kula.281

Submitted: 29 September 2023 Accepted: 4 October 2024 Published: 26 November 2024

Competing interests and funding: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Copyright: © 2024 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Introduction

Indigenous place names represent an important intersection between land, language, and culture. They may contain historical, social, or ecological knowledge of the landscape and encode unique perceptions of landscapes with which Indigenous Peoples have interacted for hundreds, often thousands, of years. However, colonization has put much of this place-based knowledge at risk. First, many Indigenous place names have become incomprehensible due to the imposition of colonial place names. As Yom and Cavallaro argue, the renaming of spaces using colonial languages and naming conventions is an act of linguistic displacement and colonization: “naming, or renaming, is an essential part of the colonisation process that reflects the asymmetrical power relationship between the colonisers and the colonised” (2020, 1). And second, while many Indigenous place names have been borrowed into, and may still be used within, non-Indigenous-language naming practices—in what is now called North America, for example, place names such as Quebec, Ontario, and Canada trace their origins to Indigenous languages (Ingram 2020)—the meaning of these names is not widely known because Indigenous languages have become less frequently spoken, in some cases to the point of endangerment or dormancy, due to colonial attempts at assimilation. In either case, the loss of the names themselves or the naming language, the knowledge carried within place names is also lost.

Given the interconnection between language, landscape, and culture, place names are an extremely important aspect of Indigenous language documentation, and mapping place names is, therefore, a way to reconnect people to their language and understandings of space following a disconnection due to colonization and colonialism. This paper outlines the Atlas of Kanyen’kehá:ka Space digital atlas project, an initiative that uses digital mapping to aid in the documentation and revitalization of the Kanyen’kéha (Mohawk) language through community participatory mapping of Kanyen’kéha place names and landscape-related language.1 Kanyen’kehá:ka (Mohawk) communities identify place names and their meanings, and the features that the names refer to, and add text and multimedia into a digital mapping database, reinvigorating the community’s knowledge of the landscape and their unique perceptions of those landscapes.

This paper will begin by outlining the background to the project, which includes place naming theory and how perceptions of place may differ across cultural backgrounds and environments. In the case of Indigenous place names, an intimate knowledge of the landscape is often entwined within the names used to denote specific locations. In this section, we also introduce the O’nonna model, the theoretical framework outlining the interrelationship between language, landscape, and culture that underpins the Atlas of Kanyen’kehá:ka Space project. Based on this model, we explain, with a focus on Kanyen’kéha place names, language, and culture, how the loss of place names is a disruption of this interrelationship and contributes to language attrition and loss. We then discuss the methodology used in the Atlas of Kanyen’kehá:ka Space project, including our decision to use the Nunaliit platform as well as a description of our participatory mapping approach. Finally, we summarize mapping workshops conducted within three Kanyen’kehá:ka communities using the Atlas of Kanyen’kehá:ka Space and conclude with initial findings and future directions of the project.

Background

Indigenous Place Names

Because of the amount of information that can be encoded within a place name, as well as its complements to other aspects of landscape and culture, place names mark an extremely valuable and rich semantic domain. Place naming is place knowing: place names carry knowledge of the landscape and what is done in specific places, knowledge that is passed from generation to generation as part of cultural expression. As Jordan explains, geographical spaces are cultural landscapes: a group of people “makes use of natural resources (offered by geographical space)” and also “reflects itself in [that] space, shap[ing] [the] space” and “creating a cultural landscape” that becomes part of the group’s cultural identity (2012, 117). A group lives in a space, uses what is available in the space, and elements of this space enter into the culture. Geographical space and culture, in turn, shape language, including place names, as a tool of cultural expression and intergenerational knowledge transmission.2

The types of place names assigned by different cultural groups will differ according to their perceptions of and relationships to those places. Indigenous place names are often descriptive, based on an intimate knowledge of the landscape. According to Stewart in Names on the Globe, descriptive place names are a category of “evolved” place names (1975, 5), which Randall defines as names that “originated . . . to identify features probably of significance to local inhabitants” (2001, 6), i.e., physical or environmental features of significance. What Stewart refers to as “bestowed” names (1975, 5) are given as “a conscious act of naming” (Randall 2001, 6) and are often tied to colonial naming conventions such as naming a place for a specific person in order to praise or recognize them (e.g., Washington) or in recognition of a former homeland (e.g., Plymouth) (Randall 2001). In contrast, descriptive place names describe some physical or environmental aspect of the landscape that is of significance to the namers, which may include cultural practices and beliefs (Ingram 2020). For example, the Lule Saami language utilizes one system of place naming relating to bears, “a sacred animal for the Sami. These associations of place names are often linked to a physical resemblance between the features of the landscape and the objects designated by the names. They can also be connected to narratives that can explain these specific land features” (Cogos et al. 2017, 46). Stephen C. Jett outlines further the breadth of information that can be contained in, and is imparted by, place names, stating that these names “may also convey important information concerning cultural beliefs and values, folklore, ethnography, economics, and history. Placenames also function as mnemonic devices that may facilitate communication, travel, resource-finding, and mythological memory, and as such are highly charged linguistic symbols” (2001, personal communication).

Descriptive place names may also contain linguistic terms which are unique cultural conceptualizations and understandings of landscape and waterscape features acquired over generations. Turk et al. (2011) refer to the way that different cultures perceive, categorize, and conceptualize their physical landscape and environment, and the way that these are reflected in language, as ethnophysiography. Many ethnophysiographical terms are used in descriptive place names, and these terms may be used for hundreds of years, carrying the knowledge of the landscape forward through generations. As such, they are an important part of descriptive place names. For example, in the Yindjibarndi language, an Indigenous language spoken in the arid interior of what is today called Australia, the term wundu describes a place that is referred to in English using terms like river and creek (Mark et al. 2010). However,

A wundu is an almost-always-dry place where water occasionally flows, while the words ‘river’ and ‘creek’ refer to features normally composed of flowing water and which necessarily have beds and banks. . . . When water does flow in a wundu such as Dawson Creek, usually during heavy rains . . . the flood (of water) is referred to as a mang-kurdu. . . . In both cases, there is a name for the water when it is there, distinct from the channel in which it lies or flows. (Mark et al. 2010, 32)

The terms wundu and mang-kurdu are specific conceptualizations of a landscape unique to that particular location, which have been encoded into linguistic terms with very specific meanings that are also unique to that location and to the group of people who use it. The loss of Indigenous place names, many of which include significant ethnophysiographical terms, or the loss of the meanings of these place names through language attrition, thus entails the loss of unique understandings of the landscape. As the next section will explain in the context of the O’nonna model, the loss of this knowledge is part of an ongoing cycle in which language loss exacerbates disconnection from culture and the land.

Theoretical Framework: The O’nonna Model

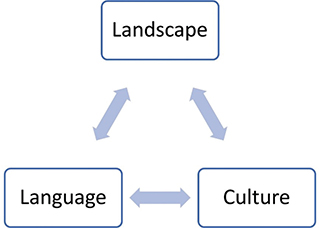

The study of place names requires a theoretical framework that attends to the interrelationship between landscape, culture, and language. For the Atlas of Kanyen’kehá:ka Space, this framework is the O’nonna Three-Sided Model (Ingram 2020; see Figure 1), which outlines the interconnection of these three elements and the co-related impact of the loss, through colonization, of one of them. If one element is severed from the triad, the connection between the other two elements will also be severed. Outlined in Ingram (2020), this theory and model was first called O’nonna by Francis Ateronhiata:kon Boots of Akwesasne. Ateronhiatakon was a first-language speaker of Kanyen’ké:ha who taught the language and history and was active within the Kanienkehaka Kaianerehkowa Kanonsesne longhouse at Akwesasne. As he was also a personal friend to both authors, we consider it an honour that he imparted this name on the theory and model before his death in 2023.

Figure 1: The O’nonna Three-Sided Model first introduced in Ingram (2018), revised in Ingram (2020).

The most obvious and direct mechanism of colonization is dispossession of and physical displacement from the land. Farrell et al. (2021) estimate that there has been a 98.9 percent loss of Indigenous land possession since pre-colonial times, and some Indigenous groups are entirely without a land base due to a lack of legal recognition by state, provincial, and federal governments. The present-day land base of Indigenous Peoples averages 2.6 percent the size of their estimated area prior to contact. Direct loss of Indigenous cultural knowledge and language can also be traced to federal policies that forbade cultural practices such as pow wows and potlaches3 and forced Indigenous children to attend residential schools.4

The O’nonna model attempts to capture the more indirect results of colonialism by demonstrating how a disconnect from landscape, culture, or language will create a larger disconnect between all three. The displacement, removal, or destruction of the land also entails a loss of the practices taking place on the land because accessing the natural resources necessary for the practice of culture is not possible. This disconnection from the landscape also means that the language associated with those cultural practices cannot be used within the appropriate contexts, and the disuse of language associated with specific cultural acts, including acts identified with and associated with place names, contributes to language attrition (Paradis 2007).5 Without the opportunity to use language in context (i.e., on the land), specialized vocabulary, terminology, and grammatical structures are less likely to be transmitted to the subsequent generation of language speakers—or if they are, only in an impoverished form, disconnected from the Indigenous Knowledge they should convey. This in turn leads to erosion of language over generations; as each generation of children acquires the language, there is simply less of the language to learn because the vocabularies and grammatical structures used in specialized activities have not been passed down to the previous generation due to the inability to carry out those activities. For example, if one cannot access the materials on the landscape to make a basket, one cannot teach how to make a basket, nor teach the linguistic elements that are involved in communicating how one makes a basket. The language of basketry, therefore, is not used, children do not acquire the vocabulary, terminology, or grammatical elements of the semantic category of “basket making,” and those elements may become dormant. In this regard, children will acquire an impoverished form of language without the full spectrum of vocabulary and specialized linguistic structures intrinsic to their mother tongue; as a result, they are constrained in use to the impoverished form and are more likely to utilize a second language such as English or French, a phenomenon known as interference. For each semantic category that cannot be practiced due to a lack of access to the landscape (for example, basketry, foraging practices, fishing, traditional agriculture, etc.), the language of that semantic category becomes less used and therefore less likely to be passed on to children. Thus, impoverishment is cyclic in nature and feeds back into the next generation of language learners, who will acquire an even less linguistically rich version of the language, leading to more interference and continuing the cycle. Without the full range of linguistic structures, speakers are increasingly more likely to shift to other languages.

With regard to place names, this can lead to concretization: if a name does remain in use, it may become solely a marker for the place rather than a semantically complex term containing meaningful information about it as a geographical and cultural space.6 The loss of language makes it difficult, or even impossible, to understand the concepts embedded within the names. In this case, the Indigenous Knowledge of the physical environment encoded within the language is lost, and communities are alienated from cultural practice; then, in an ongoing cycle, the ability to use the language is further compromised, so speakers continue to acquire an impoverished form of the language and may be forced to use a different language when talking about the landscape. The implications of this language shift are even further-reaching in that language encoding Indigenous Knowledge and Traditional Environmental Knowledge may not translate effectively or at all into other languages. According to Hill, translations “cannot make up for the concepts that exist in one culture but not in the other . . . due to the limitations of translating between languages that are based within very different world views” (2017, 16). Knowledge of the landscape and environment is lost with the language, which in turn affects interaction with that environment.

However, place names also represent the endurance of a language and the people who speak it since “in their capacity as synchronic and diachronic expressions attached to smaller or bigger places, place names are a vital part of everyday language as well as of the individual and collective memory and collective identity” (Helleland 2012, 96). The Indigenous place names still used today refer to particular locations in the present; however, they are also a legacy of the past, associated with the history of places both on a small scale (as individual locations) and on a large scale (the history surrounding all of what is today called North America, for example). Place names are signposts through time as well as through space; they connect an individual to the present and the past, as well as to all those who have knowledge of, or connection with, that place in the present and the past. Even if a language becomes dormant, Tsunoda adds that “it is possible to say that a language is alive as long as it survives in place names or the like (Veri Farina, p.c.)” (2006, 41). As long as speakers of the naming language remain, and the place name approximates its original pronunciation or can be traced with documentation to an approximate original pronunciation, the information contained within the name also remains. As the O’nonna model illustrates, the revitalization of Indigenous languages can help recover the knowledge contained in language, fostering reconnection with cultural practices and the land. The documentation and preservation of place names through methods such as linguistic analysis and community-based participatory digital mapping represents a unique opportunity as the starting point of conservation and revitalization.

Researching and Documenting Kanyen’kehá:ka Place Names

Kanyen’kéha is the language of the Kanyen’kehá:ka, part of the Northern Iroquoian branch of the Iroquoian language family (Julian 2010) and the most widely spoken Iroquoian language in Canada (Statistics Canada 2017). The federal census reported an ethnic population of 24,000 with 2,350 speakers. Sixty-seven percent of speakers were located in Ontario and 29 percent in Quebec (Statistics Canada 2017). A 2014 survey by the Mohawk Council of Kahnawà:ke and the Kanien’kéha Onkwawén:na Raotitióhkwa Language and Cultural Centre on the status of Kanyen’kéha in Kahnawà:ke reported that 27 percent of the 376 people surveyed identified as non-speakers, 44 percent as beginners, 16 percent as intermediate, and 12 percent as advanced/fluent speakers (Mohawk Council of Kahnawà:ke 2014). Revitalization programs such as Kawenní:io/Gawení:yo Private School in Six Nations and the Akwesasne Freedom School in Akwesasne are working to reverse language endangerment through immersion or near-immersion programming. Language revitalization efforts in other Mohawk territories continue this resurgence.

It is important to note that, according to oral history and archival sources, the traditional territory of the Kanyen’kehá:ka was centred around the Mohawk River valley near present-day Albany, New York, providing a direct route between Kanyen’kehá:ka territory and the Hudson River, the Atlantic Ocean, and the major coastal ports of the colonial New Netherlands, including New Amsterdam (now New York City) (Ingram 2020). The Kanyen’kehá:ka regularly moved villages every ten to twenty years for natural resource management, to allow agricultural areas to fallow, and new villages were often established due to increases in population or to avoid conflict, or for better access to trade opportunities and hunting grounds (Ingram 2020). The villages of Oswegtchie and Akwesasne were both a result of this practice. In 1664, the New Netherlands colonies were ceded to the British, and a 1665 treaty with the French led to the establishment of mission villages and trading posts such as Kahnawà:ke and Kanehsatá:ke, both located in what is today called Quebec, to facilitate trade and conversion to Christianity (Parmenter 2010). When the American Revolutionary War began in 1775, the Kanyen’kehá:ka allied with the British, with whom they had established an alliance (Berleth 2009, 242). As a result of this alliance, the Sullivan-Clinton campaign of 1779 sought to completely subdue the Kanyen’kehá:ka and other allied Indigenous Nations by effectively destroying all villages and fields in the Mohawk River valley (National Park Service 2022). This compelled many Kanyen’kehá:ka to relocate to British Canada for their survival (Berleth 2009). As such, the Kanyen’kehá:ka have been at least partially removed from their traditional territory and, consequently, the landscape associated with many of their cultural practices, a disconnection of the elements of O’nonna. The language has also become endangered. As a result, language related to the landscape is vulnerable to attrition, and the place-based knowledge embedded in the language is at risk.

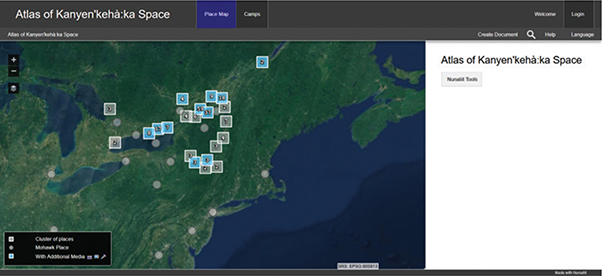

Figure 2: A screenshot of the Atlas of Kanyen’kéha Space as of September 2023.

In 2014, to help document and preserve endangered Kanyen’kéha place names and knowledge, Ingram and members of the community of Akwesasne began a project researching the folk etymologies and possible meanings of the many Kanyen’kehá:ka (Mohawk) place names throughout those places found in what are today called New York, Pennsylvania, Ontario, and Quebec. In 2015, the project became a PhD dissertation in collaboration with members of the Kanyen’kehá:ka communities of Akwesasne, Kahnà:wake, and Kehntè:ke (Tyendinaga) with Kahente Horn-Miller (Kahnawà:ke) serving as an advisor. Completed in 2020, the dissertation included a grammatical analysis and an examination of the meanings of contemporary and historical names. Drawing on archival materials (maps, travel journals, government documents that encoded Indigenous place names within a geographic area approximating the Kanyen’kehá:ka homeland) and interviews with Kanyen’kéha speakers from within the communities, the dissertation provided an overview of Kanyen’kehá:ka naming conventions and outlined the proposed meaning of eighty-nine Kanyen’kéha place names. Ingram presented these names to Kanyen’kéha speakers and community members, who interpreted each of the names and provided context and explanation regarding cultural, historical, or landscape elements found within them.

This community-led process is important because those who come from outside of a culture may misunderstand the motivation for a place name, instead inadvertently ascribing a cultural, historical, or ethnophysiographic value from within their own culture (Ingram 2020). Such was the case with much early research on Indigenous place names. Those who undertook early place name research focusing on names of North American Indigenous origin sometimes had little or no formal training in linguistics (which was not considered a “formal” field of study until around the 1920s) or its predecessor, philology. Those who did have a background in language studies were often unfamiliar with the structures of North American Indigenous languages, many of which have extremely complex systems of word formation relying on the extensive use of prefixes or suffixes and differ significantly from colonial languages such as English and French. The result, according to Afable and Beeler, was that non-Indigenous place name interpretations “depended to a large extent upon local [non-Indigenous] tradition and folklore for their explanations of a name’s meanings,” resulting in “numerous highly conjectural and often fanciful etymologies, many of which have been copied over and over again in succeeding publications” (1996, 188). Thus, the interpretation of place names in any new research project should largely come from those within the language, culture, and worldview, mitigating misinterpretation of possible meanings. In the same vein, in order to avoid inadvertently prescribing values from outside of the Kanyen’kehá:ka homeland, Ingram’s dissertation used grounded theory to analyse the data for patterns in meaning or patterns in the use of a particular aspect of landscape, culture, history, etc. The analysis determined that Kanyen’kéha place names focus heavily on water, even when elements of a name appear to be associated with land (such as the English interpretation of meadow or island), lending weight to the importance of ethnophysiographic elements as well as to the importance of working directly with those holding an understanding of the language, landscape, and culture (Ingram 2020).

Although the dissertation has been given to the communities and is available as an open-source document on the internet, it could be considered inaccessible to any non-academic or non-linguist given the technical language. Similarly, although the dissertation presents a number of images, including maps, it remains a static document that relies on writing rather than other forms of communication. Simply seeing and understanding the meaning of a name does not necessarily translate to knowing the landscape of that particular location or knowing how to practice the activities that occur at those locations. In other words, knowing that a name means “Hazelnut Island” does not equate to knowing what that place looks like or how to go about gathering hazelnuts at that location, only that it is an island and that there are hazeluts there. This is an example of the disconnect between language, landscape, and culture represented in the O’nonna model, and although the dissertation provides access to one element of the O’nonna model (language), it does not reconnect the elements of the triad. Additionally, Indigenous Knowledge is often transmitted in multiple, interwoven forms not exclusive to language, such as songs, imagery, or physical demonstrations of skills, none of which can be effectively represented on paper. Without the ability to reproduce these differing modes of communication, some parts of the message are likely to be lost in transmission. However, new forms of technology, particularly those related to digital mapping, aid in making this knowledge more accessible.

Digital Mapping

Until the internet revolution of the late 1990s, the modern-day map, derived from a traditional European conceptualization of a model of space (Harley 1989), remained relatively static: whether as a single sheet in an atlas collection, as a globe, or on a computer screen, these representations largely remained lines, curves, and polygons, and the written form of a place name with additional information was presented separately and statically (e.g., textual descriptions or photographs of a location accompanying a map). Given that Indigenous Knowledge of landscape is complex and interwoven through numerous cultural devices such as oral histories, stories, songs, dances, or other mnemonic devices such as wampum (UNESCO 2017), and that often places are marked for a specific action or activity that occurs at a place (Ingram 2020), static maps may not be able to preserve the original form in which the spatial message is transmitted. For example, a song that mentions a place and the significance of that place may be written down on paper in both musical notation and as lyrics. However, some aspects of that knowledge will inevitably be lost since the transmission is not the original mode of communication (i.e., a song cannot be “sung” nor “heard” on paper). The static nature of paper forces multimodal aspects of spatial transmission, such as the pronunciation of the place name, a panoramic photo of the place, or the ability to watch an activity derived from the importance of that place, to be compartmentalized into individual modal aspects, which can then be interpreted on paper. On paper, Indigenous Knowledge, normally interwoven through various social and physical aspects, is siloed. As a result, the language, culture, and landscape entwined in the components and expressions of place naming are also kept distinct from each other.

In addition, traditional mapmaking practices have been used as colonial tools. Critical cartography provides a response to a lack of representation of Indigenous Knowledge, epistemology, and ontology in the production of models of space in traditional maps, as well as to the ongoing dispossession of Indigenous lands and resources enabled by the creation of such maps. Harley’s “Maps, Knowledge, and Power” (1988, reprinted in 2008) and “Deconstructing the Map” (1989) outline how maps have essentially been used as a tool of imperialism not only because of their use for dispossession of land through ideas of terra nullius, but also because they are rooted in non-Indigenous practices, methodologies, and worldviews. According to Wood et al., critical cartography arose as a formal subfield of cartography in “the late 1980s and early 1990s in opposition to the hegemonic description of mapmaking as a progressive and value-free transcription of the environment” (2010, 120). In response, Indigenous Peoples have appropriated the very tools and technologies that have historically led to the loss of their lands, territories, and resources due to centuries of colonization and have integrated methods that focus on collaboratively built knowledge by incorporating Indigenous ways of knowing and being, epistemologies, ontologies, and methodologies (Hirt 2022).

Digital mapping, particularly participatory digital mapping, aligns with a critical cartographical approach by enabling the incorporation of Indigenous Knowledge and worldviews in the recording of place-based knowledge. Participatory mapping practices are a complement to critical cartography because they involve “accessing, integrating, and elevating local ‘voices’ (i.e., perspectives, values, knowledge, data)” through community members sharing Indigenous Knowledge, “describing their relationship to their landscapes and resources – their lived experience” (Laituri et al. 2023, 2), and digital maps have proven to be “valuable, adaptable, and effective tools in supporting community priorities including language revitalization, use of syllabics, land-based learning, connecting with the ancestral land, and land-use planning” (Wojtuszewska 2019, i). Digital platforms offered by ESRI, Mapbox, Google, and others7 now offer the ability for users to map their own spaces using their own language and knowledge.

Furthermore, most contemporary digital mapping platforms use a database to organize data, which can then be visualized in different views on a map. In many mapping platforms, multimedia can be coupled with a location, providing several different types of visuals as well as audio and visual capabilities where possible; this may also help to accommodate knowledge that is passed in different forms such as song, dance, artwork, etc. Multimedia mapping represents an important aspect of both participatory mapping and critical cartography in that

Giving voice to Indigenous knowledge holders, makes it possible, on the one hand, to minimize the decontextualization of knowledge caused by the shift from oral to written forms, and, on the other hand, makes it possible to promote the direct expression, and therefore the most accurate possible, of Indigenous worldviews and territorialities, thanks to the absence of an intermediary or translator. (Hirt 2022, 178)

The next section provides an overview of the methodology for the atlas project, including the decision to use the Nunaliit Cybercartographic Atlas Framework platform and the participatory mapping approach we use to identify and document place names.

The Atlas of Kanyen’kehá:ka Space

In order to make the place names compiled within the dissertation easier to access in a manner based more on visualization rather than academic language, the Atlas of Kanyen’kehá:ka Space Research Project was formed. Having previously worked with the Geomatics and Cartographic Research Centre (GCRC) at Carleton University, Ingram and Horn-Miller elected to use the GCRC’s digital mapping platform, the Nunaliit Atlas Framework, to document Kanyen’kéha place names in the Atlas of Kanyen’kehá:ka Space. In addition to making the materials accessible at a single online location, the mapping framework used for the project enables communities to add their own information in various forms: they can mark locations that they deem important, enter data regarding these places, and add multimedia information complementing those locations.

The Atlas of Kanyen’kehá:ka Space project comprises both Kanyen’kehá:ka and non-Indigenous collaborators. The primary investigators are Kahente Horn-Miller, Kanyen’kehá:ka, and Fraser Taylor, director of the GCRC. Ingram, formerly supervised by Horn-Miller as a PhD student, acts as the liaison between the GCRC and Kanyen’kehá:ka communities and is the primary lead at community mapping workshops. Lily Ieroniawákon Deer of Kahnawà:ke, at the time a master’s student at Concordia University, served as research assistant during the first years of the project. Members of the communities of Akwesasne, Kehntè:ke, and Kahnawà:ke are also an integral part of the mapping team and help to determine direction and future avenues of the project. During the first year, a group of interested Kanyen’kehá:ka community members formed a Kanyen’keha:ka Mapping Collective to help guide the project. Key members include Thohahènte of Kehntè:ke, Ryan Nihawenná:’a Ransom of Akwesasne, and Kahentinetha Horn of Kahnwà:ke. In spring of 2023, the Akwesasne Cultural Center Library and Museum partnered with the atlas project.

Nunaliit uses a document-oriented database to store data attributes and objects, which allows for the display of media attachments such as photos; other images such as maps, documents, and drawings; PDFs; videos; audio files such as pronunciations of place names; and text for notes and community stories. The framework is open source, and its documentation and code are stored in a GitHub repository, where new code and documentation are updated as various atlas projects continue to evolve. Currently over twenty atlases have been made using Nunaliit; links to these atlases can be found on the GCRC atlas website. At present, the Atlas of Kanyen’kehá:ka Space utilizes photos; historical and treaty texts; audio files of pronunciations; video of explanations of landscape phenomena and place names; and drone footage. Atlas users, either with the help of GCRC staff or on their own, can create their own data attributes and provide any sort of attachment (audio and video files, text, photos, drawings and other images, scanned documents, PDFs, ZIP files, etc.) to create the multimedia atlas experience. When users add a point to an atlas, they can record audio and video directly within the digital platform through the web browser, and these files will automatically be associated with that specific point. This is significant since the associated media can be recorded directly within the community, so there is no need for community members to leave their homes in order to share their knowledge. Thus, control of which points to mark, their location, and the media elements associated with those points lies entirely with the community undertaking the mapping. The association of media to a specific point can also be used for language-learning purposes in that those learning the language then have access to a recording of the proper pronunciation of a word or name; an explanation of the grammatical components of a word, phrase, or name; or even recordings or texts of entire stories or discussions in the language itself. These multimedia capabilities represent one way in which technology—in this case, the Nunaliit Atlas Framework—may aid in the reconnection of the three elements of the O’nonna model by associating the language available through the media files with the landscape, which not only takes the form of a pin on the atlas but can also be represented through photos, videos, map scans, etc.

Community-based participatory mapping8 is a key element of the cybercartographic method (Taylor 2005; Ingram et al. 2019) upon which Nunallit was based. This is an iterative process beginning with initial discussion of the overall purpose of an atlas project, the programming of a “first draft” atlas for that purpose, and the initial population of the atlas by the community. As patterns emerge in relationships within the data, users create “schemas,” which help to organize and display objects in the database thematically. This essentially creates the “next draft” of an atlas, into which more information can be added and organized by a theme under the created schemas. Schemas and general functionality of the atlas can be modified to accommodate the addition of new schemas (themes), data attributes, or attachment types as needed (Geomatics and Cartographic Research Centre 2018). This cycle of organization, data addition, analysis, and reorganization can be repeated as many times as the community sees fit. The information outlined in this article represents the work leading to and creation of the “first draft” of the Atlas of Kanyen’kehá:ka Space. After discussion with community members and Carleton team members, two base maps were chosen for the first iteration of the atlas. The Sentinel 2 Cloudless mosaic satellite imagery was chosen since it is open source and not subject to the same changes or restrictions as, for example, NOAA or Google satellite imagery, and it is suitable for pre-colonial mapping purposes since it displays no labels and no areal, political, or administrative boundaries. A second base map, Open Street Maps, was also added in order to provide users with an orientation layer as necessary. The atlas was then partially populated by Ingram using historical information, both for testing purposes and as a demonstration of the functionalities of the atlas for planned community mapping workshops.

Mapping Workshops

Mapping workshops were scheduled to help familiarize communities with the atlas and begin to populate it with community-driven place name data. Two specific methods were devised for these workshops. To help focus discussion on place names, we began workshops with a discussion of the participants’ knowledge of Kanyen’kéha place names and their knowledge of places both within the community and the wider Kanyen’kehá:ka homeland. The workshop coordinators asked community members about place names in use in the community, including neighbourhood and street names, and names for physical features in the area, such as rivers. Examples include neighbourhoods such as Otskwa’rhéhne (“at the home of the frogs”/“Frogtown”), Kataró:kon (“under the clay”/“Clay Hill”), and a section of the St. Lawrence River at Akwesasne known as Ahnawà:te (“the Rapids”).

Because much of Kanyen’kehá:ka knowledge of place is still held within the oral tradition, we prioritized Kanyen’kehá:ka oral history of place as the source of place names for the atlas. However, we also used non-Indigenous-authored paper maps and other archival documents that have preserved Indigenous place names. Although requiring several types of linguistic analysis (see Ingram 2020), archival sources potentially hold place names and related information that may help to spur discussion related to meaning, grammar, descriptive lexical elements, and the landscape itself. Thus, a second method utilized during workshops was the introduction of place names taken from these archival sources or the introduction of the archival sources themselves in the form of copies of digitized maps printed using a large-scale map printer. This method proved particularly fruitful in Akwesasne, as related below.

COVID-19

Although this project was always envisioned as a community-driven effort, the realities of COVID-19 forced us to revise elements of the project in order to protect the research team, community members, and our families. Our inaugural workshop was scheduled for March 2020, and the provinces of Ontario and Quebec entered lockdown several days before it was supposed to take place. As it became clear that the lockdowns would continue long term, the assistant director of the GCRC, Peter Pulsifer, made us aware of a strategy used by the Exchange for Local Observations and Knowledge of the Arctic (ELOKA), based at the University of Colorado Boulder, to assist in training in the use of Nunaliit atlases in remote areas. This approach consisted of training videos posted to the internet that outlined the steps in understanding and using basic atlas functions such as pan, zoom, switching between layers, and account creation. Using ELOKA’s training video as a template, Ingram and Deer transcribed the video to create a script, separated the script into smaller elements, and edited the script to be relevant to the tools and functions of the Atlas of Kanyen’kehá:ka Space. Using various types of audio- and screen-capture software as well as PowerPoint, we recorded the video remotely through our individual computers. We then made the videos available on Vimeo as short feature-specific segments as well as one longer compilation video containing training on all of the feature-specific segments. We scheduled introductory Zoom sessions for Akwesasne, Kahnawà:ke, and Kehntè:ke (Tyendinaga) in which we used the video to demonstrate the atlas as well as provided more detailed explanations and answered questions when necessary. Finally, in July 2021, we were able to hold in-person mapping workshops. We began in Akwesasne, followed by Kehntè:ke and Kahnawà:ke. Each workshop was held over the course of two days, generally a Friday and a Saturday. Highlights for each mapping workshop are detailed below.

Workshop in Akwesasne

The Kanyen’kehá:ka community of Akwesasne is “uniquely situated in two countries, two provinces and one state” (White 2015) and straddles the border between what is today called the United States (New York state) and Canada (the provinces of Ontario and Quebec). This workshop was hosted by the Native North American Traveling College (NNATC). Because of COVID, we maintained a low capacity and had around eight people attend over the course of the two days. One participant who was also an employee of the college, Karonhianonha Francis, had discovered a paper map from a 1997 geographic information system (GIS) workshop at NNATC that had many Kanyen’kéha names, especially for many of the islands found in the St. Lawrence River around which the community of Akwesasne is centred. We collectively decided to add all of the names on the paper map to the atlas along with recordings of the pronunciations in Kanyen’kéha and other information and media. Two main themes emerged during this process that revolved around the use of the language. The first was the meanings of the names and the second was the reasons for the naming. The meanings of some names, such as Otskwa’rhéhne (called “Frogtown” in English, meaning literally “the home of the frogs”), were obvious to community members, while others were less clear. Sometimes this lack of clarity was due to the grammatical structure of the language. In that case, we undertook morphological analysis for several of the names in order to try to better understand the meaning and the grammatical construction.

The mapping workshop created the space to have conversations about grammar and meaning specifically as these relate to landscape and place. Kanyen’kéha is structurally a polysynthetic language, making it markedly different from Indo-European languages such as English or French. As a result, the concepts of “nouns” and “verbs” appear more like “noun phrases” and “verb phrases” than in Indo-European languages, which is applicable to place names. Phrases consist of a root that carries the central meaning. Various prefixes and suffixes must be attached to this root in order to form a grammatical phrase (Mithun 1996). These prefixes and suffixes also often encode other grammatical concepts (Mithun 1984; Chafe 2012; Baker 1996) like whether the phrase describes a state of being (statives), whether the described is located in a direction towards or away from the speaker (spatial deixis), and whether the described is likely to “designate things found in nature” or “designate manmade objects” (Ontario Ministry of Education 2011, 11). These grammatical elements were all discussed during the workshop as part of the grammatical analysis of the place names. Ultimately, these conversations spilled outside of the workshop space itself and into the community, with one of the participants calling a first-language speaker via FaceTime to ask if we were interpreting a name and the name construction correctly.

Other place names, such as an island called Kitkithne (“Hen Island”), were semantically and grammatically understandable, but were still pragmatically curious in that we did not understand the reason that name was given. Kitkithne is essentially a large rock in the river; it is not a particularly hospitable place and could not be inhabited without outside resources. It was possibly used as a fishing spot or navigational marker, but in either case it would only have been accessible by boat. It is likely that, as people at Akwesasne relied more on cars for navigation and relied less on locally caught fish, the place name became less used in general (both in Kanyen’kéha and in English). As noted earlier, it is not necessary to understand the meaning of a place name in order to utilize a place name, which is why place names are borrowed from one language into another and, as Waterman (1922) points out, persist even when a language ceases to be spoken (Ingram 2020). This also accounts for why the meanings of place names may be forgotten, even if they were known in the first place. The fact that a name serves as a cognitive representation not necessarily related to its meaning is the reason that many place names, or elements of place names, are borrowed from other languages and why we find names such as Syracuse, Rome, and Ithaca in the middle of New York state or Paris in southwestern Ontario, far from their origins. This is also why so many Indigenous names continue to be used in North America when their original meanings, or even their naming language, is no longer recognized (Ingram 2020). Thus, it may be that the meanings of the names for the islands are not known in either English or Kanyen’kéha simply due to lack of use. In this case, the mapping workshops provided the space to discuss place names that had been located in various sources through archival research, and to talk about community understanding and historical knowledge of those locations as well as land use, occupancy, and environmental factors. Together with an awareness of the need for language use as part of overall language stabilization and revitalization, mapping workshops also allow for the community to decide if they wish to reclaim and reinvigorate historical place names by interpreting the names and then reintroducing the use of the names back into the community by mapping them in the atlas. Interestingly, in one case, the community went even further by translating a name that appeared only in English, Goose Island, into Kanyen’kéha as Kahónkhne (“home of the goose”) during the workshop, and this name was entered into the atlas to be used as the preferred name for that location.

Many of the participants added their own media files to the points on the atlas. These included photos of the local arena, the international bridge between the United States and Canada, the NNATC campus, and photos of landscape features such as many of the aforementioned islands, which are visible from land. However, also pinned were video recordings of the actual linguistic analysis of the place names in which several participants broke down the structure of the name into prefixes, roots, and suffixes on a dry-erase board. With the ability to pin the recorded discussion of grammatical construction and analysis of a place name to the name itself on the digital atlas, the Atlas of Kanyen’kehá:ka Space enables not only the documentation and conservation of the names themselves, but also the grammatical structure of those names. It also digitally connects the landscape (the model displayed on the atlas and the photos and videos of the landscape as pinned to the model), the language (the place name written on the pinned place, the audio pronunciations pinned to a place, and the video recordings of the morphological work), and the culture (attestations of what is done at a place, or the reason for place naming). With the Atlas of Kanyen’kehá:ka Space, we are able to dynamically document all aspects of the O’nonna model instead of documenting only a single aspect of landscape, language, or culture.

During this workshop, approximately forty place names and over twenty media files were entered into the atlas. In 2023, the atlas team entered into a partnership with the Akwesasne Cultural Center Library and Museum, which now houses a large touchscreen display of the atlas for the use of the community as well as visitors.

Workshop in Kehnté:ke (Tyendinega)

Kehntè:ke, known in English as Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory, is located approximately forty miles west of Kingston, Ontario, on the northern shore of Lake Ontario. During the American Revolutionary War, in which the Kanyen’kehá:ka were allied with the British Crown, many Kanyen’kehá:ka were forced from their homeland in present-day New York state. Following the conclusion of the war, “in recompense for the loss of the homelands and in recognition for their faithful military allegiance with the British Crown, the Six Nations were to select any of the unsettled lands in Upper Canada” (Tsi Tyónnheht Onkwawén:na and the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte Research Department 2022, n.p.). As part of the Simcoe Deed, otherwise known as Treaty 3 ½, 92,700 acres of land were deeded to the Six Nations in 1793 at the site of present-day Tyendinaga (Tsi Tyónnheht Onkwawén:na and the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte Research Department 2022, n.p.). Around twenty families travelled to the tract in 1784, and the date of their arrival, May 22, is marked every year with a re-enactment and ceremony (Tsi Tyónnheht Onkwawén:na and the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte Research Department 2022, n.p.). Following their arrival, the government of Canada began to give away the land deeded to the Kanyen’kehá:ka to United Empire Loyalists relocating from the United States. As a result, “within a span of 23 years (1820-1843) two-thirds of the treaty land base under the Simcoe Deed was lost,” leaving around 18,000 acres in the present day (Tsi Tyónnheht Onkwawén:na and the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte Research Department 2022, n.p.). Oral history states that Kehntè:ke was originally a Wendat village and the home of the Peacemaker who successfully allied all five of the Haudenosaunee Nations together to create the Iroquois Confederacy (Tsi Tyónnheht Onkwawén:na and the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte Research Department 2022, n.p.). Following the so-called Beaver Wars of the late 1600s, some Wendat, whose language is related to Kanyen’kéha, joined the Kanyen’kehá:ka in the St. Lawrence and Mohawk River valleys, bringing with them their landscape and environmental knowledge of the area (Parmenter 2010). Thus, “these lands were not unknown to the Six Nations people as they were part of a vast northern territory controlled by Iroquois Confederacy prior to the Royal Proclamation of 1763” (Tsi Tyónnheht Onkwawén:na and the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte Research Department 2022, n.p.).

The Kehntè:ke workshop was held at the Kanhiote Library with seven participants. Given that the use of an archival map had been successful in Akwesasne, we decided to present workshop participants with place names from a map created by Wallace Havelock Robb and published in his book Thunderbird in 1949. This method again proved fruitful as one participant, for whom Kanyen’kéha was their first language, was able to identify a place name, Sagonaska, that was grammatically correct and entirely understandable to her but that she had never heard before. As this name represented a description of a waterway, specifically where a large body of water joins with a smaller body of water, it essentially expanded her knowledge of the landscape domain in Kanyen’kéha. The same map prompted a discussion on an island named simply Ojistoh (“star” in Kanyen’kéha), which is located at one “corner” of the Z-shaped Bay of Quinte. Listed as a point of navigation by Robb, participants realized that this was a reference to navigating by use of the North Star and that this island would have been used for guidance in the correct direction towards the original village, as the unique shape of the bay can quickly become maze-like. The instinct of at least one English speaker was that the name was related to a physical description of the island or had something to do with a literal star, which reinforces the importance of interpreting place name meanings from within the culture rather than from outside the naming group. To avoid misinterpreting names through the imposition of external cultural and ethnophysiographical perceptions, place name studies should be undertaken in conjunction with members of the naming group.

During the course of this workshop, there was discussion that many of the important sites on the map were not located on the reserve itself, but rather in Prince Edward County, located just south of the community, formerly a peninsula that became an island with the construction of the Murray Canal (Parks Canada 2022). A small subgroup of the workshop participants decided that we would drive to Lake on the Mountain Provincial Park and that the participants would narrate some of the culturally important landscape features as we drove. This is a method discussed by Nash and Simpson (2012), although using newer technology (our cell phones and other recording equipment). The Nunaliit platform allowed us to drop these recordings into the atlas almost instantaneously from the location itself. For many locations, the multimedia represent what could be considered “raw data,” which may remain as is in the atlas or may be edited in the future according to the community’s wishes.

Workshop in Kahnawà:ke

The community of Kahnawà:ke is located on the St. Lawrence River directly south of the city of Montréal. The St. Lawrence itself has a long history of Iroquoian presence, having been inhabited by the “Laurentian Iroquois” at the time of Jacques Cartier’s 1534, 1535, and 1542 voyages to Canada, during which he travelled as far as the Gaspé Peninsula (Fischer 2008). The island of Montréal was the site of the Laurentian town of Hochelega, documented by Cartier and later visited by Samuel de Champlain (Fischer 2008). The Laurentian Iroquoian also occupied a site across the river from Hochelaga known as Kentaké, and, following the establishment of the colony of Montréal, this became a location of heavy trade from which the community of Kahnawà:ke was eventually established in the latter half of the seventeenth century (Parmenter 2010). Although the exact location of the town has shifted twice, it is still located within ten miles of its original establishment (Ingram 2020). Thus, the knowledge of and experience with the landscape in this community spans centuries.

This workshop was held at the Golden Age Club in Kahnawà:ke, located directly on the St. Lawrence Seaway, with three participants. Because a number of people working on the atlas were from the area, some local place names, such as Kataró:kon (“under the clay”), had already been added. Therefore, we began by exploring some of the names documented by Cartier and reproduced in Robinson’s “Some of Cartier’s Place-Names 1535–1536” (1945). Although these are either Wendat or Laurentian Iroquoian, several of these names appeared to be easily understandable despite their age. One name, represented as Deganonda and Thegnignonda (as well as possibly Thequenondahy), could be straightforwardly read as Tekanonta, which was translated as “two hills” or “double hill.”9 For this task, we wrote each name as it was represented by Robinson/Cartier on a chalkboard followed by an approximation in Kanyen’kéha, a technique that Ingram developed in her dissertation. We then analyzed the individual linguistic elements of each name, discussed possible meanings, and decided if a name and its meaning should be added to the atlas. A picture of the blackboard with the linguistic analysis of each element was added to the point representing the place name.

Perhaps because of the proximity of the workshop location to the St. Lawrence Seaway, another recurring topic during the workshop was the effect of the modification of this waterway on the community of Kahnawà:ke. As outlined by Deer (2017), the Seaway had a major impact on the community within living memory. Several people discussed locations of importance to them that had been destroyed during the construction of the Seaway, including family homes and farms. Since this topic was particularly emotional, it was decided that we would visit some of the locations but hold off on adding them to the atlas until such time as we could determine how to deal with such sensitive content. This will be discussed in future iterations of the atlas.

Summary and Next Steps

Two main methods have proven useful in the documentation of Kanyen’kéha place names for the Atlas of Kanyen’kehá:ka Space. We have proven that many historical Kanyen’kéha names are still interpretable to Kanyen’kéha speakers despite, in some cases, centuries of time having passed since their documentation. This means that the ethnophysiographical, historical, environmental, cultural, and other information contained within them is still recoverable, even if the place name has fallen out of general use. This information can potentially be retrieved and reintegrated into the Kanyen’kehá:ka knowledge complex through the methodology outlined in this paper and the use of the Atlas of Kanyen’kehá:ka Space. This is extremely significant given that the Kanyen’kehá:ka were removed from their homelands along the Mohawk River in New York state and relocated to an area at the extreme north of their territories because the information contained within the historical place names may help to revive perceptions and associated cultural practices from those original territories. For example, a winter camp and an ancient corn field have both been located as a result of the place name work. This process has also reinvigorated older place names into use in the modern day, with some speakers deciding to use the older place names in place of newer ones going forward. The use of Kanyen’kéha place names instead of non-Indigenous place names represents a small reverse in language shift. Equally as important, it represents the potential reclamation of landscape knowledge that was formerly lost or unrecognized. This act of recognition and reclamation of place names represents language and landscape, both aspects of O’nonna. In the case of both the corn field and the winter camp, it is also clear which cultural activities took place at those locations. Thus, all three aspects of O’nonna are again present for those names and have only to be reconnected.

There are also many contemporary local place names in use in the three Kanyen’kehá:ka communities mentioned in this paper, and while some of these are American English, Canadian English, or Canadian French place names, others are Kanyen’kehá:ka place names. The addition of the contemporary names into the atlas serves as language documentation of land-based knowledge. The addition of further complementary information in the form of multimedia and text aids in representing the full breadth of Indigenous Knowledge associated with these places. Further linguistic information, such as the meaning and pronunciation of the name and explanations of the language used, can aid in ensuring that community members fully understand the significance of the name and can use the name and associated language as part of revitalizing the Kanyen’kéha language. Fettes outlines how this reinvigoration may represent “a small step towards language renewal” (1997, 309). Perhaps even more importantly, place name reinvigoration also represents a “way to honour places and our relationship with them” because “to speak old names is to begin to learn an original way of seeing the world around us” (Tsunoda 2006, 221). Thus, the act of mapping, documenting, and preserving place names of a group’s traditional territory is significant for linguistic, environmental, and cultural reasons. Once all three of these elements exist for a location, the work to reconnect these elements can begin.

In terms of next steps, the Atlas of Kanyen’kehá:ka Space partnered with the NNATC in 2022 as part of a grant from the National Indian Brotherhood to plan and run a summer camp exploring the use of the atlas to facilitate interaction between language speakers and language learners as part of the Mentor-Apprentice method of language learning and revitalization. The initial camp took place in July 2022 and was followed by a second camp in August 2023 at the Akwesasne Cultural Center Library and Museum, funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. The third annual summer camp took place in July 2024. We hope that this work will provide a methodology for reconnecting the three elements of O’nonna through online participatory mapping. An overview of this methodology and the language curriculum is outlined in Ingram, Horn-Miller, and Ransom (forthcoming).

This article has demonstrated the importance of Indigenous place names, with a focus on the Kanyen’kehá:ka in particular. Names given to locations by Indigenous people that are based on interactions with an environment over millennia retain important environmental, cultural, historical, and ethnophysiographical information, which is passed intergenerationally through these descriptive linguistic terms. The O’nonna model demonstrates how place names are a form of language that links landscape and culture. However, these connections are disrupted, and potentially eliminated, when any single element of O’nonna is disrupted, whether through the dispossession of land, suppression of cultural activity, or pressure of colonial languages causing language shift. The consequent attrition of language, especially in the domain of landscape and ethnophysiographical terms, may cause the original meanings and connections represented by place names to be lost completely.

We have also shown, through the Atlas of Kanyen’kehá:ka Space project, that place names and their meanings, as well as the knowledge of the landscape they carry, are recoverable. The process of creating a digital atlas, supported through work with Kanyen’kéha speakers and community members, linguistic theory, and archival documentation, reinvigorates the individual elements of O’nonna and helps restore the interrelationship between them. Through a series of workshops and camps based in Akwesasne, Kehntè:ke (Tyendinaga), and Kahnawà:ke, the project has successfully engaged community members in using the atlas as a facilitator to document Kanyen’kéha place names, their meanings, their locations, related landscape-based information, and the cultural practices relevant to that location through text, visualizations, and multimedia materials. This can then further expand the landscape domain and the cultural domains of language, to act as a tool to help hold language attrition at bay, to serve as a starting point for revitalization activities, and to aid in the reclamation of Kanyen’kehá:ka conceptions of space.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the two anonymous reviewers and to the editor for their valuable comments and editorial suggestions.

Ethics

Ethics approval was obtained from Carleton University Research Ethics Board A under protocol #111948.

References

Afable, Patricia, and Madison Beeler. 1996. “Place Names.” In Handbook of North American Indians, 17, edited by Ives Goddard. Smithsonian Institution.

Baker, Mark C. 1996. The Polysynthesis Parameter. Oxford University Press.

Berleth, Richard. 2009. Bloody Mohawk: The French and Indian War and American Revolution on New York’s Frontier. Black Dome Press.

Chafe, Wallace. 2012. “Are Adjectives Universal? The Case of Northern Iroquoian.” Linguistic Typology 16 (1): 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1515/lity-2012-0001.

Cogos, Sarah, Marie Roué, and Samuel Roturier. 2017. “Sami Place Names and Maps: Transmitting Knowledge of a Cultural Landscape in Contemporary Contexts.” Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research 49 (1): 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1657/AAAR0016-042.

Davidson, Sara Florence, and Robert Davidson. 2018. Potlatch as Pedagogy: Learning Through Ceremony. Portage & Main Press.

Deer, Lily Ieroniawakon. 2017. “‘Plus Ten Percent for Forcible Taking’: Construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway as Environmental Racism on Kahnawà:ke.” HPS: The Journal of History and Political Science 5: 13–25.

Farrell, Justin, Paul Berne Burow, Kathryn McConnell, Jude Bayham, Kyle Whyte, and Gal Koss. 2021. “Effects of Land Dispossession and Forced Migration on Indigenous Peoples in North America.” Science 374 (6567). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abe4943.

Fettes, Mark Thompson. 1997. “Stabilizing What? An Ecological Approach to Language Renewal.” In Teaching Indigenous Languages, edited by Jon Allan Reyhner. Northern Arizona University.

Fischer, David Hackett. 2008. Champlain’s Dream. Simon & Schuster.

Geomatics and Cartographic Research Centre, Carleton University. 2018. “Nunaliit Atlas Framework.” http://nunaliit.org/. Archived at: https://perma.cc/99UT-U62E.

Harley, J. B. 1989. “Deconstructing the Map.” Cartographica: The International Journal for Geographic Information and Geovisualization 26 (2): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3138/E635-7827-1757-9T53.

Harley, J. Brian. (1988) 2008. “Maps, Knowledge, and Power.” In Geographic Thought: A Praxis Perspective, edited by George Henderson and Marvin Waterstone. Routledge.

Harris, Leila M., and Helen D. Hazen. 2015. “Power of Maps: (Counter) Mapping for Conservation.” ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 4 (1): 99–130. https://acme-journal.org/index.php/acme/article/view/730. Archived at: https://perma.cc/5PL2-GWTR.

Helleland, Botolv. 2012. “Place Names and Identities.” Oslo Studies in Language 4 (2): 95–116. https://doi.org/10.5617/osla.313.

Hercus, Luise, Jane Simpson, and Flavia Hodges, eds. 2009. The Land Is a Map: Placenames of Indigenous Origin in Australia. ANU Press. https://doi.org/10.26530/OAPEN_459353.

Hill, Susan M. 2017. The Clay We Are Made of: Haudenosaunee Land Tenure on the Grand River. University of Manitoba Press.

Hinge, Gail, under contract to Department of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. 1985. “An Act Further to Amend ‘The Indian Act, 1880.’ S.C. 1884, c. 27.” In Indian Acts and Amendments 1868–1975, vol. 2 of Consolidation of Indian Legislation. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2017/aanc-inac/R5-158-2-1978-eng.pdf.

Hirt, Irène. 2022. “Indigenous Mapping: Reclaiming Territories, Decolonizing Knowledge.” In The Politics of Mapping, edited by Bernard Debarbieux and Irène Hirt. Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119986751.ch7.

Ingram, Rebekah, Erik Anonby, and D. R. Fraser Taylor. 2019. “Mapping Kanyen’kéha (Mohawk) Ethnophysiographical Knowledge.” In Further Developments in the Theory and Practice of Cybercartography: International Dimensions and Language Mapping, edited by D. R. Fraser.

Ingram, Rebekah. 2018. “Mapping Indigenous Landscape Perceptions.” Paper presented at the FEL XXII (2018) Endangered Languages and the Land: Mapping Landscapes of Multilingualism conference, Reykjavik, Iceland, April 23–25, 2018.

Ingram, Rebekah. 2020. “Naming Place in Kanyen’kéha: A Study Using the O’nonna Three-Sided Model.” PhD diss., Carleton University. https://doi.org/10.22215/etd/2020-13999.

Ingram, Rebekah, Kahente Horn-Miller, and Ryan Ransom. Forthcoming. “O’nónna: A Curriculum for Land-Based Language Learning.” Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics.

The Institute for Name-Studies. 2019. Key to English Place-Names. University of Nottingham. http://kepn.nottingham.ac.uk/#.

Jett, Stephen C. 2001. Navajo Placenames and Trails of the Canyon de Chelly System, Arizona. Peter Lang.

Jobin, Shalene. 2016. “Double Consciousness and Nehiyawak (Cree) Perspectives: Reclaiming Indigenous Women’s Knowledge.” In Living on the Land: Indigenous Women’s Understanding of Place, edited by Nathalie Kermoal and Isabel Altamirano-Jiménez. AU Press.

Jordan, Peter. 2012. “Place Names as Ingredients of Space-Related Identity.” Oslo Studies in Language 4 (2): 117–31. https://doi.org/10.5617/osla.314.

Julian, Charles. 2010. “A History of the Iroquoian Languages.” PhD diss., University of Manitoba. http://hdl.handle.net/1993/4175.

Laituri, Melinda, Matthew W. Luizza, Jamie D. Hoover, and Arren Mendezona Allegretti. 2023. “Questioning the Practice of Participation: Critical Reflections on Participatory Mapping as a Research Tool.” Applied Geography 152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2023.102900.

Mark, David M., Andrew G. Turk, and David Stea. 2010. “Ethnophysiography of Arid Lands: Categories for Landscape Features.” In Landscape Ethnoecology: Concepts of Biotic and Physical Space, edited by Leslie M. Johnson and Eugene S. Hunn. Berghahn Books.

Meyer, Julien. 2021. “Environmental and Linguistic Typology of Whistled Languages.” Annual Review of Linguistics 7 (1): 493–510. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-linguistics-011619-030444.

Mithun, Marianne. 1984. “The Evolution of Noun Incorporation.” Language 60 (4): 847–94. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.1984.0038.

Mithun, Marianne. 1996. “The Mohawk Language.” In Quebec’s Aboriginal Languages: History, Planning, and Development, edited by Jacques Maurais.

Mohawk Council of Kahnawà:ke. 2014. “Kanien’kéha Language Survey Results.” http://www.kahnawake.com/pr_text.asp?ID=2237. Archived at: https://perma.cc/3VU4-94DW.

Nash, David, and Jane Simpson. 2012. “Toponymy: Recording and Analysing Placenames in a Language Area.” In The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Fieldwork, edited by Nicholas Thieberger. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199571888.013.0018.

National Park Service. 2022. “The Clinton-Sullivan Campaign of 1779.” Fort Stanwix National Monument. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/the-clinton-sullivan-campaign-of-1779.htm. Archived at: https://perma.cc/2MHS-J6KT.

Ontario Ministry of Education. 2011. Native Languages: A Support Document for the Teaching of Language Patterns: Oneida, Cayuga and Mohawk. http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/curriculum/secondary/NativeLangs_OneidaCayugaMohawk.pdf.

Paradis, Michel. 2007. “L1 Attrition Features Predicted by a Neurolinguistic Theory of Bilingualism.” In Language Attrition: Theoretical Perspectives, edited by Barbara Köpke, Monika S. Schmid, Merel Keijzer, and Susan Dostert. Studies in Bilingualism, vol. 33. John Benjamins.

Parks Canada. 2022. “Murray Canal. Trent-Severn Waterway National Historic Site.” Last modified November 17, 2022. https://www.pc.gc.ca/en/lhn-nhs/on/trentsevern/visit/canal-murray. Archived at: https://perma.cc/X98V-57VX.

Parmenter, Jon. 2010. The Edge of the Woods: Iroquoia, 1534–1701. Michigan State University Press.

Randall, Richard R. 2001. Place Names: How They Define the World–and More. The Scarecrow Press.

Robb, Wallace Havelock. 1949. Thunderbird. Abbey Dawn Press.

Robinson, Percy J. 1945. “Some of Cartier’s Place-Names 1535–1536.” The Canadian Historical Review 26 (4): 401–5. muse.jhu.edu/article/624294.

Statistics Canada. 2017. “Census in Brief: The Aboriginal Languages of First Nations People, Métis and Inuit.” Government of Canada. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/98-200-x/2016022/98-200-x2016022-eng.cfm. Archived at: https://perma.cc/6W8L-JPMD.

Stewart, George R. 1975. Names on the Globe. Oxford University Press.

Taylor, D. R. Fraser. 2005. “The Theory and Practice of Cybercartography: An Introduction.” In The Theory and Practice of Cybercartography, edited by D. R. Fraser Taylor. Modern Cartography Series, vol. 4. Elsevier.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2015. The Survivors Speak: A Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. https://ehprnh2mwo3.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Survivors_Speak_English_Web.pdf. Archived at: https://perma.cc/9ZUF-FS9F.

Tsi Tyónnheht Onkwawén:na and the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte Research Department. 2022. “Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory.” In The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Article published February 15, 2022; last edited February 15, 2022. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/tyendinaga-mohawk-territory. Archived at: https://perma.cc/UE8U-V3TT.

Tsunoda, Tasaku. 2006. Language Endangerment and Language Revitalization: An Introduction. De Gruyter Mouton.

Turk, Andrew G., David M. Mark, Carolyn O’Meara, and David Stea. 2011. “Geography: Documenting Terms for Landscape Features.” In The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Fieldwork, edited by Nicholas Thieberger. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199571888.013.0017.

UNESCO. 2017. “What is Local and Indigenous Knowledge.” https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000259599.

University of Oxford. 2019. “History.” https://www.ox.ac.uk/about/organisation/history?wssl=1#. Archived at: https://perma.cc/7DP3-VAZ4.

Waterman, T. T. 1922. “The Geographical Names Used by the Indians of the Pacific Coast.” Geographical Review 12 (2): 175–94. https://doi.org/10.2307/208735.

White, Louellyn. 2015. Free to be Mohawk: Indigenous Education at the Akwesasne Freedom School. University of Oklahoma Press.

Wojtuszewska, Veronica. 2019. “On the Importance of Language: Reclaiming Indigenous Place Names at Wasagamack ᐘᕊᑲᒪᕁ First Nation, Manitoba, Canada.” Master’s thesis, University of Manitoba. http://hdl.handle.net/1993/33841.

Wood, Denis, John Fels, and John Krygier. 2010. Rethinking the Power of Maps. The Guilford Press.

Yom, Samantha JingYi, and Francesco Cavallaro. 2020. “Colonialism and Toponyms in Singapore.” Urban Science 4 (4): 64–74. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci4040064.

Footnotes

1 The Kanyen’kéha place names described throughout this paper can be accessed through the Atlas of Kanyen’kéha Space. Please note that although the Kanyen’kehá:ka communities mentioned here used the Eastern Mohawk variety spelling conventions, the authors use the Western Mohawk spelling conventions since this is the orthography in which they were originally trained.

2 For example, in his survey of the world’s whistled languages, Meyer outlines how these languages are tied directly to culture in that they are used for “specific traditional outdoor subsistence activities . in association with the coordination of group activities such as hunting, fishing, food gathering, hill agriculture/harvesting, or caring for cattle” (2021, 4). Meyer also describes how whistled languages are also connected directly to landscape, including mountainous areas, areas of dense vegetation, or both (2021, 6). The landscape inhabited by a certain group of people is reflected in and related to their culture, which is also reflected in and related to their language.

3 At one time, pow wows, Sundance, and potlatches were deemed illegal in Canada and the United States. Haida authors Davidson and Davidson describe potlatch as “the legal foundation of our social structure,” which “ensured the transmission of our cultural knowledge, as ‘among the Haida, all claims to social position must be witnessed and sanctioned by the public’” (2018, 5). An amendment to the Indian Act in 1884 made potlatching a misdemeanor punishable by imprisonment for a term of two to six months (Hinge 1985, 93). This law was revoked in 1951 (Davidson and Davidson 2018).

4 The residential school system remains one of the most direct causes of language loss. These schools actively discouraged or punished people for speaking their language (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2015). Jobin outlines how “students at residential schools were strictly forbidden to speak their native tongue and could be harshly punished for doing so. Instead, they were forced to speak only in English or, at some schools, in French” (2016, 44).

5 See, for example, Hercus et al. (2009), who link the erasure of Indigenous place names in Australia to the weakening and endangerment of the language of the namers.

6 For example, Oxford is literally “oxen ford” (The Institute for Name-Studies 2019), but very few people (if any) still make use of oxen for transportation or, for that matter, have any reason to ford the River Thames. Instead, this place is often associated with the University of Oxford, the “oldest university in the English-speaking world” (University of Oxford 2019). Thus, the name has become semantically bleached from its literal meaning (“oxen ford”) to a sense of place, i.e., “the place where the oldest university in the English-speaking world is located.” The original meaning, while still somewhat obvious, has become opaque, and the place name has become a cognitive representation of a geographic location. This is arguably what has occurred in North America when Indigenous place names were borrowed into English or French place-naming systems (Ingram 2020).

7 We advise users to evaluate the data privacy policies of any digital platform before using it to document their Traditional Knowledge.