TEACHING REFLECTION

Getting Scrappy in the Classroom During COVID-19: Collaboration, Open Educational Resources, and Hands-on Learning for Humanities Students

Elizabeth Bassett

University of British Columbia

Heather Dean

University of Victoria

Andrea Korda

University of Alberta, Augustana Faculty

Mary Elizabeth Leighton

University of Victoria

Vanessa Warne

University of Manitoba

This teaching reflection, co-authored by two librarians and three instructors, offers a case study in collaborative assignment design and argues for the value of both collaboration as an instructional model and digital exhibitions as open educational resources. It explores how the transition to remote curating, learning, and teaching prompted by COVID-19 occasioned changes in how we curated exhibitions, on the one hand, and developed learning opportunities for students, on the other hand. Focused on a digital exhibition of nineteenth-century scrapbooks and the integration of scrapbooking—as a hands-on activity and a topic of scholarly inquiry—into three courses across two disciplines (English and art history), it also provides a model of how librarians and instructors might collaborate on assignment and course development and scaffold such collaboration into assignment and course design. The reflection includes assignments and rubrics as well as examples of students’ work. It concludes with a series of recommendations for librarians and instructors who wish to collaborate.

Keywords: remote learning; experiential learning; primary source literacy; digital exhibitions; open educational resources; collaboration; COVID-19

How to cite this article: Bassett, Elizabeth, Heather Dean, Andrea Korda, Mary Elizabeth Leighton, and Vanessa Warne. 2022. Getting Scrappy in the Classroom During COVID-19: Collaboration, Open Educational Resources, and Hands-on Learning for Humanities Students. KULA: Knowledge Creation, Dissemination, and Preservation Studies 6(1). https://doi.org/10.18357/kula.222

Submitted: 6 July 2021 Accepted: 6 October 2021 Published: 28 February 2022

Competing interests and funding: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Copyright: @ 2022 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

How might scholars, archivists, and librarians, working collaboratively across disciplines, institutions, and professional backgrounds, create and teach with open educational resources (OERs) in support of experiential, collections-based learning? This essay shares an assignment developed for remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic that responded to both institutional challenges and instructional opportunities. The assignment, which was supported by an open-access digital exhibition on nineteenth-century scrapbooks at the University of Victoria (UVic) Libraries, asked undergraduates to creatively engage with historical scrapbooks and databases of digitized nineteenth-century newspapers and periodicals. Working with the exhibition, students increased their knowledge of a historical practice and strengthened their material and digital literacy—this despite their temporary loss of in-person access to libraries, archives, galleries, and museums. To extend their engagement with the materials beyond reading and viewing the exhibition, students created their own scrapbook pages by cutting up digitized copies of nineteenth-century print materials and pasting their “scraps” into new formations. While developed for online learning in literature and art history classes, this assignment models the use of open content as a starting point for rich and accessible experiential learning in post-COVID-19 classrooms. In doing so, the assignment demonstrates how OER materials developed by librarians and archivists can become potential catalysts for assignments and opportunities for information literacy instruction that exceed the bounds of the classroom or the archives.

Despite enjoying unwavering popularity since the nineteenth century, scrapbooking practices have never been fully welcomed into the academic realm. Like commonplace books, which were assembled by “copy[ing] quotations and commonplaces useful for argumentation and self-education,” scrapbooks were regarded by many Victorians as valuable resources of compiled information (Mecklenburg-Faenger 2012, par. 10, 15). However, scrapbooks acquired an additional and widespread reputation for being “gossipy, self-interested, and poorly organized volumes—the feminine opposite of the masculine commonplace book” (Mecklenburg-Faenger 2012, par. 18), a dismissive attitude that, as Amy Mecklenburg-Faenger argues, lingers in academia today (par. 3).

Adding to the growing body of literature that challenges this attitude, this article highlights the value of bringing scrapbooking practices into the university classroom.1 In particular, we emphasize the value of scrapbooking for instructors looking to incorporate the “5R activities”—retaining, revising, remixing, reusing, and redistributing—that are used to define the “open” in “open content” and “open educational resources” (Wiley n.d.). As Ellen Gruber Garvey explains in Writing with Scissors: American Scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance, scrapbooks, by their nature, endorse “an ideal of reuse and recirculation, of making the old continually new” (2012, 36). Further, in a chapter titled “Reuse, Recycle, Recirculate” (perhaps the 3R activities of scrapbooking), Garvey writes, “clipping and saving the contents of periodicals in scrapbooks is a form of active reading that shifts the line between reading and writing. Readers become the agents who make or remake the meaning and significance of their saved items” (2012, 47). By incorporating scrapbooking practices into the classroom, instructors can create opportunities for students to demonstrate and strengthen their active reading skills.

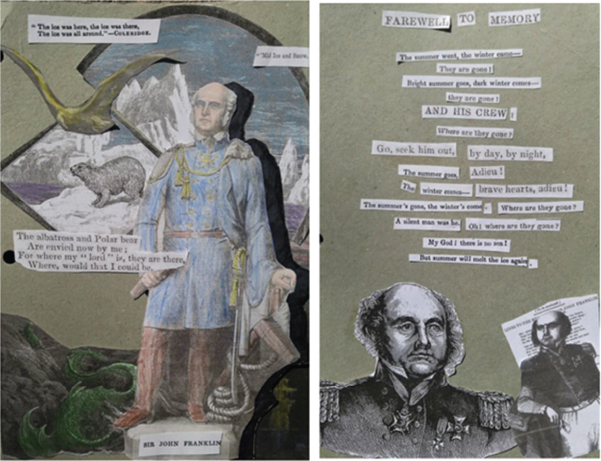

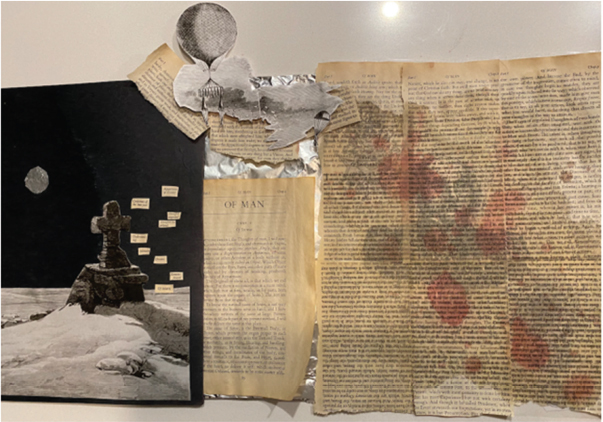

The scrapbook pages shown below (Figures 1 and 2) represent our students’ creative and critically sophisticated work. The first example shows how some of the structures of the nineteenth-century periodical page were retained, with the masthead of The Girl’s Own Paper (a popular Victorian periodical aimed at a readership of young women) pasted at the top centre of the page on the left-hand side, surrounded by columns of text to the right and the left. But these structures are also revised, with scraps of text and pictures remixed and reused to examine how one particular theme, in this case ancient Egypt, was represented in the periodical’s pages. The second example retains less of the periodical page’s original structure, instead remixing textual scraps to create a collage poem on the death of Sir John Franklin while reusing periodical illustrations to reflect on and redistribute visual representations of Franklin. As these and other examples of our students’ work show, retaining, revising, remixing, reusing, and redistributing the pages of nineteenth-century periodicals offer hands-on, experiential ways for students to learn about Victorian periodicals and culture while also improving their digital and material literacy.

Figure 1: Scrapbook pages by Kalea Raposo for “Ella Hepworth Dixon’s The Story of a Modern Woman and the Egypt of Victorian Girls’ Culture.”

Figure 2: Scrapbook pages by Sean Hetherington featuring a collage poem by Hetherington on the death of Sir John Franklin.

In what follows, the librarian authors who supported the assignment’s design reflect on the development of the digital exhibition of nineteenth-century scrapbooks that informed the assignment and propose that digital exhibitions, more generally, constitute OERs and have significant pedagogical value. The instructors then share three iterations of this assignment, our reflections on designing the assignment—which was a collaborative process involving the librarians and all three instructors—and some of the assignment’s results, explaining how hands-on crafting, supported by librarians’ expertise, increased student engagement and enhanced distanced learning during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.2 Indeed, such experiential learning opportunities model both collaborating and creative making as important ways of learning—and of teaching. Together, we advocate assignment design that brings together librarians and instructors in similarly collaborative and creative ways, and we encourage the wide adoption of assignments that expand students’ digital, primary source, and historical literacy as well as their creativity.

Open Educational Resources and Collaborative Teaching and Learning

First defined at a 2002 forum organised by UNESCO on Open Courseware in Higher Education, OERs “are learning, teaching and research materials in any format and medium”—digital or otherwise—”that reside in the public domain or are under copyright that have been released under an open license, that permit no-cost access, re-use, re-purpose, adaptation and redistribution by others” with no or limited restrictions (UNESCO 2019). OERs support open education and are part of a broader open movement that includes, for example, open access and open data. Libraries are increasingly playing an important role in advocating for and advancing the OER movement, as identified in the Ontario Council of University Libraries’ (OCUL) White Paper on Open Educational Resources (2017) and the Association of Research Libraries’ (ARL) Spec Kit 351: Affordable Course Content and Open Educational Resources (2016). Both identify the importance of libraries in this work, as the OCUL White Paper articulates, “primarily around the provision of technical and infrastructure services, education, and training support” (2017, 4). Interestingly, within the professional literature, discussion regarding OERs often stops short of identifying the library as a creator (or author) of OERs as realized through exhibitions. However, there are numerous examples of cultural heritage organizations creating OERs. For example, the OER Commons, created by the Institute for the Study of Knowledge Management in Education (ISKME), provides access to a number of digital collections and exhibitions created by galleries, libraries, archives, and museums (also known as GLAM institutions), such as the National Library of Medicine, the Maryland Science Center, the Digital Public Library of America, and the American Museum of Natural History.3

As illustrated by the number of GLAM institutions contributing to the OER Commons, libraries contribute to learning and teaching, and librarians and archivists create educational resources. We propose that the resources created and provided by libraries and archives—especially when accessible online—should be understood and valued as OERs. Though not typically treated this way, these resources are both open and educational, and when productively paired with course design, they result in meaningful teaching and learning. We learned this lesson from a collaboration during the 2020–21 academic year. This collaboration demonstrated that OERs are not always online textbooks—or even necessarily resources made purposefully for the classroom. Any resource that is out there in the world and accessible to students might be considered an “open educational resource” once it is brought to life in the classroom, animated by the knowledge of experts and the engagement of students.

The shift to remote learning pushed instructors to find new resources for the classroom—ones suited to remote instruction—and also to look to each other as collaborators and supports as they reinvented their teaching methods. At the same time, librarians and archivists who were shut out of libraries and archives were prompted to reimagine how they might share their resources with the public in a remote environment. In the case of the authors of this article—three faculty members from three institutions (the Universities of Victoria, Manitoba, and Alberta) and two librarian archivists at the University of Victoria’s Special Collections and University Archives—these conditions led to a productive collaboration that enhanced students’ primary source literacy through an innovative experiential activity.4

This assignment, then, is grounded in collaboration. Facing a steep learning curve in adapting to new online teaching environments and familiarizing themselves with online teaching tools, instructors turned to useful resources about online teaching such as Pedagogies of Care (2020), Cathy Davidson’s HASTAC blog post on “Designing a Fall Online Course” (2020), James Skidmore’s tips for online teaching (2020), and Jesse Stommel’s “How to Build an Online Learning Community: Six Theses” (2020). But they also turned to one another, making plans to connect scholars through online conversations about Victorian culture. The result was a year-long series titled Crafting Communities: A Series of Victorian Object Lessons & Scholarly Exchanges in COVID Times, which brought together professors, librarians, curators, crafters, artists, and students.

Two of the workshops in the series, on Victorian scrapbooking and primary source literacy, were developed and led by Dean and Bassett and informed the design of the “Getting Scrappy” assignment. Additional projects on scrapbooking prompted the instructors to introduce scrapbooking into their classrooms: Bassett’s already-planned and in-progress digital exhibition of UVic Special Collections’ scrapbook holdings (which shaped the development of Dean and Bassett’s Crafting Communities pedagogy workshop on scrapbooks) and an online event on nineteenth-century scrapbooking hosted by the University of Derby as part of the UK’s Being Human: A Festival of the Humanities (which introduced the instructors to historians Cath Feely and Freya Gowrley and artist Daniel Fountain [2021]). Bassett’s online exhibition provided access to digital sources; Feely’s online session modeled how to integrate hands-on making by artists and historical contextualizing by historians in a session aimed at a general audience and also connected us with Fountain, from whom the instructors commissioned a bespoke how-to video on cut-and-paste collage techniques. Moreover, Leighton’s long-standing collaboration with Dean in facilitating students’ introduction to and use of Special Collections (including student-curated in situ library exhibitions) helped the instructors to imagine an important teaching role for Dean and Bassett in students’ learning.

Designing a Digital Exhibition to Support Remote Learning Opportunities

Cultural heritage institutions at once safeguard rare and unique materials over the long term and provide access to these resources in the present. Instruction is an important method of proactively encouraging access to collections, and special collections and archives are often appreciated for their unique contributions to student learning. Professional ethics emphasize the importance of providing access to collections through outreach and instruction. For example, the Association of College and Research Libraries’ “Code of Ethics for Special Collections Librarians” (2020) notes, “special collections practitioners work to forge connections between collections and as diverse a community of users as possible, striving to find points of relevance that foster engagement at a multitude of levels.” With digital collections and exhibitions, cultural heritage institutions provide unprecedented access to the resources in their care to an ever-expanding audience.

Archivists and librarians increasingly assume educator roles, supporting students working with rare materials and mentoring emerging information professionals enrolled in graduate education in library and archival studies (Gallup Kopp 2019, 12; Hayden 2017, 134). Typically, such learning opportunities take place within the physical space of the special collections or archives; hands-on interactions with rare and archival materials, whether in reading rooms or at processing desks, are recognized as enriching educational experiences. Digital exhibitions extend collections access and support this educational role, providing librarians with opportunities to craft stories and create richly visual resources, with the potential to reach wider audiences. Jason Paul Michel and Marcus Ladd explain the value of digital exhibitions as an effective means of enhancing access:

Much of the materials kept in the library are documented in finding aids that may not be a natural source of information to undergraduate students or others who are unfamiliar with academic library systems. Using a narrative format, which students are more accustomed to experiencing, helps to bring down some of these barriers. (2015, 123)

While opportunities for digital engagement with archives and special collections are appreciated as a means for addressing access barriers for those who cannot visit the institution in person (Michel and Ladd 2015, 123; Sabharwal 2012, 8), they are often seen as weak echoes of in-person engagement (Gelfand 2013, 77). Furthermore, digital access cannot be equated with accessible access, as Kristina L. Southwell and Jacquelyn Slater acknowledge: “the increased digital presence of special collections has not, however, translated to uniform access for all users”; in fact, the “ever-increasing move to a digital world is making clear that accessibility in the digital realm is just as important as in the physical world” (Southwell and Slater 2012, 457, 458). Digital collections and exhibitions expand both the reach of cultural heritage institutions and the responsibility to ensure these resources do not remove barriers only to create others in their place.5

During the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, public health orders required special collections and archives all over the world to close their brick-and-mortar spaces, revealing the value of digital collections and exhibitions as an essential means of access. As digital engagement became the primary means of engagement, heritage professionals had to reimagine how to go about their work of preserving and providing access to rare and unique materials—and, in academic settings, how to go about their work of supporting student learning. The University of Victoria Libraries Special Collections and University Archives provide one example: the curation of a digital exhibition on Victorian scrapbooks that would come to be used as an OER in undergraduate humanities classrooms.

With the goal of highlighting Victorian scrapbooks, an underused yet significant area of UVic’s collection, Bassett developed a plan to create a digital exhibition as part of a remote internship.6 Archives-focused experiential learning opportunities for master of library and information studies (MLIS) and/or of archival studies (MAS) students such as Bassett typically complement graduate coursework by assigning students a processing project, where they arrange and describe an archival fonds or collection from the institution’s backlog (Gallup Kopp 2019, 12). While archival materials are often featured in exhibitions, exhibition curation is not a traditional archival task. In the mid-twentieth century, some archivists perceived the curation of exhibitions as “non-archival” and a “superfluous luxury” that detracted from traditional tasks such as the creation of finding aids (Gelfand 2013, 50). Nevertheless, exhibitions of archival materials began to gain recognition as effective tools for education and outreach; they grew in popularity throughout the century, and this growth was further spurred on by the Library of Congress’s creation of the first online exhibition in 1992 (Gelfand 2013, 50–66). Today, curation of exhibitions (both analog and digital) is still not a central task in the archival profession; rather, exhibitions are often either a side project for information professionals or created by students as part of their coursework (Crowe, Gilmor, and Macey 2019, 147; Davis et al. 2017, 482). Therefore, Bassett’s archives-focused work term was unusual both in that it was conducted remotely and in that its output—instead of being a stack of satisfyingly organized Hollinger boxes—was the digital exhibit “Yes, this is my album”: Victorian Collections of Scraps, Signatures, and Seaweed (2020).7

Many aspects of the exhibition’s creation made Bassett’s work term a unique experience. To select scrapbooks for inclusion, Bassett searched finding aids and sent lists of materials to Dean, after which Dean pulled the materials from the archives and took pictures to send to Bassett. While perhaps not the most efficient method of selecting materials, this process placed Bassett in the position of an archives user, trying to find materials without having access to the vault itself. The experience had unexpected benefits: after choosing a final set of scrapbooks to digitize for the exhibition, Bassett serendipitously stumbled upon descriptions for a collection of family-made scrapbooks that had been catalogued as books rather than described as archives. When Dean pulled them from the shelves, it was immediately evident that the Kidman family’s scrapbooks would be essential additions to the exhibition—and later, essential additions to the accompanying workshop designed by Bassett and Dean.8

The experience of curating the exhibition remotely also had significant implications for its design. Many digital exhibitions are designed as counterparts to physical exhibitions, often with the aim of encouraging users to visit the archives in person (Gelfand 2013, 73). In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the purpose of digital exhibitions necessarily shifted: now, digital exhibitions were designed as a primary means of engagement. Researching the materials from her home, Bassett aimed to support remote researchers’ engagement by embedding full versions of the digitized albums throughout the exhibition, along with contextual information and links to the material’s finding aids.9 While Bassett was aware that students could be a likely audience for “Yes, this is my album,” her exhibition design was not initially geared toward students, aside from the deliberate inclusion of archival terminology throughout the exhibition—an effort to support the development of primary source literacy.

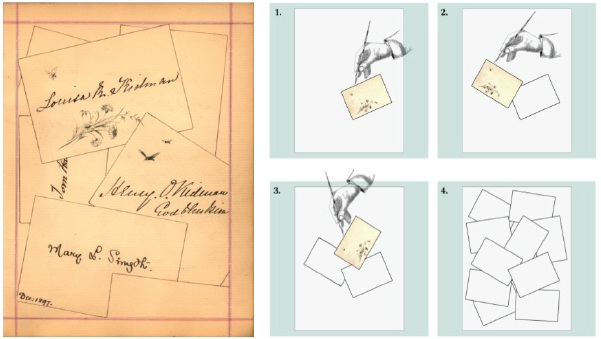

In its early stages, neither Bassett nor Dean envisioned the exhibition primarily as an educational tool. However, its potential for pedagogical use was highlighted by the librarians’ workshops in the Crafting Communities series. Drawing inspiration from the volumes in the exhibition, the archivists designed their workshop to provide a hands-on experience of activities related to Victorian autograph albums and scrapbooks (Figure 3). The workshop introduced the exhibition and related experiential learning opportunities to a broad audience, including faculty, students, cultural heritage colleagues, and community members. While held remotely, the workshop created community around a shared practice of experimentation with a Victorian pastime. Learning through doing (whether experimenting with a dip pen, creating homemade glue, or cutting and pasting scraps) invites creativity and reflection beyond reading about the Victorian period. The resources created for the workshop, including a materials handout, are available at the Crafting Communities website.

Figure 3: Left, page from the Ella Kidman autograph album (1897), held by UVic Libraries; right, workshop instruction graphics designed by Bassett and inspired by the Ella Kidman autograph album.

As noted above, scrapbooking, as a practice, invites creators to retain, revise, remix, reuse, and redistribute (the 5R activities central to open content [Wiley n.d.]), a process encouraged and enacted during the workshop. While it is not always obvious how digital exhibitions are being incorporated and used in teaching, in this case the close collaboration between the exhibition creator, her supervisor, and faculty resulted in the inclusion of the exhibition in syllabi and an invited guest lecture. This experience illustrates the value of interdisciplinary collaboration, the potential for libraries to author OERs, and the pedagogical power—and fun—of engaging learners in experiential activities. Demonstrating the potential of hands-on learning in an online environment, the constraints of the pandemic pushed archivists and instructors alike to be creative in opening access to, and engaging with, Victorian scrapbooks and autograph albums.

Although “Yes, this is my album” was initially conceptualized as a realizable project during the COVID-19 pandemic, the experience sheds light on both the value of library-faculty collaboration in the creation and promotion of exhibitions and the potential of digital exhibitions to function as OERs. The exhibition, along with its digital collection of Victorian scrapbooks, is open—that is, UVic Libraries assigned them the Creative Commons (CC) license Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0). With the exception of commercial purposes, this license permits anyone to engage in 5R activities central to open content, that is, retain, revise, remix, reuse, and redistribute (Wiley n.d.). While some in the open movement might criticize any restrictions on use—in this case, for commercial purposes—these collections arguably constitute open content, a direction many cultural heritage institutions are moving towards for their digital collections. Melissa Terras identifies a number of GLAM organizations whose digital collections are open (notably the Rijksmuseum, the British Library, and the Wellcome Library) and observes, “the Open Access movement is both dependent on and encouraging to the open licensing of digital primary historical material, which in turn offers up further opportunities for research in the arts, humanities, and cultural heritage” (2015, 734).

Open digital collections and exhibitions also provide opportunities to support the educational missions of libraries and archival institutions (Gelfand 2013, 51).10 They can extend the institution’s pedagogical role, implicitly in providing access to and interpreting cultural artifacts, and explicitly in encouraging educational extensions to exhibitions through class visits and/or the creation of supplementary open learning resources.11 While archivists and special collections librarians are increasingly working as educators to support student engagement with primary sources, Gueguen explains that “most suppose that students get this exposure in person, in the archives” (2010, 98). This experience provides further evidence to existing claims that archives-focused digital exhibitions have value as educational resources (Gelfand 2013, 76; Gueguen 2010, 99) and ultimately clarifies the value of treating digital exhibitions as OERs—as open educational resources with the potential to support in-depth learning opportunities, both in person and remotely.

Getting Scrappy in the Classroom

The “Yes, this is my album” online exhibition and Dean and Bassett’s scrapbooking workshop informed three versions of a hands-on scrapbooking assignment, each version adapted to the topics and objectives of Korda, Leighton, and Warne’s courses. With these assignments, the instructors created opportunities for experiential learning—despite the move to online learning—in order to foreground the embodied knowledge that comes from hands-on making (Jordi 2011, 187; Kolb 2015; Michelson 1998; Michelson 2015). The instructors took inspiration from Matt Ratto’s (2011) experiments with “critical making,” an approach that seeks to “connect two modes of engagement with the world that are often held separate—critical thinking, typically understood as conceptually based, and physical ‘making’” (253). Though Ratto’s experiments engage with more recent information technologies, this approach is well suited to explorations of nineteenth-century information technologies such as illustrated periodicals and scrapbooks. Using nineteenth-century methods of collage enabled our students—in Ratto’s words—”to make new connections between the lived space of the body and the conceptual space of scholarly knowledge” (2011, 254).

Leighton’s assignment, which we share in Appendix 1, was developed for an upper-level course on late Victorian fiction and required students to research a topic in digitized Victorian-era newspapers and magazines. Having identified a topic related to a literary text selected from the class reading list, students located relevant images and text to feature in their assignments and produced a collage page that creatively depicted their discoveries about their topic and its relationship to the literary text. The final step was to write an accompanying report that explained their research and creative processes, outlined their research findings, and articulated what the process of researching and scrapbooking taught them about Victorian print culture. Appendix 1 includes not only images of students’ scrapbook pages but also written excerpts from their longer reports.

The learning objectives for Leighton’s assignment were consistent with those for a research essay grounded in Victorian periodical press research. Students writing a research essay on hypnotism in Bram Stoker’s Dracula or valentines in Thomas Hardy’s Far from the Madding Crowd, for example, would be expected to undertake primary research in the Victorian periodical press as part of their research process. This research would normally be scaffolded through a series of in-person workshops in the UVic Libraries’ computer lab, where Leighton and a subject librarian would conduct a workshop geared toward increasing students’ primary source literacy, particularly using UVic’s Gale databases (from the Times Digital Archive, 1785–2014 and the Illustrated London News Historical Archive, 1842–2003 to the Nineteenth Century UK Periodicals and the British Library Newspapers databases). For this virtual scrapbooking assignment, students received similar support in developing information literacy through workshops conducted by Leighton in synchronous online classes. Through this assignment, students came to understand not only the Victorian periodical press but also Victorian fiction itself as forms of collage—of genres (realism, sensation, gothic, detective fiction, melodrama) or of characters’ voices or of print forms (as in Dracula, with newspaper clippings, phonograph recordings, diary entries, and medical journals, which inspired the collage below, in Figure 4).

Figure 4: Scrapbook page from Reed Eckert’s “Monstrosity in Bram Stoker’s Dracula.”

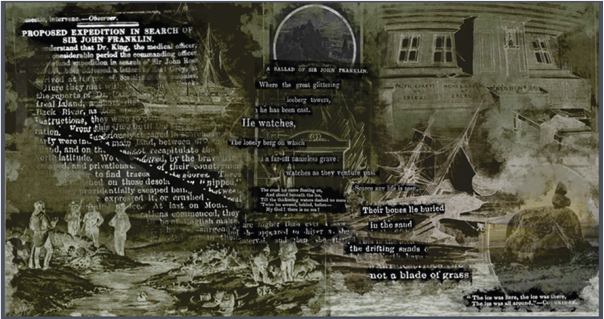

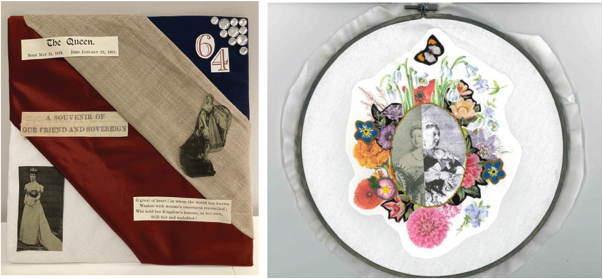

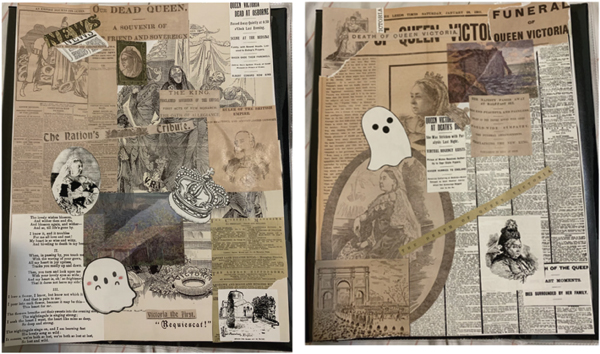

Appendix 2 shares Warne’s assignment, which was developed for a 2000-level course on poetry and grief. Like Leighton’s assignment, Warne’s required students to use both nineteenth-century periodical press materials and scrapbooking methods to address course content and readings. Warne’s course explored representative examples of elegiac poetry, including contemporary poet Anne Carson’s Nox, a book-length elegy that uses scrapbooking methods. Students were asked to explore periodical press coverage of one of two widely publicized deaths: the passing of Queen Victoria in 1901 and, decades earlier, the death of explorer Sir John Franklin in the Arctic. Through their research on digitized periodical reports on these events, students gained knowledge of the prevalence of memorial poetry in the nineteenth-century press as well as of defining literary characteristics of memorial poetry.

This was, for many students in Warne’s class, their first experience working with digitized newspapers and magazines. Instead of searching digitized periodical collections, Warne’s students worked with two repositories of pre-selected materials, each containing approximately forty digitized articles. Drawing on Bassett’s exhibition, students became familiar with the collection, curation, and design work involved in Victorian-era scrapbooking. Their exploration of this OER prepared students to create scrapbook pages but also to study Carson’s Nox, which is a facsimile of a memorial scrapbook that includes sketches, photographs, and both typed and handwritten passages. Working on their own scrapbooks while studying Carson’s experimental elegy significantly enriched students’ awareness of and interest in the materiality and messages of Carson’s project. Students submitted between one and three scrapbook pages and wrote a two-part reflection, the first part reflecting on what they learned about public grief and memorial poetry through their reading of periodical press coverage and the second part sharing a maker’s statement about their scrapbook pages. Appendix 4 includes images of students’ scrapbook pages.

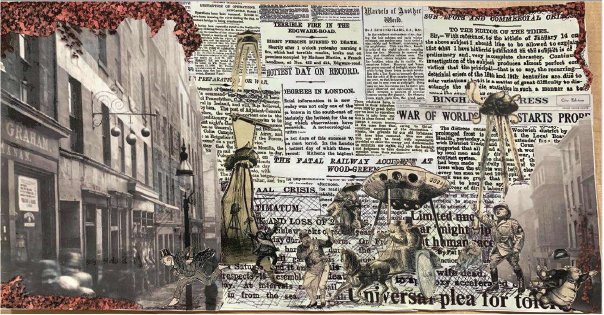

Korda’s assignment, shared in Appendix 3, shows how this assignment can be adapted to suit disciplines outside of literary studies—such as history and art history—by adjusting its emphasis. For an art history class that focuses on modern art, for example, the assignment is used as a means of reflecting on scrapbooking and collage as critical strategies. Modern art histories frequently trace the origins of collage to Pablo Picasso’s and Georges Braque’s experiments in the year 1912, but looking back at the nineteenth century and engaging with exhibitions like “Yes, this is my album” and the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art’s Cut and Paste: 400 Years of Collage (2019) demonstrates that collage has a longer history (Gowrley 2019, 25). Korda’s art history students engage with this history of collage and consider its relationship to the visual culture of modern life, which they explore further by browsing or searching digitized illustrated periodicals published between 1850 and 1914. Students can choose to focus on one particular topic or event reported in periodicals, or they can choose to focus on a single year or a single week of one publication. Using five to eight pages that they select for close looking and reading, students create scrapbook pages that respond to both their chosen historical materials and historical examples of scrapbooking and collage studied in class. In a written response, they reflect on what they have learned from the process about modern art, visual culture, and the relationship between them.

As our assignment sheets outline, in addition to drawing on the “Yes, this is my album” exhibition, our students benefit from the support of other resources: a short video demonstrating collage methods commissioned from artist and art educator Daniel Fountain, a podcast episode created by Cath Feely, and an interview Leighton conducted and recorded with Bassett to share with her class. In future iterations of this assignment, we will explore the value of more recently developed resources: interviews with Bassett, Freya Gowrley, and Alison Hedley on scrapbooking history for the Victorian Samplings podcast and Victorian Things, a digital exhibition that features descriptions and analyses of two Victorian scrapbooks as well as a scrap screen made by Charles Dickens and William Macready.

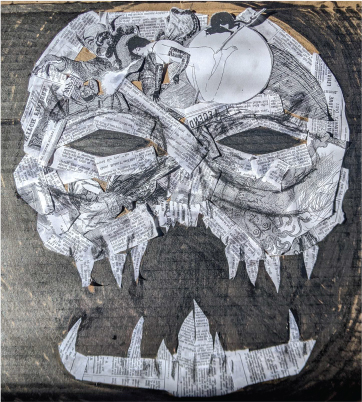

Figure 5: Digital scrapbook page by Keenan Hosfield on the death of Sir John Franklin.

Though these assignments privilege visual engagement and hands-on making, students with visual disabilities and students with limits on their manual dexterity can be offered adapted versions of this assignment and could be consulted on their preferences regarding the nature of those adaptations. Digital methods could be useful for students with dexterity limits; the option of creating a text-only collage or collage poem, based on phrases and passages excerpted from a selection of screen-reader-compatible digitized articles from the periodical press, is one option for accommodating students with visual disabilities. Students might be open to, and engaged by, a version of the assignment that prioritizes audio, with students employing accessible audio-editing software tools, like Audacity or Pro Tools, to record and edit an audio collage that combines recorded readings of passages, music, and captured sound or sound effects. We recommend that any adaptation of this assignment be offered as an option not only to students requiring accommodation but to all students in the class.

We also recommend asking students to share their work in a virtual exhibition, which can be held synchronously during class time, with students viewing class assignments as a group, or asynchronously on, for example, platforms available through course management systems. A virtual exhibition of class work emphasizes Ratto’s point that “critical making emphasizes the shared acts of making. . . . The final prototypes are not intended to be displayed and to speak for themselves. Instead, they are considered a means to an end, and achieve value through the act of shared construction, joint conversation, and reflection” (2011, 253). Whether this time for group conversation and reflection is held synchronously or asynchronously, each student should provide a brief written description of all scrapbook pages submitted as part of their assignment (shared verbally at the in-class exhibit or included as a recording if shared asynchronously). As Georgina Kleege and Scott Wallin (2015) argue in “Audio Description as a Pedagogical Tool,” audio description benefits all students: “Along with increasing awareness of disability, audio description pushes students to practice close reading of visual material, deepen their analysis, and engage in critical discussions around the methodology, standards and values, language, and role of interpretation in a variety of academic disciplines.”12

Figure 6: Scrapbook page by Victoria Giltrow on the death of Sir John Franklin.

One outcome of the virtual exhibition of assignments was its contribution to community building in the classroom. Students who had not been regular participants in class discussion found their voices in this exercise, feeling noticed and appreciated by their classmates and offering commentary on other students’ work at a time when offering commentary on course readings was something they were comparatively reluctant to do, perhaps out of a lack of confidence, perhaps due to a lack of motivation. Students were very engaged by this exercise, genuinely surprised by the very different projects that classmates produced despite working with the same body of periodical material and responding to the same instructions. Students were consistently generous in their responses to their peers’ work, offering not just the encouragement of praise but also very detailed comments. In their remarks, they highlighted distinguishing details; they recognized the same images and text from the periodical press being used in very different ways, thematically and stylistically. Part of the success of the assignment in terms of building a sense of community can be attributed to the space it created for students to share their interests outside of the classroom. Referencing a favorite TV series; sharing crafting or art-making interests, such as sewing or painting; expressing themselves creatively: these opportunities were welcomed by students at a time of limited social connection with members of the class.

Figures 7 and 8: Scrapbook projects on the death of Queen Victoria that pair printed digitized periodical content with fabric elements, by Kayla Cote (left) and Lucie Von Schilling (right).

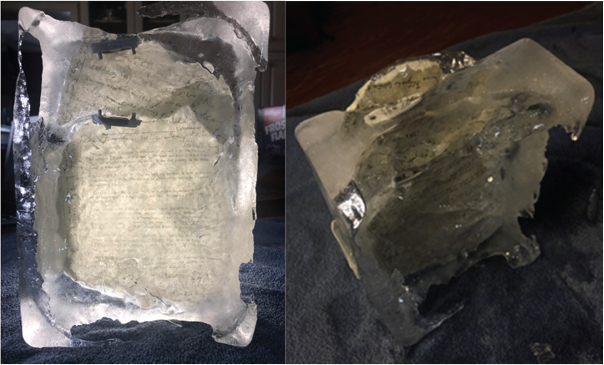

Asking students to examine and repurpose digitized nineteenth-century periodicals also contributes to developing primary source literacy skills, which is an objective of this assignment across all three classes. Searching, browsing, reading, and arranging nineteenth-century periodicals familiarizes students with the process of database research with digitized materials while also calling attention to their materiality. This may seem counterintuitive since we lose the materiality of these sources in the translation from the printed page to the digital image, but in the process of printing out, cutting, and pasting their digital sources, students enact a further remediation, one that calls attention to the visual and material format of the page—and the interaction between text and image (as in the collage in Figure 10, which also features hand-drawn cross-hatching that mimics nineteenth-century engraving techniques). Students must look closely at the various textual and illustrative elements of their sources to determine what they will poach for their assignments, and in the process of cutting and pasting they must engage with the physical material and shapes of these elements. Though they are working with twenty-first-century paper, their methods are rooted in nineteenth-century practices and therefore provide a prompt for reconsidering the material presence of periodicals in Victorian lives. Many of the completed assignments took on insistently material form, suggesting that students were able to conceptualize their sources as material objects. Some students used crumpled or yellowed paper as a base for their collages to simulate the look of aged paper, while others integrated additional materials such as textiles or reproductions of paintings that referenced the wider visual and material culture in which periodicals circulated. The most insistently material assignments—that is, those that called attention to the materiality of their source materials—were among the most memorable of the assignments and included one unique attempt to create a collage about Franklin’s lost expedition in ice by floating newspaper scraps in water and placing them in a freezer (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Scrapbook pages mounted in ice exploring the death of Sir John Franklin, by Tessa Thevenot.

Figure 10: Scrapbook page by Evie Ockelford for “‘The Martians are coming!’: Media, Crisis and The War of the Worlds.”

Some students chose to stay on screen and work digitally with their materials. For some, the choice was a practical one; students without easy access to a printer were able to make their scrapbook pages without locating a printer and paying for printing. For others, it was creative. These students responded, with success, to the onscreen nature of distanced learning exemplified by our visit to a virtual exhibition of digitized scrapbooks and our reading of digitized nineteenth-century periodicals onscreen, as well as to the wider context of twenty-first-century screen culture. Students who worked digitally were able to employ techniques like colorization and image fading; they were also able to crop, reverse, and resize images. One student combined digital and cut-and-paste techniques, digitally changing the colour tone of her press clippings to create a sepia effect associated with older photographs (Figure 10). While this use of digital methods distanced some students from the nineteenth-century hands-on practices that the assignment was designed to explore, their work still brought together nineteenth-century and twenty-first-century methods and materials in productive ways. For example, a collage about Queen Victoria’s death included ghosts sourced from a Google Images search floating across the page’s surface (Figure 11). One particularly cute ghost with pink cheeks references the popular Japanese kawaii aesthetic and brings to mind the kind of digital cutting-and-pasting that dominates today’s world.

Figure 11: Scrapbook pages by Ayesha Aamir exploring the death of Queen Victoria.

In some cases, techniques and imagery collide in ways that offer critical interventions into the narratives offered by Victorian periodicals. The kawaii ghost offers a suggestion for how these interventions can happen, since it calls attention to the wide-ranging aesthetic vocabulary of our students and to the various cultural influences that they bring to their study of Victorian culture.13 Our students’ varied experiences and backgrounds can result in re-interpretations of periodical pages that decentre the white, colonial, and patriarchal viewpoints of the nineteenth-century periodical press. For example, one collage created at our scrapbooking workshop (which can be seen on the Crafting Communities site’s Gallery page) responds critically to British imperialism by slicing up a union jack and layering the fragments over illustrations of birds so as to appear to imprison them on the page. Another collage (also posted on the Gallery page) merges women’s bodies with decorative objects to critique Victorian constructions of femininity. Other examples moved away from the scripts supplied by Victorian periodicals by combining Victorian scraps with colourful twenty-first-century imagery that brought people, places, and languages that would have been marginalized in the British Empire into the centre of the composition. This recentring happens visually and metaphorically within the space of the page and can serve as a prompt for further classroom discussion and reflection.

In reflecting on this assignment (in and beyond the assignment report), students in Leighton’s class commented on the challenge and reward of intensive research on the Victorian periodical press—as well as the surprising pleasure of making as a way of learning. When students were invited by Warne during a synchronous class to change their Zoom name to “Anon” and then to use the Zoom chat to share their experience of this assignment, the responses were very positive. Several students commented on how they found a change from essay writing beneficial and welcome; many students’ responses referenced enjoyment or fun. One student noted, “I loved writing poetry with words that used to be someone else’s;” another offered: “I liked how the assignment was unconventional, it really challenged me as a writer, to do something outside my comfort zone.” Students highlighted connections to course content; one student noted, “Honestly got me interested in poetry again;” another shared: “this assignment gave me the time to relax and enjoy what I was doing, but it also help[ed] me learn new information about historical figures that I never heard/knew of before.” One of the more detailed responses touches on several of these themes: “I found it really engaging and it was a nice break form [sic] more restrictive academic assignments. It was an assignment I actually enjoyed doing, and allowed for a lot of reflection on the reasons I made certain creative decisions. It was nice to have a first hand experience of a creative outlet when dealing with things associated with grief/mourning.” We find the following response especially noteworthy: “I really enjoyed having assignments that did not complete[ly] hinge on my writing ability but also my ability to understand and create other media” (Anonymous comments shared via Zoom chat during a synchronous meeting of English 2980, April 15, 2021).

Notably, students initially expressed skepticism about this assignment. Accustomed to writing academic essays, students wondered about the academic value or even the appropriateness of engaging creatively with digitized materials. Their perspectives changed over time, however. One student shared: “it felt odd as I was going to start and I had no clue what I was going to do. But once I started reviewing the documents[,] headlines were just popping at me to help illustrate a narrative of Queen Victoria. I enjoyed it the more as I went along.” As another student noted, “I was afraid to do this project upon reading the syllabus for this course, . . . but this project has in all honesty been one of the most personally fulfilling, profoundly interesting, and thought-provoking assignments I have ever done” (Anonymized student comment made on assignment submission to Leighton, April 12, 2021). Striking a similar note, another student observed, “At first I thought it was not very academic, but the videos and materials (such as pictures and news articles [. . .]) changed my mind” (Anonymous, comment in Zoom chat for synchronous meeting of Warne’s English 2980, April 15, 2021). Asked to comment anonymously on the assignment at the end of term, students championed the inclusion of assignments of this kind post-pandemic. A student offered the following reflection: “The unconventional projects seemed unnecessary at first, but I actually really enjoyed doing them! They did help me learn about Victorian culture in new and exciting ways. I hope that those more creative components of the class are kept when learning moves back to in person. I’ve never had this much fun doing a university project” (Anonymous, personal communication to Leighton, May 6, 2021).

Concluding Thoughts and Recommendations

As a case study, this assignment offers an example of what can happen when librarians and instructors collaborate. In our case, our collaboration was not limited to sharing materials in a unidirectional manner, with librarians creating resources that instructors used in their classrooms. It was, instead, the result of ongoing discussion about how to meaningfully engage students with the primary materials curated by librarians and archivists. By way of conclusion, we would like to offer a list of recommendations for instructors and for archivists and librarians based on what we have learned.

Recommendations for instructors:

- Aim for early and sustained engagement between instructors and collaborators, including librarians. Such engagement will help instructors and students move away from an instrumentalist or transactional view of librarians’ contributions and resist the perception of librarians and archivists as “support” for the research process rather than integral to it.

- Engage artists and art educators, offering appropriate financial compensation.

- Use open-access resources, such as digital exhibitions and podcasts.

- Produce a sample assignment to share with students, both the crafted piece and a writing sample, or use the work of a previous student with permission.

- Adapt the assignment for students with disabilities or students who lack access to materials and/or tools required for hands-on work.

- Integrate a capstone sharing event (e.g., a virtual gallery with a live component), inviting or re-engaging individuals who supported the event, including collaborating librarians and artists. Capstone events provide students opportunities to share with one another and reconnect with people who have supported their work, including librarians and artists.

Recommendations for archivists and librarians:

- Consider the value of digital exhibitions for research, education, and outreach.

- Seize advantage of opportunities offered by digital exhibitions and connected workshops, re-framed as educational resources, for outreach with both students and broader communities, in support of curricular and lifelong learning.

- See the creation of exhibitions as complementary to other archival tasks. Research for digital exhibitions can be meaningfully integrated into metadata production for both digital objects and finding aids.

- Highlight the roles of archivists and librarians as educators. For more information, consult the Canadian Association of Research Libraries, Competencies for Librarians in Canadian Research Libraries (2020).

- Seek out opportunities for collaboration with instructors by inviting feedback on digital collections and exhibitions and by engaging in conversation about how these resources might support research and learning.

Appendices

- Appendix 1: Leighton’s Assignment, Marking Rubric, and Student Examples: English 381: Late-Victorian and Edwardian Fiction, U of Victoria, Winter 2021

- Appendix 2: Warne’s Assignment and Sample Assignment: English 2980: Poetry of Mourning, U of Manitoba, Winter 2021

- Appendix 3: Korda’s Assignment: Augustana Faculty, Visual Art 220: Modern Life, Modern Art Scrapbooking Assignment, U of Alberta, Augustana Faculty

- Appendix 4: Work Shared by Warne’s Students from English 2980: Poetry of Mourning, U of Manitoba, Winter 2021

Acknowledgements

Thank you to KULA co-editor Samantha MacFarlane and our two anonymous readers for their helpful feedback on earlier versions of this article. Thank you to students at the Universities of Manitoba and Victoria for sharing their work. Thank you also to Anne Mirejovsky at the University of Alberta for piloting Korda’s assignment and to those who participated in the Crafting Communities Scrapbooking Workshop, led by Dean and Bassett. Thank you to Dr. Cath Feely and Dr. Freya Gowrley for the knowledge and inspiration they shared during their Being Human Scrapbooking event in fall 2020. Thank you to University of Victoria teaching assistant Michael Carelse for his contribution to the development of Leighton’s rubric. Thank you to Allegra Stevenson-Kaplan and Robert Steele for assistance in preparing this article for publication. Thank you lastly to artist and art educator Dr. Daniel Fountain for the creativity and expertise he shared in the demonstration video he created for our students’ use and to Warne’s and Leighton’s university departments for funding the video. We also want to acknowledge UVic Libraries and the Young Canada Works in Heritage Institutions program, implemented by the Government of Canada’s Department of Canadian Heritage, which provided funding for Bassett’s positions at the University of Victoria Libraries Special Collections and University Archives. For funding the Crafting Communities series, we are grateful to the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the Victorian Studies Association of Western Canada, and the Universities of Victoria, Manitoba, and Alberta.

References

Alexander, Kara Poe. 2013. “Material Affordances: The Potential of Scrapbooks in the Composition Classroom.” Composition Forum 27 (2013). https://compositionforum.com/issue/27/material-affordances.php. Archived at: https://perma.cc/AXG3-CQCK.

Association of College and Research Libraries. 2006. “ACRL-RBMS/SAA Guidelines on Access to Research Materials in Archives and Special Collections Libraries.” http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/jointstatement. Archived at: https://perma.cc/7JUL-FFT6.

Association of College and Research Libraries. 2020. “ACRL Code of Ethics for Special Collections Librarians.” https://rbms.info/standards/code_of_ethics/. Archived at: https://perma.cc/H6UM-R84C.

Bassett, Elizabeth. 2021. Kidman family fonds [finding aid]. Victoria, BC: University of Victoria Libraries Special Collections and University Archives. https://uvic2.coppul.archivematica.org/kidman-family-fonds.

Bassett, Elizabeth. 2020. “Yes, this is my album”: Victorian Collections of Scraps, Signatures, and Seaweed. University of Victoria Special Collections and University Archives. https://exhibits.library.uvic.ca/spotlight/scrapbooks.

Bassett, Elizabeth, Heather Dean, and Ruth Ormiston. 2021. “Victorian Scrapbooking.” Crafting Communities. https://www.craftingcommunities.net/victorian-scrapbooking.

Crowe, Katherine, Robert Gilmor, and Rebecca Macey. 2019. “Writing, Archives and Exhibits: Piloting Partnerships Between Special Collections and Writing Classes.” Alexandria: The Journal of National and International Library and Information Issues 29 (1–2): 145–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0955749019877084.

Davidson, Cathy. 2020. “The Single Most Essential Requirement in Designing a Fall Online Course.” HASTAC (blog). May 11, 2020. https://www.hastac.org/blogs/cathy-davidson/2020/05/11/single-most-essential-requirement-designing-fall-online-course. Archived at: https://perma.cc/HL68-N85S.

Davis, Ann Marie, Jessica McCullough, Ben Panciera, and Rebecca Parmer. 2017. “Faculty–Library Collaborations in Digital History: A Case Study of the Travel Journal of Cornelius B. Gold.” College & Undergraduate Libraries 24 (2–4): 482–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2017.1325347.

DeLong, Kathleen, et al. 2020. Competencies for Librarians in Canadian Research Libraries. Canadian Association of Research Libraries. https://www.carl-abrc.ca/strengthening-capacity/human-resource-management/core-competencies-21st-century-carl-librarians/. Archived at: https://perma.cc/7DN9-JEDE.

Erickson, Jesse. 2021. “Scrapbooks as Literary Documents.” SHARP News (blog), January 25, 2021. https://www.sharpweb.org/sharpnews/2021/01/25/scrapbooks-as-literary-documents/. Archived at: https://perma.cc/BCG4-LAPD.

Fountain, Daniel. 2021. Daniel Fountain. https://www.danielfountain.com/.

Friedlander, Linda. 2021. “Crucibles of Healing: The Enhancing Observational Skills Program at the Yale Schools of Medicine and Nursing.” In Artful Encounters: Sites of Visual Inquiry, edited by Christina Smylitopoulos, 81–123. Guelph, ON: Bachinski/Chu Print Study Collection, University of Guelph. https://atrium.lib.uoguelph.ca/xmlui/handle/10214/23773.

Gallup Kopp, Maggie. 2019. “Internships in Special Collections: Experiential Pedagogy, Intentional Design, and High-Impact Practice.” RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Cultural Heritage 20 (1): 12–27. https://doi.org/10.5860/rbm.20.1.12.

Garvey, Ellen Gruber. 2012. Writing with Scissors: American Scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance. New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195390346.001.0001.

Gelfand, Aleksandr. 2013. “If We Build It (and Promote It) They Will Come: History of Analog and Digital Exhibits in Archival Repositories.” Journal of Archival Organization 11 (1–2): 49–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332748.2013.882160.

Gowrley, Freya. 2019. “Collage Before Modernism.” In Cut and Paste: 400 Years of Collage, edited by Patrick Elliott, 25–33. Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland.

Gueguen, Gretchen. 2010. “Digitized Special Collections and Multiple User Groups.” Journal of Archival Organization 8 (2): 96–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332748.2010.513324.

Hayden, Wendy. 2017. “And Gladly Teach: The Archival Turn’s Pedagogical Turn.” College English 80 (2): 133–58. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44805961.

Institute for the Study of Knowledge Management in Education. OER Commons. Last modified 2021. https://www.oercommons.org/.

Jordi, Richard. 2010. “Reframing the Concept of Reflection: Consciousness, Experiential Learning, and Reflective Practices.” Adult Education Quarterly 61 (2): 181–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741713610380439

Kidman, Ella. 1897. Ella Kidman autograph album. SC624. Kidman family fonds. Special Collections and University Archives, University of Victoria Libraries. https://vault.library.uvic.ca/concern/generic_works/4b95b147-6a2d-4d0c-9392-9f3d585f1d6a.

Kleege, Georgina, and Scott Wallin. 2015. “Audio Description as a Pedagogical Tool.” Disability Studies Quarterly 35 (2). http://dx.doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v35i2.4622.

Kolb, David A. 2015. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education. O’Reilly Media.

Korda, Andrea. Forthcoming. “Experiential Learning in the Victorian Classroom: What Can We Learn from the Object Lesson?” In Victorian Culture and Experiential Learning, edited by Kevin A. Morrison. London: Palgrave.

Kuk, Hye-Su, and John D. Holst. 2018. “A Dissection of Experiential Learning Theory: Alternative Approaches to Reflection.” Adult Learning 29 (4): 150–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/1045159518779138.

MacFarlane, Samantha. 2018. Volatile Attractions: Saul Holiff, Johnny Cash, and Managing a Music Legend. University of Victoria Special Collections and University Archives. https://exhibits.library.uvic.ca/spotlight/holiff.

Mecklenburg-Faenger, Amy. 2012. “Trifles, Abominations, and Literary Gossip: Gendered Rhetoric and Nineteenth-Century Scrapbooks.” Genders 55 (Spring). https://www.colorado.edu/gendersarchive1998-2013/2012/02/01/trifles-abominations-and-literary-gossip-gendered-rhetoric-and-nineteenth-century. Archived at: https://perma.cc/BM6P-BDY5.

Michel, Jason Paul, and Marcus Ladd. 2015. “‘Snow Fall’-ing Special Collections and Archives.” Journal of Web Librarianship 9 (2–3): 121–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2015.1044689.

Michelson, Elana. 1998. “Re-membering: The Return of the Body to Experiential Learning.” Studies in Continuing Education 20 (2): 217–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037980200208.

Michelson, Elana. 2015. Gender, Experience, and Knowledge in Adult Learning: Alisoun’s Daughters. London: Routledge.

Ontario Council of University Libraries. 2017. White Paper on Open Educational Resources. https://ocul.on.ca/node/6820. Archived at: https://perma.cc/V6WT-GE3T.

Open Art Histories. 2021. “Watch, Look, and Listen.” https://openarthistories.ca/watch-look-listen.

Pasupathi, Vimala. 2014. “The Commonplace Book Assignment.” The Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy, March 11, 2014. https://jitp.commons.gc.cuny.edu/the-commonplace-book-assignment/. Archived at: https://perma.cc/4KJ4-QL8C.

Ratto, Matt. 2011. “Critical Making: Conceptual and Material Studies in Technology and Social Life.” The Information Society: An International Journal 27 (4): 252–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2011.583819.

SAA-ACRL/RBMS Joint Task Force on the Development of Guidelines for Primary Source Literacy. 2018. “Guidelines for Primary Source Literacy.” https://www2.archivists.org/sites/all/files/GuidelinesForPrimarySourceLiteracy-June2018.pdf. Archived: https://perma.cc/AXB3-23C9.

Sabharwal, Arjun. 2012. “Digital Representation of Disability History: Developing a Virtual Exhibition.” Archival Issues 34 (1): 7–26. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41756159.

Seaman, Jayson, and Alison Rheingold. 2013. “Circle Talks as Situated Experiential Learning: Context, Identity, and Knowledgeability in ‘Learning from Reflection.’” Journal of Experiential Education 36 (2): 155–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053825913487887.

Skidmore, James. 2020. “My Approach to Teaching Online.” Skid. https://www.jamesmskidmore.com/teaching-online. Archived at: https://perma.cc/PR7W-PEBH.

Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. 2019. “Guidelines for Effective Knowledge Mobilization.” Last modified June 17, 2019. https://www.sshrc-crsh.gc.ca/funding-financement/policies-politiques/knowledge_mobilisation-mobilisation_des_connaissances-eng.aspx. Archived at: https://perma.cc/RN9Y-MPTK.

Southwell, Kristina L., and Jacquelyn Slater. 2012. “Accessibility of Digital Special Collections Using Screen Readers.” Library Hi Tech 30 (3): 457–71. https://doi.org/10.1108/07378831211266609.

Stommel, Jesse. 2020. “How to Build an Online Learning Community: 6 Theses.” May 19, 2020. https://www.jessestommel.com/how-to-build-an-online-learning-community-6-theses. Archived at: https://perma.cc/FJL2-3ZA6.

Terras, Melissa. 2015. “Opening Access to Collections: The Making and Using of Open Digitised Cultural Content.” Online Information Review 39 (5): 733–52. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-06-2015-0193.

Tiessen, Rebecca. 2018. “Improving Student Reflection in Experiential Learning Reports in Post-Secondary Institutions.” Journal of Education and Learning 7 (3): 1–10. http://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v7n3p1.

UNESCO. 2019. “Recommendation on Open Educational Resources (OER).” http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=49556&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html. Archived at: https://perma.cc/22RH-U7ZW.

University of Victoria Libraries. n.d. “Strategic Directions.” Accessed June 15, 2021. https://www.uvic.ca/library/about/ul/strategic/index.php. Archived at: https://perma.cc/J48T-72X8.

University of Victoria Special Collections and University Archives. 2017. Victoria to Vimy: The First World War Collections at the University of Victoria Libraries. https://exhibits.library.uvic.ca/spotlight/wwi.

Victorian Things. 2020–. University of Victoria Libraries. https://omekas.library.uvic.ca/s/crafting/page/about.

Walz, Anita, Kristi Jensen, and Joseph A. Salem, Jr. 2016. Affordable Course Content and Open Educational Resources. SPEC Kit 351. Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries. https://doi.org/10.29242/spec.351.

Warne, Vanessa, et al., hosts. Victorian Samplings. Crafting Communities, 2020–. https://www.craftingcommunities.net/victorian-samplings.

West Virginia University Press. 2020. “Pedagogies of Care: Open Resources for Student-Centered & Adaptive Strategies in the New Higher-Ed Landscape.” 2020. https://sabresmonkey.wixsite.com/pedagogiesofcare. Archived at: https://perma.cc/8QNH-V84Z.

Wiley, David. n.d. “Defining the ‘Open’ in Open Content and Open Educational Resources.” Accessed June 15, 2021. http://opencontent.org/definition/. Archived at: https://perma.cc/M5Q6-2G84.

Footnotes

1 For more examples of assignments that incorporate scrapbooking and commonplacing practices, see Alexander (2013), Erickson (2021), and Pasupathi (2014).

2 All assignment excerpts are reproduced with students’ permission. The authors also confirmed with their respective institutions that ethics approval was not required for including anonymous student feedback in this paper.

3 Open Art Histories (2021), a platform for visual art and museum studies instructors in Canada, also includes museum image collections and archives in their collection of resources.

4 For more on primary source literacy, see the “Guidelines for Primary Source Literacy” (SAA-ACRL/RBMS Joint Task Force on the Development of Guidelines for Primary Source Literacy 2018).

5 Archivists and librarians are increasingly making explicit the importance of providing equitable access to all patrons, regardless of ability, as can be found in, for example, the “ACRL-RBMS/SAA Guidelines on Access to Research Materials in Archives and Special Collections Libraries” (2006).

6 In May 2020, while nearing the end of her graduate program in library and archival studies at the University of British Columbia, Bassett was hired for a student co-op position at UVic Special Collections and University Archives. Responding to pandemic circumstances, Dean (Associate Director, UVic Special Collections) worked with Lara Wilson (Director of UVic Special Collections and University Archivist) to imagine a remote internship. Bassett’s remote curation of the exhibition was supported by the collaboration of several departments at the University of Victoria Libraries: Special Collections and University Archives, the Digitization Centre, the Digital Scholarship Commons, and Metadata. Full acknowledgments: https://exhibits.library.uvic.ca/spotlight/scrapbooks/about/about-the-exhibit.

7 Because UVic Libraries already had a number of successful digital exhibitions, including Victoria to Vimy (2017) and Volatile Attractions: Saul Holiff, Johnny Cash, and Managing a Music Legend (2018), Bassett’s project benefited from the established workflows and procedures already in place to support digital exhibitions.

8 After incorporating two of the three Kidman family scrapbooks into the exhibition, Bassett created a new finding aid for the materials (Bassett 2021). This experience provides evidence for the argument, made by some archivists, that exhibition creation enriches description practices (Gelfand 2013, 56).

9 An additional researcher-focused feature is the “Browse” section of the exhibition, which gives users the opportunity to view the digitized scrapbooks without the contextualizing narrative (i.e., as a digital collection instead of a digital exhibition). To ensure that researchers would be able to connect the materials back to their archival contexts, Bassett provided detailed metadata for each item, including, for example, fields for fonds/collection title, fonds/collection creator, accession number, and finding aid URL. Bassett also designed the “Browse” page so that viewers could view the items organized by the archival fonds/collections they are located within. These design features are supported by Gueguen, who asserts that researchers prefer digitized collections over digital exhibitions, particularly if they are designed to “match as closely as possible the traditional organization in the archives” (2010, 99).

10 In its Strategic Directions, UVic Libraries (n.d.) makes explicit its educational role to “advocate for and enable learning and research innovation through open, globally networked knowledge mobilization” and “provide experiential learning opportunities for students and the broader community.” Like peer institutions, UVic Libraries offers workshops, classes, exhibitions, and events, which provide curricular, co-curricular, and lifelong learning opportunities for the campus and local communities. In addition, UVic Libraries publishes a number of open-access volumes, including KULA and a publishing imprint highlighting rare and unique materials from the Special Collections and University Archives. As a connector between the campus and the community, UVic Libraries facilitates knowledge mobilization—that is, the “wide range of activities relating to the production and use of research results, including knowledge synthesis, dissemination, transfer, exchange, and co-creation or co-production by researchers and knowledge users” (Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council 2019).

11 For example, the digital exhibition Victoria to Vimy includes a Grade 9 Social Studies Unit for general use, developed by UVic Education, Children’s Literature, and Indigenous Studies Librarian Pia Russell.

12 For examples of how visual description has been integrated into medicine and nursing programs, see Friedlander (2021).

13 For a discussion of how students’ situated knowledge (based on their identities, locations, and social relations) can inform experiential learning, see Tiessen (2018), Seaman and Rheingold (2013), Kuk and Holst (2018), and Korda (forthcoming).