RESEARCH ARTICLE

Ethical Considerations of Including Gender Information in Open Knowledge Platforms

Nerissa Lindsey

San Diego State University

Greta Kuriger Suiter

Ohio University

Kurt Hanselman

San Diego State University

In recent years, galleries, libraries, archives, and museums (GLAMs) have sought to leverage open knowledge platforms such as Wikidata to highlight or provide more visibility for traditionally marginalized groups and their work, collections, or contributions. Efforts like Art + Feminism, local edit-a-thons, and, more recently, GLAM institution-led projects have promoted open knowledge initiatives to a broader audience of participants. One such open knowledge project, the Program for Cooperative Cataloging (PCC) Wikidata Pilot, has brought together over seventy GLAM organizations to contribute linked open data for individuals associated with their institutions, collections, or archives. However, these projects have brought up ethical concerns around including potentially sensitive personal demographic information, such as gender identity, sexual orientation, race, and ethnicity, in entries in an open knowledge base about living persons. GLAM institutions are thus in a position of balancing open access with ethical cataloging, which should include adhering to the personal preferences of the individuals whose data is being shared. People working in libraries and archives have been increasingly focusing their energies on issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion in their descriptive practices, including remediating legacy data and addressing biased language. Moving this work into a more public sphere and scaling up in volume creates potential risks to the individuals being described. While adding demographic information on living people to open knowledge bases has the potential to enhance, highlight, and celebrate diversity, it could also potentially be used to the detriment of the subjects through surveillance and targeting activities. In this article we seek to investigate the changing role of metadata and open knowledge in addressing, or not addressing, issues of under- and misrepresentation, especially as they pertain to gender identity as described in the sex or gender property in Wikidata. We report findings from a survey investigating how organizations participating in open knowledge projects are addressing ethical concerns around including personal demographic information as part of their projects, including what, if any, policies they have implemented and what implications these activities may have for the living people being described.

Keywords: metadata; ethics; open knowledge; data privacy; linked data; Wikidata; gender

How to cite this article: Lindsey, Nerissa, Greta Kuriger Suiter, and Kurt Hanselman. 2022. Ethical Considerations of Including Gender Information in Open Knowledge Platforms. KULA: Knowledge Creation, Dissemination, and Preservation Studies 6(3). https://doi.org/10.18357/kula.228

Submitted: 25 June 2021 Accepted: 24 January 2022 Published: 27 July 2022

Competing interests and funding: The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Copyright: @ 2022 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Introduction

The trend towards moving to linked open data environments has galleries, libraries, archives, and museums (GLAMs) seeking to leverage open knowledge platforms such as Wikidata to highlight or provide more visibility for traditionally marginalized groups and their work, collections, or contributions. Efforts like Art + Feminism, local edit-a-thons, and larger coordinated GLAM institution-led projects have promoted open knowledge initiatives to a broad audience of participants. For the purposes of this paper, we define open knowledge projects as any project where members of GLAM institutions contribute data about their collections or institutions to structured linked open data platforms that are freely available to anyone on the web to view and in some cases edit. One such open knowledge project, the Program for Cooperative Cataloging (PCC) Wikidata Pilot, has brought together over seventy GLAM organizations to contribute linked open data for individuals associated with their institutions, collections, or archives. This project began in August 2020, when many institutions were physically closed and required many staff to work remotely due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Brought together by the PCC Wikidata pilot project, participants from MIT and San Diego State University collaborated on this paper.

Conversations about linked open data initiatives have focused on workflows and other technical issues, but very little discussion has focused on the ethics of including certain personal demographic information in these open knowledge bases. Personally identifiable information (PII) is defined by the US Department of Labor as information

(i) that directly identifies an individual (e.g., name, address, social security number or other identifying number or code, telephone number, email address, etc.) or (ii) by which an agency intends to identify specific individuals in conjunction with other data elements, i.e., indirect identification. (These data elements may include a combination of gender, race, birth date, geographic indicator, and other descriptors). (US Department of Labor n.d.)

For the purpose of this paper, we will use the term personal demographic information (PDI) to refer specifically to gender identity, sexual orientation, race, and ethnicity. This paper will focus on the inclusion of gender identity in open knowledge projects.

As GLAM institutions contribute information to open knowledge bases like Wikidata, there is a collision of ethics, values, and community norms. The LD4 Ethics in Linked Data Affinity Group is one entity considering the ethical implications of personal information circulating widely. This group is working on developing a code of ethics and a toolkit of resources, both of which will be beneficial for the GLAM community. Having internal policies or adhering to external group policies around the inclusion of PII or PDI in open knowledge bases should be a high concern for GLAM participants, especially if they are considering including information about living persons. This paper will first discuss reparative description and cataloging standards as important efforts to make descriptive practices in GLAM institutions more inclusive and examine ethical considerations of including gender as part of open knowledge work. The paper then provides data from a survey the authors conducted to identify existing policies around these practices for open knowledge projects and gives recommendations informed by the findings.

Background

Reparative Description and Cataloging Standards

In her essay “Praxis for the People: Critical Race Theory and Archival Practice,” Rachel E. Winston (2021, 285) points out some of the problematic history of archival description. She states that

even with attempted “objectivity,” finding aids and descriptions created for archives of People of Color or ethnic communities and authored by someone from outside of that community are often discernable. The outside gaze reveals itself through language. Here, word choice creates barriers to access for those most likely to use and see themselves represented in a particular collection, and intentionality aside, the inclusion of problematic, offensive terminology or the exclusion of informed detail that leads to erasure is troubling.

Efforts to revise past description and create new standards for writing description can be found across GLAM institutions. The practice of revising description to be more inclusive is referred to as reparative description1 or description remediation. Reparative work takes many forms and is happening across the GLAM community. The goal of reparative description work is to create anti-racist, anti-oppressive description (Archives for Black Lives 2019) that will provide better context and representation in GLAM collections. Locating and articulating institutional silences and highlighting underrepresented people is a major part of this work, and more places are writing about and sharing policies around this work. A few examples include Harvard University’s comprehensive “Guidelines for Inclusive and Conscientious Description” (Lellman et al. 2020), New York University’s blog post on updating descriptions related to Japanese American wartime incarceration titled “Righting and (Writing) Wrongs” (O’Neill and Searcy 2020), and, in Canada, the work of museums such as the Western Development Museum, which are striving to update texts to better describe Indigenous populations (Hannah and Scott 2020). These are just a few examples of the work being done in GLAMs to address social inequities in collection descriptions. There is also work being done at the national level.

When it comes to GLAMs and name authority records, the most established database is the Library of Congress Name Authority Cooperative Program (LC/NACO) Authority File (LCNAF), with over ten million authority records (Cannan, Frank, and Hawkins 2019). Name authorities are used across GLAM institutions for consistent description. Authority records provide established forms of names of people and corporations included in bibliographic and collection descriptions. The LCNAF contains information on persons, works, corporate bodies, and more. It is maintained by members of the Name Authority Cooperative Program (NACO), which is a part of the PCC. There are over nine hundred institutions around the world that contribute to the LCNAF (PCC Standing Committee on Training 2020).

In archival description, biographical notes for people and families and historical notes for corporate bodies have often accompanied collection descriptions. The narrative section of a finding aid or resource record provides additional context for the creator or subject of a collection. The standard Encoded Archival Context for Corporate Bodies, Persons, and Families (EAC-CPF), adhered to by the Society for American Archivists, encourages the use of more structured data and the attachment of contextual description to agent records as well as, or in place of, biographical notes in collection records. Adding EAC-CPF agent records to archival records changes how archivists work: instead of writing narratives about people, they can now focus on data points that identify and differentiate individuals from each other.

These expanded description processes are part of a shift in the GLAM metadata landscape from authority control to identity management. “Transitioning to the Next Generation of Metadata,” an OCLC report by Karen Smith-Yoshimura, describes this shift as “the transition to linked data and identifiers” (2020, 3). Some of the changes include moving from original cataloging to entity description, utilizing link management rather than copy cataloging, and including vocabularies from many sources in addition to library authority control (Smith-Yoshimura 2020). Reparative description and identity management should work in tandem to produce information-rich datasets that can be easily shared and understood by machines as well as humans. Even as GLAM workers seek to distill individuals’ lives down into specific data points, they should keep the goals and practices of reparative description in mind to reduce or eliminate any harm that could result from describing certain characteristics of individuals.

At the time of this writing, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020–22 and the impact of the Black Lives Matter movement, description remediation has centered on Black, Indigenous, Hispanic, and other marginalized racial identities. While there is a sea change happening in regard to the study of the history of race, there is also a sea change afoot with regard to gender.

In the early 1990s, there were recommendations made by individual archivists for adding gender neutrality to language used in description. In “Mediating in a Neutral Environment,” Sharon P. Larade and Johanne M. Pelletier stated that updating description should be an ongoing activity based on policies that may change as societal norms do: “the mediating factor in adopting linguistic change is maintaining perspective; it helps to remember that these changes are but steps in a lengthy evolution, not just a passing phase” (1993, 101). Gender fluidity is openly accepted by many young people and traditional definitions of gender and sexuality are being challenged and explored as never before (Diamond 2020), including in many institutions of higher education, where discussions and practices around gender pronouns are common and teachers are learning how to teach “beyond the gender binary” to make their lessons more gender-inclusive (Yarmosky 2019). Creating policies with change in mind is the only way to ensure relevance, and updating description practices to correspond to contemporary understandings of gender is an issue of importance with both personal and political implications.

To gain a more nuanced understanding of gender, one source we can look to is the Gender Unicorn info-graphic. Created by Trans Student Educational Resources, the Gender Unicorn is a drawing of a cartoon unicorn which helps us visualize the complexity of gender. This diagram presents five data points that contribute to one’s gender: gender identity, gender expression/presentation, sex assigned at birth, physically attracted to, and emotionally attracted to. It represents each of these data points as existing on a sliding scale that may change over time.

Name Authorities and Gender Identity

GLAM workers are interested in documenting and accurately describing the full spectrum of gender identity as represented in collections. Knowing details about people’s gender identity assists curators with understanding strengths and gaps within collections and can make material easier to locate for outreach events and exhibits. How, then, should we and do we document this complexity in authority records?

In 2016, the PCC published the “Report of the PCC Ad Hoc Task Group on Gender in Name Authority Records” (Billey et al. 2016). This report includes best practices for the LCNAF community for including gender information in authority records and provides expert guidance, recommendations, and best practices for catalogers. It also discusses standards and thesauri in detail and recommends the Library of Congress Demographic Group Terms (LCDGT)—a controlled vocabulary used to describe the characteristics of two types of entities, the intended audiences of resources and the creators of and contributors to resources—as the thesaurus that best fits the needs of librarians.2 The report also emphasizes the importance of citing sources, whether published or the person being described. Yet, utilizing LCDGT in MARC records according to Resource Description and Access (RDA) rules is of use to trained catalogers, but trained catalogers only. In GLAM institutions there is only a small subset of employees that are able to create authority records for NACO. Working in open knowledge platforms allows many more editors to contribute to descriptions of people. The challenge for catalogers is letting go of the control over these entities. A crowd-sourced description may have many points of compromise and may need to adhere to global definitions and understandings.

As noted above, in both name authority file cataloging and archival description there is a move towards fuller description of people, families, and corporations. The purpose of this practice is to provide more contextual information along with a person’s name; however, there is an inherent risk in doing so. In “More Than a Name: A Content Analysis of Name Authority Records for Authors who Self-Identify as Trans,” Kelly J. Thompson (2016) describes this shift in authority files in detail and warns of the potential harm that catalogers could do by describing people’s gender identity in authority records. She also suggests that linked data or systems like ORCID that allow authors to document their own demographic information could be a preferred method of description practices.

As these changes occur, so do the systems that support them. Since its launch in 2012, Wikidata has become the largest user-editable platform for linked open data. It is easily accessible, anyone can edit it, and it works well with SPARQL (the standard query language for RDF triplestores and linked open data that is available online) for data querying. Wikidata has emerged as the most dynamic and open knowledge base in the world. Wikidata, Wikipedia, and Wikimedia Commons and many more projects and platforms are supported by the Wikimedia Foundation and a global network of passionate volunteers. Conjoining the Wikimedia ecosphere with the world of GLAM cataloging and description is a tremendous opportunity to strengthen and further link descriptions created by a diversity of individuals, subject experts, and volunteers. An important part of this union is a mutual understanding of editing and behavioral norms and sharing of perspectives and goals.

Wikidata Community Guidelines and PDI

When it comes to policy, the Wikimedia community is also radically open and transparent, as evidenced by community-created documentation and consensus-based policy-making. Within the world of Wikimedia projects, there are discussion and talk pages open for all to see and edit. Consensus-building is very important in the Wikimedia community and any active editor can contribute to decisions (Ayers, Matthews, and Yates 2008).

In Wikidata and Wikipedia, there are specific policies for editing information about living persons. First off, who is included in Wikidata or Wikipedia is a matter of policy. Both platforms have notability guidelines, but they are more rigorous for Wikipedia. Wikidata criteria include: the person has a Wikipedia article, there are references about the person in the world, or the person fills a structural need—meaning there is a related Wikidata item that could benefit by being linked to this new entity (Wikidata 2021a).

After one determines notability, there are other policies to know about. The Wikipedia page “Biographies of living persons” provides lengthy guidance on how to create a biography that is “written conservatively and with regard for the subject’s privacy” (Wikipedia 2021). In Wikidata, there is a “Living people” policy that states, “as we value the dignity of living people, the information that we store about them deserves special consideration” (Wikidata 2020).

In Wikidata, there are similar discussions and policy pages about properties. Properties (which have P numbers) are the main way one describes items (which have Q numbers) in Wikidata. There are currently 8,956 properties, which describe over ninety-four million items. A single item will have properties, which in turn have values that create linked data. For instance, the Wikidata item for Janet Mock (Q6153507) has many property statements, including instance of (P31), image (P18), sex or gender (P21), date of birth (P569), occupation (P106), and official website (P856), among others.

When describing a person in Wikidata, there are 156 “personal properties” that may help in providing context and links relevant to that person’s life. Some of these properties have been designated as a “property that may violate privacy.” Examples of properties with this designation are Unmarried partner (P451, likely to be challenged) and Medical condition (P1050, likely to be challenged). Wikidata provides the following guidance for these properties: “when this property is used with items of living people it may violate privacy; statements should generally not be supplied unless they can be considered widespread public knowledge or openly supplied by the individual themselves” (Wikidata 2021b).

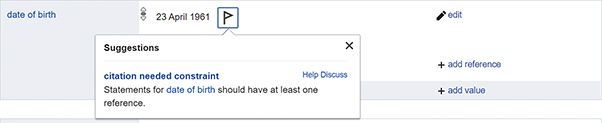

Often these types of properties will have the built-in constraint that a citation must accompany the statement. For instance, P569 (date of birth) requires a reference to be cited when using that property, but P21 (sex or gender) does not, even though it too is a “property that may violate privacy.” It is possible to create a property without a reference citation, but there will be a triangular flag indicating an error next to it (Figure 1). These error signals indicate to other editors that something needs fixing, so it is possible another editor will come along and provide the citation. This is a great example of how Wikidata gives editors nudges towards making the platform better and more accurate.

Figure 1: Date of birth property in Wikidata with pop-up note.

The sex or gender property (P21) is recommended for describing “human: male, female, non-binary, intersex, transgender female, transgender male, agender.” And it is also used for describing “gender identity | gender expression | gender | biological sex | man | woman | male | female | intersex | sex” (Wikidata 2021c). When it comes to the development of policy on P21, one can visit the discussion history and see how the decisions around the property were made. The very first comment is “the label for this is wrong - either it’s sex:male/female/intersex or it’s gender:masculine/feminine/neuter. I’m presuming the former is intended, in which case, should we re-label?” (Wikidata 2013–20). This comment was posted in 2013 and the discussion is ongoing today. The history of the development of this property also considers the global nature of Wikidata. In the discussion on the above question it was pointed out that “apparently some/lots of languages don’t have the concept of male-ness translated properly as a thing independent of human-ness, so we can’t do that. :-(” (Wikidata 2013–20). While there is discussion happening, there is no embargo on using the property, which could be a big takeaway for the GLAM community: even though the policy is not perfect, it still works.

Understanding the policy on using P21 and the discussion behind it could be a good starting point for many GLAM employees who are thinking about contributing this information to open knowledge projects. The challenge is understanding how Wikidata policies and GLAM professional ethics can work together.

Ethical Considerations in Describing Gender

Cultural bias, harmful language, and privacy concerns constitute just a few of the many ethical issues GLAM institutions face across various descriptive contexts, and many librarians and archivists actively engage with these issues in their praxis. In their work on radical empathy in the archives, for instance, Michelle Caswell and Marika Cifor (2016) advocate for a feminist ethics of care as a more inclusive and effective approach for pursuing social justice in archival work, one which would integrate radical empathy into archival practice, including descriptive practices. In general, this theoretical framework represents a shift of the moral responsibility of the archivist towards the people they describe and serve rather than towards collections stewardship. In terms of description, this shift is indicative of the responsibilities that GLAM institutions have towards PDI data and the persons it describes.

There are many issues when it comes to data modelling for gender, such as cultural bias and colonialism, and reparative description therefore includes efforts to decolonize descriptions. Concepts of sex/gender binaries, trans/cis binaries, etc. are steeped in Western normativity. Imposing these ideals on non-Western folks or people who do not conform to these ideals is a sort of colonialism. Kalani Adolpho notes that “the cisgender/transgender binary is a Western construction and to classify gender diverse peoples of other cultures as transgender against their will would be a colonial imposition” (2019, 114), so even the use of the term transgender could be problematic and not inclusive of non-Western and Indigenous gender identities and gender systems. As such, Adolpho (2019) advocates for the use of the terms “gender variant” and “gender diverse,” which are inclusive of transgender people without centering Western notions of gender identity classification or forcing those variant and diverse identities to exist within a cis/trans binary. Adolpho makes note of a number of issues and criticisms in response to the PCC Ad Hoc Task Group’s recommendations on including gender in name authority records (NARs), including “the fixedness of gender, cisnormative and regressive understandings of gender, lack of discussion on currency of source material, imposition of Western gender classification on indigenous gender systems, and ignorance of the fact that most cataloguers do not possess the level of cultural competency that would be required to record gender in NARs” (2019, 116).

In the context of the increased use of demographic terms in NARs, Thomas Whittaker echoes similar concerns over the ethical implications of the PCC recommendations, saying “it is unreasonable to expect that the Library of Congress or the Program for Cooperative Cataloging would require the type of rigid uniformity that would be necessary” and “to assume that catalogers could maintain accurate demographic information in NARs given the fluid nature of identity” (2019, 66). Multiple scholars have called into question whether it is even possible to distill the spectrum of gender identities (which are not static) into a controlled vocabulary from which to choose appropriate terminology. The instructions for recording gender in RDA have also been criticized for reinforcing “regressive conceptions of gender” (Billey, Drabinski, and Roberto 2014, 412), which “continues the work of cisgender and Western hegemony by packaging complex and personal gender identities into static, discrete controlled vocabularies” (Adolpho 2019, 117).

Even though it may be challenging, there may still be a use to cataloging and documenting gender in NARs, and there are some best practices for the GLAM community to follow. The LCDGT thesaurus should be the basis for PDI terms, as per the recommendation of the PCC Ad Hoc Task Group, along with the best practices for recording information about gender in the task group’s report (Billey et al. 2016). This list of best practices emphasizes the importance of self-identification and explicit disclosure.

If gender information is included in Wikidata, one has the ability to query that information via SPARQL. There is a lot of potential (both positive and negative) when querying collections that include PDI about living persons. GLAM communities must recognize that the consequences of including this data could have disproportionate effects on persons from marginalized, minoritized, and/or underrepresented groups. However, there is also the potential to benefit such groups and communities by highlighting their contributions to collections.

Given the multitude of established ethical concerns surrounding PDI in other metadata contexts, it is important to examine how these might apply in an open knowledge platform context. In order to do this, we conducted a survey to gather data around existing policies on PDI in open knowledge projects.

Data Collection

The goal of our research was to identify what kind of PDI members of GLAM institutions that are contributing to open knowledge projects (Wikidata, Wikipedia, Social Networks and Archival Context, etc.) have been adding as part of their work. An additional purpose was to learn about what policies and practices, if any, GLAM staff are following regarding contributing demographic information for living persons (e.g., sex or gender, ethnic group, race, sexual orientation, etc.) to open knowledge projects. Our survey was shared in May 2021 and was open for a little under a month. It was distributed through email discussion lists (i.e., PCC Wikidata Pilot, AUTOCAT, BIBFRAME, OLAC, ARLIS, Society of American Archivists), posted on the Facebook group “Troublesome Catalogers and Magical Metadata Fairies,” and posted on Twitter.

Data collected from our survey is openly available through the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/UTPPN9. We received a total of 126 responses. Of these, twenty-eight respondents indicated that they were not working on any open knowledge projects and were automatically withdrawn from the survey, and twenty-five responses were incomplete. These responses were excluded, leaving seventy-three complete responses to base our analysis on. The majority of the respondents work at institutions in the United States (fifty-six responses), followed by Canada (five), and the United Kingdom (four). Other countries represented by respondents include the Netherlands (one), Italy (two), Israel (one), Germany (two), Brazil (one), and Australia (one). We asked respondents from the United States to indicate which state they were from, and the data represented twenty-two different states.

The majority of respondents work at academic libraries, followed by academic archives or special collections, museums, government archives or special collections, public libraries, and community archives/historical societies. Almost 11 percent3 (n = 8) of the respondents reported working at other types of institutions. Of the seventy-three respondents, sixty-three indicated that they were actively working on open knowledge projects, and ten indicated that they were not actively working on any, but were in the planning stages.

We were interested in knowing what kind of open knowledge projects respondents were working on. A majority of the respondents indicated that they were either working on Wikidata (n = 30, 47 percent) or Wikipedia (n = 20, 31 percent). A small percentage indicated that they were working on Social Networks and Archival Context (SNAC) (n = 8, 13 percent). Other projects that respondents listed (n = 6, 10 percent) were a mix of local bibliographic data or local linked data. We also asked respondents how many people were working (part or full-time) on open knowledge projects at their institution. The question had sixty-six responses, and the majority of them (twenty-one) indicated that they had three to five people working on open knowledge projects, followed by twenty respondents who indicated that only one to two people were working on these kinds of projects. Nine respondents indicated that they had eleven or more people working on these kinds of projects.

Methodology

All of the data analysis was performed in Qualtrics. In order to analyze the data, we used Qualtrics filters to run cross-tabulation on only the completed responses (N = 73). These filters allowed us to include only the respondents who indicated they were working on open knowledge projects or were in the planning phases and to leave out those who did not answer the question. We had one open response question for which we used the Qualtrics TextIQ function to manually code and group the twenty-nine responses based on themes.

Findings

One of the main focal points of our research was to find out if people are including PDI as part of their open knowledge work. The question “Does your institution include personal demographic information for people who are still living as part of the open knowledge project work?” was designed so that respondents could select all the responses that applied: “Sex or gender,” “Ethnic group,” “Race,” “Sexual Orientation,” “We don’t include any of this information,” or “Other, please list.” There were eighty-four recorded answers in total. Twenty-two respondents (26 percent) indicated that they are including sex or gender, fifteen (18 percent) indicated that they are including ethnic group, and twelve (14 percent) indicated that they are including race. Four respondents (5 percent) are including sexual orientation, nineteen (22 percent) indicated that they do not include any of the demographic information listed, and twelve (14 percent) indicated that they include other kinds of demographic information not listed in our question.

We ran a variety of cross-tabulations for some of our survey questions to see if there was any statistical correlation between them. We did not find any statistical significance or relationships between the variables, but they do provide us an opportunity to look at relationships in terms of raw numbers. For instance, we ran a cross-tabulation comparing institution type to see if there was any connection or correlation between type of institution and whether or not it followed any policy pertaining to including personal demographic information. We were interested in seeing if similar institutions had policies or shared similar policies across the different GLAM institution types. The data showed that for the fifty-one total respondents that answered the question “Does your institution follow any policy or policies pertaining to the inclusion of personal demographic information (Sex or Gender, Ethnic Group, Race, Sexual Orientation, etc.) for people who are still living as part of the open knowledge work?,” twenty-six respondents were from academic libraries. Respondents from academic libraries accounted for seven (64 percent) of those that indicated that they had written policies, ten (53 percent) that had unwritten/informal policies, five (56 percent) that had both, and only four (33 percent) that indicated they had no policy (Table 1).

For those respondents that had practices or policies with guidelines for including PDI in open knowledge projects, we asked a follow-up question: “What resources have informed your practices and policies of including or not including personal demographic information as part of your open knowledge work?” This was another “select all that apply” question that included these options: “Published articles,” “Community best practices,” “Workshops,” “Listservs,” “Conferences,” “Word of mouth,” and “Other, please list.” There was a total of 148 recorded responses. Thirty-seven respondents (25 percent) indicated that they use community best practices. Twenty-one respondents (14 percent) indicated that they use both conferences and word of mouth. Twenty respondents (14 percent) indicated they use published articles, and nineteen (13 percent) indicated that they use both workshops and listservs. Eleven respondents (7 percent) indicated that they use some other resources to inform their practice and policies. A couple of responses referenced PCC guidelines and documentation. One response referenced privacy laws such as the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

We asked respondents another follow-up question: “If you include personal demographic information as part of your open knowledge project work, what sources do you use to get this information?” This was a “select all that apply” question that included these options: “ORCID,” “Authority file records,” “Directly from the person being described,” “Institution website,” “Other public website,” “other source, please list,” “social media (Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, etc.).” The question received 114 recorded answers. Twenty-three respondents (20 percent) indicated that they get this information from authority file records. Twenty-two (19 percent) indicated that they get this information directly from the persons being described themselves, and nineteen (17 percent) that they get their information from either an institutional website or another public website. Eleven (10 percent) indicated that they get their information from either ORCID or some other source, which they listed. Finally, only nine (8 percent) indicated that they used social media (Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, etc.). As a follow-up to this question, we asked: “Do you include references for any personal demographic information that you include in your description as part of your open knowledge work?” for which there were forty-two total responses. Twenty-eight (67 percent) indicated that they are including references, and fourteen (33 percent) indicated that they are not.

We wanted to know if there was any relationship between people who were including personal demographic information and whether or not they had any type of policy that they were following about the inclusion of these properties. We asked the question “Does your institution include personal demographic information for people who are still living as part of the open knowledge work? Check all that apply,” which received eighty-four recorded responses. Twenty-two respondents (26 percent) include sex or gender information, fifteen (18 percent) include ethnic group, twelve (14 percent) include race, and four (5 percent) include sexual orientation. Nineteen (23 percent) indicated that they did not include any of these properties at all, and twelve (14 percent) selected “other.” Among those that chose “other,” the responses were varied, with some respondents indicating that they are not consistent in which properties they include and others indicating properties like religion or political party. We ran a cross-tabulation for this question about what demographic information people were including against the question about whether or not respondents had a policy (Table 2). Surprisingly, the properties included by the lowest number of respondents (race and sexual orientation) also had the highest percentage of respondents indicate that they have a written policy for those particular properties. Of the twelve respondents who indicated they included the race property, 50 percent indicated that they had a written policy about including demographic information. For the four respondents who indicated that they include sexual orientation, 75 percent indicated that they have a written policy.

We cross-tabulated these responses against the questions about what types of properties people were including to see if there were any properties that our respondents were more likely to include references for (Table 3). It was encouraging to us that 100 percent of respondents included references for sexual orientation. In Wikidata, the sexual orientation property (P91) has a “citation needed constraint,” so if respondents are providing this information in Wikidata they are following the guidelines of the Wikidata community (Wikidata 2021d). Ninety-one percent of respondents indicated that they were including references for the property sex or gender (P21). In Wikidata, P21 does not require a citation for inclusion. Lower percentages of respondents indicated that they include references for race and ethnic group properties, which we found surprising since in Wikidata the property ethnicity group does require a citation.

We asked another question specific to those who are including sex or gender as part of their work: “If you include information about Gender as part of the open knowledge project work, do you use any kind of controlled vocabularies (e.g. Homosaurus, Library of Congress demographic Group Terms, or others) to determine what term you use?” Of the thirty-eight respondents who answered this question, sixteen (42 percent) indicated that they are using controlled vocabularies, and fourteen (37 percent) indicated that they are not. Eight (21 percent) selected “other,” and the responses were varied. Some referred to using Wikidata items to express gender, while others mentioned using the term used by the person being described. One response specifically brought up the issue of constraints around this in Wikidata, noting that “in Wikidata we feel constrained by what’s there, which is imperfect so we have an informal policy of just listing male/female/nonbinary and not trying to say ‘transgender man’ because that seems like a hot mess.”

We were particularly interested in the responses to our question “By including PDI as part of your open knowledge project, what is your desired outcome?” This was an open-ended question for which we got twenty-nine responses. We identified two predominant themes among the open responses. The majority of respondents talked about improving discoverability in general around these demographic properties. However, some responses talked about improving discoverability specifically as it related to increasing representation around these demographic properties. For example, one respondent indicated that their desired outcome was “to enhance discovery based on demographic groups, for instance, to allow readers to find all works by women authors on a certain subject.” The second predominant theme was respondents’ emphasis on highlighting or bringing awareness to inequities within their collections or bringing awareness of inequities in general to promote social justice.

We asked the question “Do you use any specific queries (SPARQL, or others) related to this personal demographic data that serve a purpose either for research or some other internal use?” Among the forty respondents that answered that question, only nine (23 percent) indicated that they were using specific queries. Thirty-one (78 percent) indicated that they were not. As a follow-up question, we asked: “Which personal demographic data queries do you use?” It was supposed to be a “select all that apply” question, but it was structured as a “choose one” option until someone reported the issue and we fixed it, so that caused a large percentage of the nine respondents to choose “other” and write out which properties they are using the queries for. Of the four that wrote out their responses, two indicated that they had queries for all of the property types in question. Of the other two, one wrote that they have queries for sex or gender, ethnic group, and sexual orientation. The other wrote that they have queries for sex or gender and ethnic group. Among the other respondents who chose a single option, 33 percent indicated that they had queries for sex or gender and 22 percent indicated that they had queries for ethnic group. It is unclear how accurate these numbers are due to the survey design flaw that got corrected halfway through the response period.

Very few respondents answered the question “Are you using data from these queries to inform any Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion initiatives at your institution?” Of the eight respondents, five (63 percent) indicated that they are not using queries for this purpose, and three (38 percent) indicated that they are. For those who are using the queries for EDI initiatives, it would be interesting to know how they are using that data to inform policy.

Discussion

The data we collected brings up a number of interesting questions that we think would be worth investigating with further research, including why some institutions do not include PDI and how the subjects of this open data might feel about this information. Given the large numbers of respondents who indicated that they were including PDI, the low number of comprehensive responses about what respondents were hoping to accomplish by including that data was interesting. Does this mean that respondents do not have clear goals for engaging with open knowledge work? It was also curious, given how many people indicated that they were including this information to highlight marginalized groups or inequities in collections, that there were so few responses indicating that this work was at all related to any equity, diversity, and inclusion initiatives. We were surprised that a good portion of respondents indicated that they do not include any PDI as part of their open knowledge work. It would have been enlightening if we had a follow-up question asking specifically why they do not include that information. It would give us a better sense of whether they were taking an ethical stance or had other reasons for not adding it. We definitely encountered some limitations with our survey instrument that prevented a cross-tabulation of certain questions. If we had made some questions “choose one answer only,” it would provide better analysis. An interesting follow-up line of research might be to develop a way to survey individuals reflected in these open knowledge Wikidata items and perhaps do some focus groups on how they feel about the information about them being collected and encoded in these open knowledge bases.

What Is the Harm?

In “Principles and Concepts in Information Ethics,” Burgess (2019, 1) asserts that “if, figuratively speaking, ethics is the story of what it means to be good and all the ways humans remain bad, then information ethics is the story of the good that can be accomplished with information, and all the ways it may be used to harm.” Based on the data we collected, it is clear that there are GLAM staff across all institution types that are including PDI as part of their open knowledge work and that not all of them have policies guiding them on the ethical inclusion of this information. Given these findings, we would like to investigate the potential harm that including this personal demographic information can cause, with a focus on sex or gender in particular.

Much work has been done investigating the harm that language can cause in various contexts. In her article about archival descriptions of LGBTQ materials, Erin Baucom (2018, 70) discusses the harm that can be caused by not using language or terminology that members of a specific community use to describe themselves and how this can lead to negative self-perceptions and other detrimental outcomes for people’s mental well-being. Baucom goes into detail about the deficiencies of existing Library of Congress Subject Headings that are outdated and at times derogatory. Adding further complexity is that there are ever-changing understandings and definitions, and there are times when the “LGBTQ community does not always internally agree on terminology” (Baucom 2018, 71).

The data from our survey showed that less than a quarter of respondents use the people being described as the source of the demographic information being included in descriptions for those people. This, on some levels, could be seen as a violation of privacy. For example, according to Grant Campbell and Scott R. Cowan (2016, 501), “privacy, as an operationalized concept, consists not simply of solitude or invisibility but an individual’s power to modulate the extent of his or her self-revelation in specific circumstances.” Although some people might understand that inclusion of PDI in open knowledge projects often leads to uncontrollable circulation of that information, making it nearly impossible to retract or delete the information, many may not. Only through explicit buy-in, meaning permission or consent directly from an individual, can GLAM professionals be sure they are not violating a person’s privacy. Encoding PDI into open knowledge bases without the explicit buy-in of the living persons being described takes away individuals’ power to decide what information about themselves they want out in an open linked data environment.

There is additional harm that can be caused by encoding information for gender information in a publicly accessible knowledge base, which can allow bad actors to quickly collocate and target people of specific demographic groups. Amber Billey (2019, 11) outlines some of these risks in her article “Just Because We Can, Doesn’t Mean We Should,” pointing out that sharing an email address could put a person at risk for identity theft and that recording a person as transgender could put that person’s safety at risk. The worldwide audience of open knowledge projects means that there are increased risks for discrimination and hate targeting specific gender identities. As VAWnet (n.d.) documents, “transgender individuals and communities experience shocking amounts of violence and discrimination.” Imagine if anti-trans rights bigots learned how to weaponize SPARQL to identify all the trans-identifying people who work at a specific institution and used that structured public information to target, dox, or harass them.

In her work on barriers to ethical name modelling in current linked data encoding, Ruth Kitchin Tillman (2019) specifically addresses the harm of people deliberately using dead names or other names that living persons no longer go by and how this information can then be reused and referenced elsewhere, spreading the harm even further. There is further concern about how governments might use this information, especially in countries where there are still strict anti-gay and anti-trans laws, some of which are punishable by imprisonment, corporal punishment, and, in some extreme cases, death. According to the latest Trans Legal Mapping report (Chiam et al. 2020), it is not legal to change your gender in at least forty-seven United Nations countries. In the United States, we are still struggling to pass the Equality Act (Congress.gov 2021), which would provide the same protections to LGBTQ+ individuals as the Civil Rights Act, in the Senate, despite widespread agreement that this type of protection should be passed (DeBonis 2021). Including PDI in open knowledge projects could potentially cause harm and lead to detrimental outcomes for the people in question; for instance, including this information could out people from minoritized and underrepresented groups who may then have their jobs put in jeopardy. There could also be other privacy issues especially pressing for living persons, such as the inadvertent leaking of confidential medical information. If an author has only ever identified as a woman and has never disclosed publicly that they were trans, encoding data in a public database that lists that person as a trans woman could be an inadvertent leaking of that person’s medical information. This could lead to scenarios where people might face repercussions as a result of having identity and demographic information publicly associated with them.

Policy Recommendations

It is important that GLAM members understand that when they are adding PDI to items describing living persons that it is not a neutral task, and it inherently comes with risks of harm. The safest and arguably most ethical practice is to avoid including PDI as part of your open knowledge work for living persons. However, given the reality that PDI is being included, we have some general policy recommendations for where we are right now given the limitations of the open knowledge platforms that people are working with. Long et al. (2017, 123) discuss how problems and solutions are ever changing and how, instead of focusing on a static solution, people should focus on the best solution for the time. They urge librarians, archivists, and information scientists to dispel the myth of neutrality by explicitly documenting their framing and assumptions when creating metadata standards and argue that, to further transparency in creating standards, creators should publish their framing alongside their standard (Long et al. 2017, 123). Their framework can be applied to open knowledge metadata creation as well.

We recommend that people take the time to learn about the gender, ethnicity, and other related properties in Wikidata and follow and participate in the discussions that lead up to decision-making for the Wikidata community. People should also take the time to learn about data modelling and compare notes with other institutions to see what data elements they are including. Take the time to create internal policies or guidelines for which properties you will include that always need a reference citation. Add a place for donors to indicate pronouns and how they would like to be identified in terms of race, ethnicity, and gender in gift agreements. If you are unsure of a living person’s preferences, ask them directly or do not include that information. Include verifiable references for all PDI statements you include in Wikidata. Finally, focus your energies by determining which SPARQL queries would most effectively assist with diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives so that you focus only on properties that are most salient to the community that you are trying to highlight or bring awareness to.

Conclusion

As the trend towards linked open data environments and using open knowledge platforms continues, ethical quandaries about what information is included in these platforms will become more salient. As we enter this larger metadata ecosystem, which is harder for institutions to centrally control, more emphasis needs to be placed on coordinating with the broader linked data community on guidelines and policies around what information is included in these systems. GLAM professionals are going to need to work in tandem with Wikidata practitioners from outside GLAM organizations to understand the implications and impact of practices for including PDI in these systems. Our research indicates that some GLAM practitioners are including PDI as part of their open knowledge work, and this article urges those practitioners to be aware of and make good faith efforts to mitigate some of the ethical issues we have outlined in this paper. While more research could be done to quantify the direct harm that comes from including PDI information in open knowledge ecosystems, the risk of harm is something we all need to keep in mind. Many GLAM professionals who are including this data do not have solid justification for why it is needed or why they are doing it. We need to be more thoughtful and deliberate about balancing the metadata needs of our organizations with the new possibilities that linked open platforms allow, especially around practices that could potentially harm people.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Violet Fox and Christine Malinowski for reviewing and providing feedback and guidance for our survey. We would also like to thank Dr. Angelique Blackburne for meeting with us to discuss tips for data analysis and providing feedback on the data analysis draft. We would like to thank Christine Malinowski for also meeting with us to discuss research data management protocols for depositing the data collected as part of this project. Thanks to all that assisted in editing: Phoebe Ayers, Kate Holvoet, and Tad Suiter.

References

Adolpho, Kalani. 2019. “Who Asked You? Consent, Self-Determination, and the Report of the PCC Ad Hoc Task Group on Gender in Name Authority Records.” In Ethical Questions in Name Authority Control, edited by Jane Sandberg, 111–31. Sacramento, CA: Library Juice Press.

Archives for Black Lives in Philadelphia’s Anti-Racist Description Working Group. 2019. Archives for Black Lives in Philadelphia Anti-Racist Description Resources. https://archivesforblacklives.files.wordpress.com/2019/10/ardr_final.pdf.

Ayers, Phoebe, Charles Matthews, and Ben Yates. 2008. How Wikipedia Works And How You Can Be a Part of It. No Starch Press. http://www.howwikipediaworks.net/.

Baucom, Erin. 2018. “An Exploration into Archival Descriptions of LGBTQ Materials.” The American Archivist 81 (1): 65–83. https://doi.org/10.17723/0360-9081-81.1.65.

Billey, Amber. 2019. “Just Because We Can, Doesn’t Mean We Should: An Argument for Simplicity and Data Privacy with Name Authority Work in the Linked Data Environment.” Journal of Library Metadata 19 (1–2): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/19386389.2019.1589684.

Billey, Amber, Emily Drabinski, and K. R. Roberto. 2014. “What’s Gender Got to Do with It? A Critique of RDA 9.7.” Cataloging & Classification Quarterly 52 (4): 412–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639374.2014.882465.

Billey, Amber, Matthew Haugen, John Hostage, Nancy Sack, and Adam L. Schiff. 2016. “Report of the PCC Ad Hoc Task Group on Gender in Name Authority Records.” Program for Cooperative Cataloging. https://www.loc.gov/aba/pcc/documents/Gender_375%20field_RecommendationReport.pdf. Archived at: https://perma.cc/8WVJ-RFZW.

Burgess, John T. F. 2019. “Principles and Concepts in Information Ethics.” In Foundations of Information Ethics, edited by John T. F. Burgess, Emily J. M. Knox, and Robert Hauptman, 1–16. Chicago: ALA NealSchuman.

Campbell, Grant, and Scott R. Cowan. 2016. “The Paradox of Privacy: Revisiting a Core Library Value in an Age of Big Data and Linked Data.” Library Trends 64 (3): 492–511. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2016.0006.

Cannan, Judith P., Paul Frank, and Les Hawkins. 2019. “LC/NACO Authority File in the Library of Congress BIBFRAME Pilots.” Journal of Library Metadata 19 (1–2): 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/19386389.2019.1589693.

Caswell, Michelle, and Marika Cifor. 2016. “From Human Rights to Feminist Ethics: Radical Empathy in the Archives.” Archivaria 81 (Spring): 23–43. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/687705.

Chiam, Zhan, Sandra Duffy, Matilda González Gil, Lara Goodwin, and Nigel Timothy Mpemba Patel. 2020. Trans Legal Mapping Report 2019: Recognition Before the Law. 3rd ed. Geneva: ILGA World. https://ilga.org/trans-legal-mapping-report. Archived at: https://perma.cc/V3RD-C8NV.

Congress.gov. “H.R.5 - 117th Congress (2021-2022): Equality Act.” Accessed March 17, 2021. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/5.

DeBonis, Mike. 2021. “The Push for LGBTQ Civil Rights Stalls in the Senate as Advocates Search for Republican Support.” Washington Post, June 20, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/senate-lgbtq-equality-act/2021/06/19/887a4134-d038-11eb-a7f1-52b8870bef7c_story.html. Archived at: https://perma.cc/SF42-CAUV.

Diamond, Lisa M. 2020. “Gender Fluidity and Nonbinary Gender Identities Among Children and Adolescents.” Child Development Perspectives 14 (2): 110–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12366.

“Gender Unicorn.” n.d. Trans Student Education Resources (blog). Accessed June 17, 2021. https://transstudent.org/gender/. Archived at: https://perma.cc/YFW7-CHEG.

Hannah, Kaiti, and Liz Scott. 2020. “Language Remediation Project Underway at the Western Development Museum: Answering TRC Calls to Action #43 and #67.” Western Development Museum. https://wdm.ca/2020/01/16/language-remediation-project-underway-at-the-western-development-museum-answering-trc-calls-to-action-43-and-67/. Archived at: https://perma.cc/U8YV-UXKV.

Larade, Sharon P., and Johanne M. Pelletier. 1993. “Mediating in a Neutral Environment: Gender-Inclusive or Neutral Language in Archival Descriptions.” Archivaria 35 (Spring): 99–109. https://archivaria.ca/index.php/archivaria/article/view/11889.

Lellman, Charlotte, Hanna Clutterbuck-Cook, Amber LaFountain, and Jessica Sedgwick. 2020. “Guidelines for Inclusive and Conscientious Description.” Center for the History of Medicine: Policies and Procedures Manual. Boston, MA: Center for the History of Medicine, Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine. Harvard University Wiki. https://wiki.harvard.edu/confluence/display/hmschommanual/Guidelines+for+Inclusive+and+Conscientious+Description. Archived at: https://perma.cc/JF7P-3LXW.

Linked Data for Production: Pathway to Implementation (LD4P2). 2021. Ethics in Linked Data Affinity Group. https://wiki.lyrasis.org/display/LD4P2/Ethics+in+Linked+Data+Affinity+Group. Accessed November 29, 2021.

Long, Kara, Santi Thompson, Sarah Potvin, and Monica Rivero. 2017. “The ‘Wicked Problem’ of Neutral Description: Toward a Documentation Approach to Metadata Standards.” Cataloging & Classification Quarterly 55 (3): 107–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639374.2016.1278419.

Mizota, Sharon. 2021. “Change Is Good: Navigating Wikidata as a Controlled Descriptive Vocabulary.” Descriptive Notes (blog), March 30, 2021. https://saadescription.wordpress.com/2021/03/30/change-is-good-navigating-wikidata-as-a-controlled-descriptive-vocabulary/. Archived at: https://perma.cc/8GRK-5HH5.

O’Neill, Shannon, and Rachel Searcy. 2020. “Righting (and Writing) Wrongs: Reparative Description for Japanese American Wartime Incarceration.” The Back Table (blog), New York University Libraries. https://wp.nyu.edu/specialcollections/2020/12/11/righting-and-writing-wrongs-reparative-description-for-japanese-american-wartime-incarceration/.

Program for Cooperative Cataloging (PCC) Standing Committee on Training. 2020. “NACO Participants’ Manual.” Program for Cooperative Cataloging. https://www.loc.gov/aba/pcc/naco/documents/NACOParticipantsManual.pdf.

Smith-Yoshimura, Karen. 2020. Transitioning to the Next Generation of Metadata. Dublin, OH: OCLC Research. https://doi.org/10.25333/RQGD-B343.

Society of American Archivists. 2021. “Reparative Description.” Dictionary of Archives Terminology. https://dictionary.archivists.org/entry/reparative-description.html#:~:text=n.,characterize%20archival%20resources%20(View%20Citations).

Tillman, Ruth Kitchin. 2019. “Barriers to Ethical Linked Data Name Authority Modeling.” In Ethical Questions in Name Authority Control, edited by Jane Sandberg, 243–60. Sacramento, CA: Library Juice Press.

Thompson, Kelly J. 2016. “More Than a Name: A Content Analysis of Name Authority Records for Authors Who Self-Identify as Trans.” Library Resources & Technical Services 60 (3): 140–55. https://doi.org/10.5860/lrts.60n3.140.

US Department of Labor. n.d. “Guidance on the Protection of Personal Identifiable Information.” Accessed June 21, 2021. https://www.dol.gov/general/ppii. Archived at: https://perma.cc/WBP2-WEU6.

VAWnet. n.d. “Violence Against Trans and Non-Binary People.” National Resource Center on Domestic Violence. https://vawnet.org/sc/serving-trans-and-non-binary-survivors-domestic-and-sexual-violence/violence-against-trans-and.

Whittaker, Thomas A. 2019. “Demographic Characteristics in Name Authority Records and the Ethics of a Person-Centered Approach to Name Authority Control.” In Ethical Questions in Name Authority Control, edited by Jane Sandberg, 57–68. Sacramento, CA: Library Juice Press.

Wikidata. 2013–20. “Wikidata:Property talk:P21/Archive 1.” https://www.wikidata.org/w/index.php?title=Property_talk:P21/Archive_1&oldid=1437838048.

Wikidata. 2020. “Wikidata:Living people.” Last modified August 4, 2020. https://www.wikidata.org/w/index.php?title=Wikidata:Living_people&oldid=1246409841.

Wikidata. 2021a. “Wikidata:Notability.” Last modified June 14, 2021. https://www.wikidata.org/w/index.php?title=Wikidata:Notability&oldid=1441483998.

Wikidata. 2021b. “Wikidata:Property that may violate privacy.” Last modified June 4, 2021. https://www.wikidata.org/w/index.php?title=Q44601380&oldid=1434739395.

Wikidata. 2021c. “sex or gender (P21).” Last modified June 8, 2021. https://www.wikidata.org/w/index.php?title=Property:P21&oldid=1437832753.

Wikidata. 2021d. “sexual orientation (P91).” Last modified June 4, 2021. https://www.wikidata.org/w/index.php?title=Property:P91&oldid=1434829665.

Wikipedia. 2021. “Wikipedia:Biographies of living persons.” Last modified June 25, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Wikipedia:Biographies_of_living_persons&oldid=1030375913.

Winston, Rachel E. 2021. “Praxis for the People: Critical Race Theory and Archival Practice.” In Knowledge Justice: Disrupting Library and Information Studies Through Critical Race Theory, edited by Sofia Y. Leung and Jorge R. Lopez-McKnight, 283–98. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/11969.003.0020.

Yarmosky, Jessica. 2019. “‘I Can Exist Here’: On Gender Identity, Some Colleges are Opening Up.” NPR, March 21, 2019. https://www.npr.org/2019/03/21/693953037/i-can-exist-here-on-gender-identity-some-colleges-are-opening-up. Archived at: https://perma.cc/7HL3-5QLG.

Footnotes

1 The Society of American Archivists (2021) defines reparative description as “remediation of practices or data that exclude, silence, harm, or mischaracterize marginalized people in the data created or used by archivists to identify or characterize archival resources.”

2 However, the authors recognize that some institutions use alternative thesauri such as the Homosaurus, an international linked data vocabulary of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) terms maintained by the Digital Transgender Archive. These institutions prefer Homosaurus because it uses terms that the communities represented use to describe themselves, which makes for more appropriate description.