CONVERSATION

Talking with My Daughter About Archives: Métis Researchers and Genealogy

Jessie Loyer (Cree-Métis)

Library, Mount Royal University

Darrell Loyer (Métis)

In a kitchen table discussion, a Métis genealogist and his Cree-Métis librarian daughter talk about the ways Indigenous people navigate archives, oral history, and research; discuss the inaccuracies that exist in records relating to Indigenous people; and consider the ways that records can supplement oral history about Métis culture.

Keywords: Indigenous archives; genealogy research; Métis; oral history

How to cite this article: Loyer, Jessie et al. 2021. Talking with My Daughter About Archives: Métis Researchers and Genealogy. KULA: Knowledge Creation, Dissemination, and Preservation Studies 5(1). https://doi.org/10.18357/kula.140

Submitted: 6 July 2020 Accepted: 30 October 2020 Published: 22 June 2021

Copyright: @ 2021 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Introduction

This is a conversation about archives and genealogy from us, an Indigenous dad and his daughter. Darrell Loyer is a Métis genealogist who often visits archives, libraries, and museums to do his research, and Jessie Loyer is a Cree-Métis librarian. We discussed the experience of going to the archives, the role that genealogy plays in Métis cultural transmission, and the challenges of encountering inaccuracies in the record. Despite these challenges, records can provide clarification and connect us with the stories of our families. There are three parts to this conversation: the first highlights Darrell’s experience as an Indigenous researcher navigating archives and oral histories, the second discusses inaccuracies in the record, and the third considers the future of this kind of genealogy research.

Methodology

Métis kitchen table talks1 cover a lot; they do not stay on one topic, but meander around and loop back around. People laugh a lot! This methodology does not set up an unequal power dynamic between an interviewer and their subject, but, rather, allows everyone’s voice to be heard. Métis kitchen table talks show the way that conversation while eating, drinking, and creating is a distinct form of knowledge transmission (Mattes and Racette 2019). Even though we have written this article together, we want to note that it does not feel entirely comfortable to be sharing oral histories this way. Something intangible is lost when stories are written down: you can’t see body language or expressions, but we tried to capture some of that in the transcriptions. Originally, we had planned to sit around the kitchen table and have several conversations on this topic, but COVID-19 happened, which prevented us from meeting the way we usually would over a meal. The audio from our conversation has all kinds of other background noise since we had to physically distance outside in Calahoo, Alberta, at our family home, so in the clips you will hear birds, vehicles, squeaking chairs, and a persistent cat. To limit contact, we recorded this single conversation on May 27, 2020, and all audio clips are provided by the authors.

Part 1: Doing Genealogy Research When You Are Indigenous

Being Indigenous in the Archives

On October 25, 2019, the Provincial Archives of Alberta (PAA) included on their Facebook page a profile of Darrell as a researcher using their records (PAA 2019). They were profiling users of the archives, and since Darrell retired, his genealogy research has incorporated more trips to archives, including the PAA. Darrell described the way that archival records could supplement oral history, and this positioning made Jessie, as a librarian, curious about Darrell’s experiences accessing archives: he had gone to the PAA specifically because he had heard that they had records related to genealogy. While archivists frequently write about user experience, it is rare to hear the first-hand experiences of Indigenous community members using the archives.

As in most archives, actually viewing the records requires assistance from a staff member, which may not be immediately clear to visitors. Darrell talks about how, similar to other archives, staff needed to help him on his first visit to the PAA:

DARRELL. I didn’t know what to do. But they were good. I just walked in—oh, you have to sign in, get your name and card and everything. And then you go in. And I knew nothing. And so they told me, they asked me what I wanted, and I said “genealogy,” and so then they took me over to the computer and then they sort of . . . she was very good, I can’t remember her name. And she walked me through. And then there’s a whole process; it’s kind of weird. You have to find what you’re looking for, but you can’t see it. You write it on the card, you go put it in a place, and you sit and wait. Then they go get it and they bring it back. Then you look at it.

JESSIE. And then did you make a copy or anything?

DARRELL. I made—they make copies of what you want after.

JESSIE. So, you basically can’t do anything yourself.

DARRELL. Just look. You have to request.

As in most cultural memory institutions, welcoming policies are only as good as the staff providing customer service. Staff in archives are largely non-Indigenous (Israel and Eyre 2017), and this can change the way that Indigenous researchers are welcomed into these spaces. In this case, one staff member limited the number of records Darrell could access.

DARRELL. But the next time I went, I had more records. And some woman was trying to be a little bit difficult.

JESSIE. [laughs] Like what did she try to do?

DARRELL. She tried to make me fill out more forms and then she was going to print them off and then I was going to have to come back.

JESSIE. And not get anything that time?

DARRELL. Yeah, ’cause there was too many; it was a limit or something. So, I just waited around and then a young person was coming. And then I said, “Well, how about if I”—you can only get, I think, ten at a time. I thought, “I’ll get ten and then I’ll leave and then I’ll come back and get the other ten!” And so, the young person just did it.

JESSIE. Just like, “This makes no sense.”

DARRELL. Yeah. But that person wanted to leave anyway. It was the end of their shift.

The process of accessing records, even for an experienced genealogist, is not easy. Learning to navigate different systems in different institutions and the policies that vary by institution can take as much time as understanding the records requested. Darrell showed Jessie the records request form.

DARRELL. Here’s what I had to order. See, they made me order and then . . .

JESSIE. What is this for?

DARRELL. For archives, for death records, birth records, marriage records of different people. And so then, the woman wanted me to write all this stuff down, so I had to write it all down, and the number, and the file number—you have to write all this stuff down. There’s a whole process. It’s kind of . . . you have to learn the process. It’s lots of work to find stuff.

JESSIE. It is.

DARRELL. Because it’s not just there. You have to dig.

The records that have been most helpful for Darrell are documents from marriages, births, baptisms, deaths, and censuses: these tend to focus on the ways that people are connected to each other, similar to the way that Métis genealogy is passed on orally. To research in these spaces, Darrell had to learn the terminology used in archival material, including words with specific meanings historically (such as spinster, which simply refers to an unmarried woman) or historical words for medical conditions. Researching is hard work, from navigating the structures of the archive and dealing with staff to travelling far distances to visit. But there is something about it that captivates Darrell; he will stay for hours to make the most out of the trip:

DARRELL. OK, Mom has just been talking about . . . I just want to go, go, go, go! I have a problem when I go to archives.

JESSIE. What’s the problem?

DARRELL. My problem is, I go there, and I just go, go, and keep doing, and keep working, and keep working. I don’t eat.

JESSIE. You don’t eat?

DARRELL. Maybe go the bathroom. I run to the bathroom. I come back. And I go, go, go, go.

JESSIE. Why?

DARRELL. ’Cause I just can’t leave. It’s an addiction, cha. No, it’s not! It’s just so interesting, and it just grabs me. And I can’t leave. I don’t eat.

JESSIE. Oh, God.

It Is Kept in Their Heads

Darrell’s experiences highlight the ways that archival records work best when they supplement oral history about how people are related. Darrell was raised by his Métis grandmother, Clara Loyer, née Cunningham, whom we call Nanny (Figure 1). She was a maskihkîyiskwêw and a midwife. She taught Darrell that it is important to know your relatives to understand your responsibilities. Even before he had a word for it, Darrell was doing genealogy with her.

Figure 1: Photograph of Nanny, Darrell’s Métis grandmother, who was named Clara Loyer (née Cunningham). Photo courtesy of Darrell Loyer.

JESSIE. Nanny would just tell you stories about people that were there or were coming to visit or just whatever?

DARRELL. Just, who people were related to, and how so-and-so was related. And everybody didn’t have this business about you were either—you knew your aunts and uncles and close family ties and then people who were related were your cousins. And so it was never really . . . sometimes they told how you were related, but it was also a very small group of folks, actually, because they all married each other. It was very close. And so, you knew if somebody was marrying somebody, you knew their family already. You knew. And so, in our family, we’ve got brothers marrying sisters. And so, the families were very close.

JESSIE. Yeah, ’cause Nanny’s sister married her . . .

DARRELL. Nanny’s sister married her husband’s brother. And then her niece married another brother.

JESSIE. Right.

DARRELL. [laughs]

JESSIE. Good family.

DARRELL. Yeah.

JESSIE. It makes sense, though. You would see people.

DARRELL. You’d see people, and so that . . . but even going back, people you would see, and you would always wonder then how they were related. And so, you would figure out. And she would tell you. It would be oral. You’d sit around. Because it wasn’t technology. People would visit, and talk, and you’d say, “OK, how about that person?” And sometimes you’d ask after. And sometimes you wouldn’t know. I didn’t find out ’til years later about some people, how they are related, like their great-great-grandparents was a Loyer, and so then they’re still connected. And like, I’d see Irene2 in St. Albert and she’d tell her kids, “This is your cousin,” and everybody: “OK.”

JESSIE. She just knew, but not necessarily how?

DARRELL. She knew. Not necessarily how. They probably knew how.

JESSIE. She knew how.

DARRELL. She knew how, but I didn’t yet. And so then, later on, doing genealogy, you figured out how, and yeah we’re cousins. So then you just have that in your head, and then that’s OK.

The role that family stories play in Métis cultural transmission is central, but Jessie asked Darrell where he first heard the term genealogy during his work.

DARRELL. Genealogy? I’ve been doing it since I was a kid. It was just in my head before.

JESSIE. Do you remember knowing it when other people didn’t? Like other people your age?

DARRELL. I don’t know. I know now I have relatives that will phone me and [laughs] somebody will ask, “How are we related to so-and-so?” Like Boo (Gloria) texted me the other day, “How are we related to somebody else?” and so it was easy. I just went, “Blah blah blah blah, this is how we’re related.” And she goes, she comes back: “It’s good to have a genealogist in the family.” But I don’t consider myself a genealogist. I just happen to know.

JESSIE. Do you remember when you ever heard that word for the first time?

DARRELL. What? Genealogist?

JESSIE. Yeah

DARRELL. I don’t. I remember doing stuff on paper. Oh, maybe when I was at the university. I started doing some—for a paper I did some kind of “how we’re all connected” back in the day. And then I found out that some of it was genealogy. The word.

JESSIE. Oh, the word. Would you just call it family stories, or relatives?

DARRELL. Just relatives.

JESSIE. Just whatever.

DARRELL. ’Cause we’re all connected. So yeah, no, I didn’t know that word.

One of the reasons that knowing genealogy is so important is that it tells Métis people about their responsibilities to the community.

DARRELL. So, you want to know why I do genealogy? No?

JESSIE. Yeah. I mean, that’s part of it.

DARRELL. Because I’ve always been doing genealogy. Nanny did it. In her head. It was all in your head. Because you had to know who you’re related to, and who your relatives were related to.

JESSIE. How come? Why would you need to know?

DARRELL. Because you have a responsibility to those people. They have a responsibility to you.

JESSIE. They’re your people.

DARRELL. Yep. And back then it was all in your head.

As Darrell got more interested in doing genealogy, he sought out other experts. He met Charles Denney, whose documents are now at the Glenbow Museum.

DARRELL. Charles Denney, I met him. I knew him. Back in the day.

JESSIE. What did he have?

DARRELL. He has—oh my God, Jessie—he had one of his bedrooms in his little apartment, because I went to his apartment. I don’t know if his wife was alive. I can’t remember if there was a woman there or not. Anyway, I went to visit him, because I was doing . . . I wanted to do genealogy more. Maybe I was going to university, because I was in town. And so, he has—oh, he had one bedroom that was just packed. Packed! With bookshelves, boxes, paper. All the genealogy on paper. But he had done phenomenal stuff.

JESSIE. Who was he?

DARRELL. Charles Denney. Just a genealogist person. And his wife was Métis.

JESSIE. Oh, so that’s how he knew.

DARRELL. That’s how he started, I think. Doing some of her family’s. And then it just went from family to the next family, to the next family and then all of a sudden it went to all of us out here. Because I think she is originally from maybe Manitoba.

JESSIE. Oh, so she’s not even Métis from here?

DARRELL. I don’t think so. But of course people are connected. Because lots of them got their wives from over there, way back. But he did phenomenal genealogy, lots, lots.

JESSIE. So, his stuff is now at the Glenbow.

DARRELL. Was! I think so. I think all that paper went to Glenbow.

JESSIE. That whole room! [laughs]

DARRELL. That whole room. It’s like, you can see it online, but it just says what he’s got, but you can’t . . .

JESSIE. It’s just a list.

DARRELL. A list. They’ve digitized, and you can click on it and look, but none of my stuff, our stuff. Like other families, maybe. I don’t know how they pick what goes on.

JESSIE. It’s mostly like interest, right? If they think that it’s something that more people will be interested in, then they might digitize it.

DARRELL. Because there’s lots. Lots.

JESSIE. And that’s the thing, right, how would you choose what of his many, many boxes of stuff to digitize.

DARRELL. But they did. They’ve done.

JESSIE. But maybe somebody requested it and they digitized it and then they put it up.

DARRELL. So, you said that his stuff at Glenbow is at U of A?

JESSIE. At the U of C.

DARRELL. Oh, U of C! Oh yeah. ’Cause it’s in Calgary.

JESSIE. So, the U of C took over a lot of the Glenbow’s archives, so now they have it there.

DARRELL. Oh, that doesn’t help me; it’s too far.

Part 2: Inaccuracies in the Record

Written Down by White People

Most records in archives about Indigenous people have not been created by Indigenous people. Indigenous genealogists have to note the ways that primarily white people in positions of power (like Indian agents, census-takers, and hospital staff) recorded official documents by mishearing or misidentifying Indigenous life.

DARRELL. And once it’s printed, that’s the hard part. Once it is printed in somebody’s genealogy or printed in a book or printed somewhere, then everybody thinks it’s true. So, you’ve got to watch, you got to be careful.

JESSIE. What else have you come across that is not right, or not quite right?

DARRELL. Oh, on the census records. [laughs]

JESSIE. [laughs] You were telling me last night!

DARRELL. People like spell—they hear, their own ear hears what the person said.

JESSIE. Livershawn!

DARRELL. Well yeah, no, but they hear . . . and so they think they’ve heard some name and they try and write it down in their own—because they’re not like Métis or Cree or whatever, and they . . . yeah.

JESSIE. They just hear the name wrong.

DARRELL. They hear the name wrong, and they write it in and there it is. And then it’s there forever.

The prejudices of those creating records are very clear to Indigenous researchers; it’s noticeable in records relating to our own family.

DARRELL. I haven’t showed this to Auntie Flossie and Auntie Marlene yet. It’s bad. It’s kind of prejudiced. Because, OK, it says the father is “Lloyd James Poitras,” “Mary Valerie Dion,” etc. The cause of death. It says, “Medical certificate of death,” and we got this Lavina. So she’s sixty-nine days old. The first one is “Bronchial pneumonia, 10 days,” “Candida albicans infection, 1 month.” Mom and I checked that out, whatever. She had, like, thrush, and she couldn’t suck. Another condition, contributing to death: “Malnutrition.”

JESSIE. Oh.

DARRELL. “Due to insufficient lactation of mother.” They wrote it in there.

JESSIE. Ah, so they put the blame on Auntie Minnie.

DARRELL. They put the blame on Auntie Minnie. For sixty-nine days.

JESSIE. Geez.

DARRELL. It’s in her certificate of death! So, this is back in the sixties, and this is Elk Point hospital. A little bit sketch.

Indigenous Names Change

Indian agents and missionaries put pressure on Indigenous families to follow European naming conventions, and it can be challenging to track Indigenous names through the written record when a researcher is unaware of the oral history. Indigenous family names have shifted over time. We talk about some examples: Piche becoming Wildcat; Petit Couteau becoming Jacknife; Crier becoming Mato; Mahikan becoming Arcan, then Arcand; and a Dion marrying a Buffalo Chip and their descendants becoming known as Dion-Buffalo, then as Buffalo.

JESSIE. And some of them have French names and some of them have Cree names, hey?

DARRELL. Where?

JESSIE. In here.

DARRELL. Oh, that’s Arcands, no?

JESSIE. Yep.

DARRELL. Mosom Alexie?

JESSIE. Arcan, with no d.

DARRELL. [French pronunciation] Arcan, yeah, that’s how they say it in French.

JESSIE. That’s where that name came from?

DARRELL. Arcan, well yeah, that’s . . .

JESSIE. Yeah. So, they have Arcan and then in brackets mahikan. That’s really interesting.

DARRELL. So yeah, so that’s how names change and people—

JESSIE. Even names that you would recognize. Like if someone says “Arcan,” I wouldn’t associate that with Alexander.

DARRELL. You have to figure out. And then they can change. Like last night I was doing some stuff on genealogy about the Wildcats. Except their dad is a Piche. Because that’s, Piche supposedly in French means “wildcat”? And so, they change it to . . .

JESSIE. They changed it to the English?

DARRELL. Yeah, to Wildcat.

JESSIE. And people are changing back to the Cree and stuff now too.

DARRELL. Yeah.

JESSIE. Criers are what?

Darrell. Who?

JESSIE. Criers, some of them are going by Mato now, right?

DARRELL. I don’t know.

JESSIE. I’ve heard that.

DARRELL. But I know like, what the heck is the word? Petit Couteau, Jacknife!

JESSIE. Oh. [laughs]

DARRELL. Small knife! Now they’re Jacknifes.

JESSIE. Do you think they would ever go to like—

DARRELL. Back to? Who knows, who knows? So, you have to know those things. Because I was doing what’s her name’s—I am helping, sometimes I help people. Carol Karakonti’s genealogy. Her mom was a Jacknife, but way back they are Petit, Petit Couteau. They are not Jacknifes. But even like, say, Lawrence, though, Wildcat.

JESSIE. Piches.

DARRELL. No, his brother is a Piche! Same parents, but he’s a Wildcat, so. Victor gave me these sheets; I don’t know where he got those sheets from! But it’s all about that Dion that went to Maskwacîs.

JESSIE. Oh, yeah.

DARRELL. In leg irons. He was a prisoner. He escaped.

JESSIE. And then he escaped to Maskwacîs?

DARRELL. To Maskwacîs.

JESSIE. Where was he a prisoner? Edmonton?

DARRELL. No, Rebellion time. Resistance time.

JESSIE. Oh, it’s that long ago? Wow. The name has been there for a long time.

DARRELL. No, well, no, he changed his name. Because they went—he was a Dion, and then he went there, and then her family was Buffalo Chips.

JESSIE. So then they just went by Buffalo?

DARRELL. They went to Dion-Buffalo, and these kids were all Dion-Buffalos. And then they became Buffalos.

JESSIE. So, they got rid of the Dion and the Buffalo Chips, just went to Buffalo.

DARRELL. Just went to Buffalo, yeah.

JESSIE. So, he just escaped, and he was in leg irons.

DARRELL. When he went and made it to Maskwacîs.

JESSIE. And they just took him in?

DARRELL. And they ended up having eight kids. And so that’s, I think, four sons. Four sons? Five sons? Something like that. I have to look. And that’s where all the Buffalos come from.

JESSIE. There’s so many Buffalos there.

DARRELL. Well, they can trace to all the—

JESSIE. It’s all just to that one Dion.

DARRELL. I think so, unless somebody else was a Buffalo. But I don’t know; I haven’t done much of that. But we connect. But see that’s doing genealogy. We’re not necessarily related to the Buffalos, but we’re related to their relatives. Like Auntie Flo. So, Dion. So, his brother was Auntie Flo’s dad. So, they were related. So, I remember taking Auntie Flo to Maskwacîs to visit her relatives. And one of those—

JESSIE. Her uncle’s—

DARRELL. Yeah, children. So, one of those Buffalo, Dion-Buffalos, was a girl. And who did she marry? Piche, who was Wildcat.

JESSIE. [laughs] So a Dion and a Piche became Buffalo and Wildcat.

DARRELL. Yeah. [laughs] Yeah! There you go. So that’s at Maskwacîs. So then one of them went to Ermineskin and one went to Samson. So, they’re all related, and they’re all related to our relatives and so we’re all . . . the same.

JESSIE. Still connected.

DARRELL. We’re all still connected.

Finding people who changed their name after marriage, ceremony, or another life event can be challenging without the accompanying oral history. For Indigenous individuals, there are rarely authority records tracking an individual’s names.

DARRELL. And people change their names, what they use. Some people go by their second name again.

JESSIE. Totally, yeah.

DARRELL. We know people who go by their first name for fifty years and then change. Now they’re somebody else.

JESSIE. Yeah.

DARRELL. So, what do the records say? Back when they were a kid, they were this? And then as an old lady, they are something else. You have to know some of this stuff.

JESSIE. In libraries, they do a thing where if people change their names, they gather all their names together so people can cross-reference.

DARRELL. Oh, yeah.

JESSIE. It’s called an authority file. So, you can say like, oh, you know this person’s—even a maiden name. If they published books before with their maiden name, and then they got married and so their name is different. Or if they had a pen name, or a nickname that they were known by, and so on.

DARRELL. Oh, yeah.

Correcting Errors

Even our name, Loyer, can appear in the record in multiple ways: Loyer, Loyier, Loyie. In some records, it can also appear as Desnoyer. Errors like these are frustrating for a researcher, but other errors have the potential to harm when a researcher knows the individuals in a record. The metadata that has been assigned to these records betrays not only prejudices of the archivist, but also lacks the specificity that someone from that community could provide. Darrell has had to correct both metadata and display information at the Musée Heritage Museum in St. Albert.

JESSIE. Do you ever see in photos people are misidentified?

DARRELL. Yes!

JESSIE. Oh, yeah!

DARRELL. At the museum in St. Albert! I’ve corrected those at St. Albert. And they want to know. There was one. It was a relative’s wedding. And they had it mis[identified]. It was Millie and Joe’s wedding. They had Auntie Mary, and Joe and Millie, and then they had her parents as . . . I forget. They had a different name for her parents. And I know her parents because the mother of the bride was my grandfather’s sister. So I know them! I knew them as a—like, they were still alive when I knew them!

JESSIE. As real people!

DARRELL. As real people. And they had the wrong names! And I said, “No! I went to this wedding!”

JESSIE. I was there! [laughs]

DARRELL. I was there! And so we ended up correcting it, because I thought it would be really bad and sad if somebody, their relatives or whatever, come in and look at them with the wrong name. And, so—well, Mom works at the museum, so they kind of know me a little bit, so they’re OK to trust me to figure out some of the corrections. Like my mosom, in the picture, there’s a picture of him somewhere and his name is Cayer. C-A-Y-E-R. And it’s just how someone wrote it, and they transcribed it as C-A-Y-E-R instead of L-O-Y-E-R. The o must have looked like an a and the C—

JESSIE. Someone made a loopy L.

DARRELL. A loopy L and now that’s in there. So, we got that changed. But they had it out. And I looked at it and I thought, “Ah, no, there’s a spelling mistake here.” I was a teacher before and I pick up spelling mistakes sometimes, just with my one good eye.

JESSIE. Peeking around! Wasn’t there one too where it was someone and then a neighbour and a whole bunch of kids, but they were not all the same kids from the same family, and someone was like “A Métis Family”?

DARRELL. Oh, Auntie! There was a picture!

JESSIE. Auntie Lizzie, right?

DARRELL. Auntie Lizzie. There’s a picture in the archives; it’s “An Indian Family”!

JESSIE. [laughs]

DARRELL. And there’s a whole bunch of people in there, and it’s like, there are . . . there’s part of one family, and there’s a grandma, and there’s some next-door neighbours, and then there’s some extra kids—cousins—that are in there. And they’re saying this is all one family. It’s like, no! This is, it’s a picture of, well, it could be one family but they’re all—

JESSIE. People who were just over!

DARRELL. They happened to be all there standing at this picture. And so, but that’s how it’s labelled.

JESSIE. “An Indian Family”!

DARRELL. It’s “An Indian Family.” Well, I suppose some of them now would be.

JESSIE. I mean, they’re all related, I guess.

DARRELL. They’re all related. Some of them are. Auntie Lizzie was Métis.

Tracking Race and Ethnicity

There are many inaccuracies in records relating to Indigenous people, but one glaring issue is the way records—live records of birth, for example—tracked race and ethnicity. The entries for these categories varied dramatically for Métis people; white creators of records might have found them hard to categorize.

JESSIE. When they do live records of birth now, do they even have racial origin? Because some of those census categories changed too.

DARRELL. Yeah.

JESSIE. Because back in the day they used to have colour.

DARRELL. Colour: “Red.” Or they put “HB”: Half-breed. Or they put “FB”: French breed. Or, Cree. Or, what else is there?

JESSIE. So, they would say what kind of Indian you were?

DARRELL. Sometimes.

JESSIE. Or would they just say “Red”? I guess it depends who was taking the census, right?

DARRELL. Yeah, sometimes just “Red,” “R.”

JESSIE. I’ve seen that before.

DARRELL. But that, depending on what the questions were too, and what language they talked, some of them just put “Indian.”

JESSIE. They talked “Indian”? [laughs]

DARRELL. They talked “Indian.” Yeah, right.

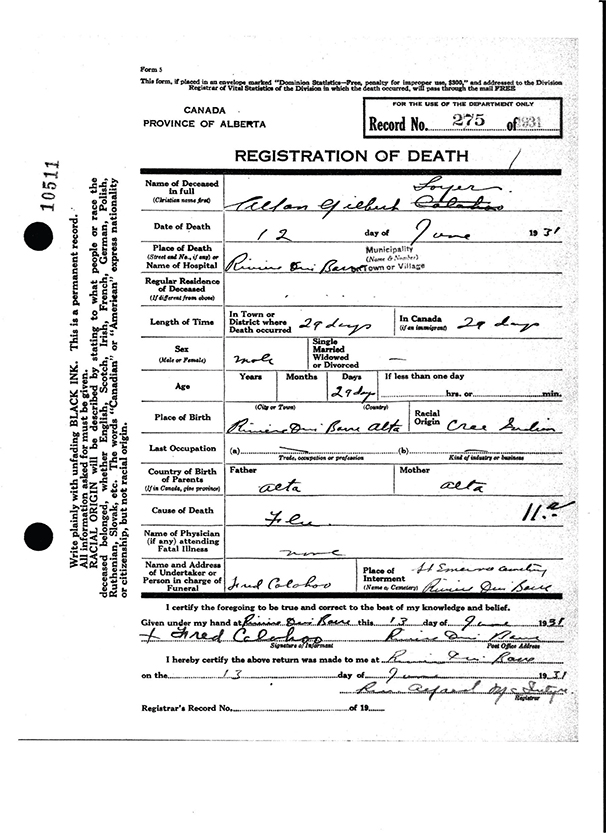

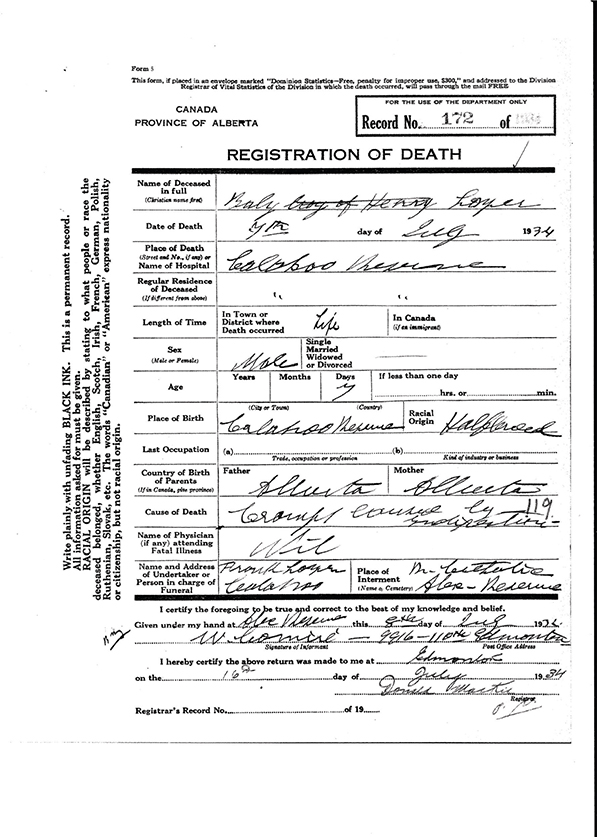

In one case, Darrell found the death records of two of his uncles who passed away in childhood. Though they had the same parents—Henry and Clara Loyer, who were both Métis people—these two brothers are listed as having two different “racial origins”: one baby is listed as a “Cree Indian” (Figure 2) and the other as a “Half-breed” (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Photocopy of the death certificate of one of Darrell’s uncles, Allan Gilbert Loyer, which lists his “racial origin” as “Cree Indian.” Provincial Archives of Alberta. Death Records, Loyer, Allan Gilbert, Record no. 275 of 1931.

Figure 3: Photocopy of the death certificate of one of Darrell’s uncles, whose name is recorded as “Baby boy of Henry Loyer” and whose “racial origin” is listed as “Half-breed.” Provincial Archives of Alberta. Death Records, Loyer, Baby Boy of Henry, Record no. 172 of 1934.

DARRELL. “Baby boy of Henry Loyer.” “Seven days.”

JESSIE. Seven, that’s so—

DARRELL. “Racial Origin: Half-breed.”

JESSIE. So, his brother was a “Cree Indian”—

DARRELL. His brother is a “Cree Indian,” and this one is a “Half-breed.” Same parents.

JESSIE. Oh my God, ridiculous.

DARRELL. And he’s buried, this one is buried at Alexander, and this one is buried at RiviËre Qui Barre. So, the “Cree Indian” is in Qui Barre, and the “Half-breed” is on the reserve.

JESSIE. [laughs]

DARRELL. Go figure.

Even Darrell’s own birth information had a strange error.

DARRELL. People who filled out forms made assumptions. And so, on my form, I’m “French.”

JESSIE. [laughs] On your birth certificate?

DARRELL. Not on my birth certificate, on my registration of live birth. Because I was just curious, and so that’s something you can get from just a registry. So, I went when I had to do my license. I thought, “I’m going to go see if they have that.” You have to pay for it. So, I got it and it’s my registration of live birth, and it says what hospital, etc. And, yeah, my mom is “French.”

JESSIE. [laughs]

DARRELL. And she signed!

JESSIE. She was like, “Yes, I’m French!” I mean, Savard is—

DARRELL. No, she was Loyer.

JESSIE. Oh, she was Loyer, yeah. [French pronunciation] Loyer! She said she was French, that’s so funny.

DARRELL. Well, they filled it out and she signed it. I don’t know if she read it. Lots of times—

JESSIE. I wonder if they would have put “Half-breed.”

DARRELL. They did on some people’s forms. Lots of the old census—

JESSIE. I wonder if any of your sisters are half-breeds on their registration of live birth.

DARRELL. I have no idea.

Métis Naming

While it is not necessarily an inaccuracy, a quirk of Métis family life could be a possible obstacle in tracing someone’s genealogy: Darrell spoke about the way that Métis families might have multiple instances of the same name. If a child died, and the parents renamed their next baby with that same name, a genealogy listing might have several kids in the same family with the same name. Names often stayed in families too: boys named after their dad might name their children after their father, so three generations might share that name, with the name showing up multiple times in the same generation. Darrell has found an example of that: his grandfather was named Henry Loyer, but there is another Henry Loyer around the same age who was his first cousin.

DARRELL. Oh, this is another Henry. I saw the records all the time: Henry Loyer, Henry Loyer, right? And I thought, “My mosom was old when he got married. I wonder if he got married twice?”

JESSIE. Oh, no?

DARRELL. He didn’t. It was somebody else. It was another Henry Loyer. So, I found this other Henry Loyer.

JESSIE. Do you know how he’s connected?

DARRELL. Oh, now! He was . . . I think he comes from Cyprien, Cyprien’s kid.

JESSIE. So that’s Elzear’s brother?

DARRELL. Elzear’s brother’s kid. So, they, two brothers, both named their kids Henry.

JESSIE. Oh, my God.

DARRELL. So, yeah, it causes a little bit of . . .

JESSIE. Especially since they’d be around the same age!

DARRELL. Oh, yeah, they would be. His father is Henry William Loyer. And our Henry is Henry . . . I don’t know if he’s got a second name.

Later, he corrects himself when he shows Henry William Loyer’s marriage certificate to Jessie.

DARRELL. And this is my mosom—oh no, this is the other Henry. This one was really . . .

JESSIE. His cousin.

DARRELL. His cousin. At Burtonsville. Born in St. Albert. Oh no, his wasn’t—remember I said Cyprien? No, it’s not Cyprien; it’s Samuel.

Jessie. Oh.

DARRELL. Elzear’s other brother is Samuel.

Where Are the Women?

Patriarchal ideas about ownership and identity obscure many women’s lives in the historical record. For example, in Figure 3, one of Darrell’s uncles, who passed away as a baby, is referred to on his death certificate as “Baby boy of Henry Loyer”; his mother, Nanny (Clara Loyer, née Cunningham), is not mentioned anywhere on the document. Another example is of Darrell’s great-grandmother Josephine Laderoute, who was married twice, first to his great-grandfather Elzear Loyer and then to a man from Alexander that they called Mosom Alexie. On her second marriage certificate, Josephine signs her name in a surprising way.

DARRELL. Then after he dies, she marries Mosom Alexie from Alexander. Alexis Arcand. He was fifty-nine and she was sixty-two.

JESSIE. Oh!

DARRELL. She was a widow. And she signs her name, the poor thing: “Mrs. E. Loyer.”

JESSIE. She signs after her dead husband. On her second marriage.

DARRELL. On her second marriage. That’s here. That’s the records.

JESSIE. Such a wild way to track women.

DARRELL. Yeah. She signs “Mrs. E. Loyer.”

JESSIE. Well, what was her maiden name?

DARRELL. Laderoute.

JESSIE. What was her first name?

DARRELL. Josephine.

JESSIE. Yeah, but none of that is in there.

DARRELL. None of that is. And she signs as a sixty-two-year-old. She could write her name, but pretty sketch, pretty scriggly.

In addition, on Nanny’s marriage certificate, they do not list her mother’s place of birth; only her father’s place of birth is noted. Her mother’s place of birth is not listed, and only her first name appears.

DARRELL. “Name of mother:” just Josephine. Not where she’s born, just her. So sad.

But records can also show women asserting their identities. One example is from Jessie’s great-grandmother, who made an additional note on her marriage certificate to let people know she was literate.

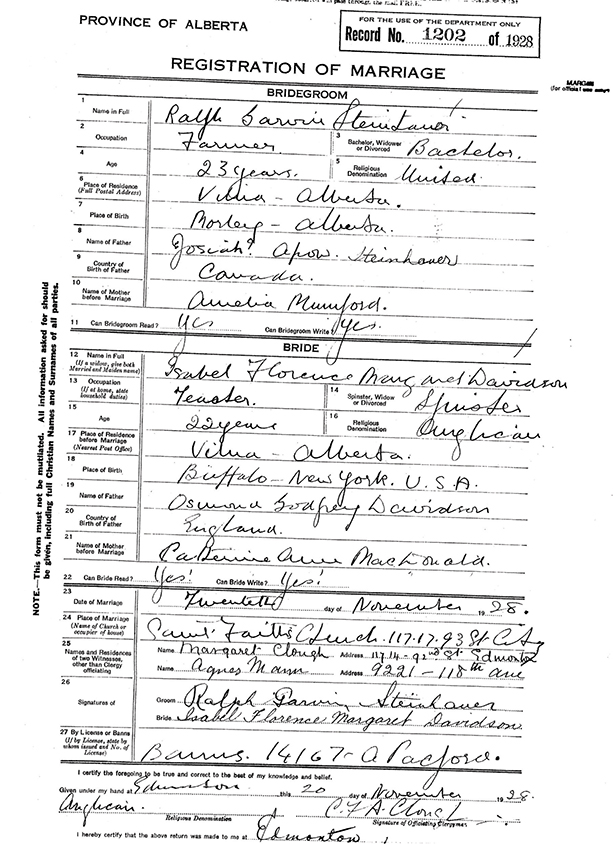

DARRELL. Then I got Mom’s grandparents, so Ralph Steinhauer and Isobel Davidson (Figure 4). It’s funny! ’Cause they ask questions.

Figure 4: Photocopy of marriage certificate of Ralph Steinhauer and Isobel Davidson, Jessie’s great-grandparents. Isobel, in response to questions about her ability to read and write, wrote “Yes!” with an exclamation mark. Provincial Archives of Alberta. Marriage Records, Davidson, Isobel, Record no. 1202 of 1928.JESSIE. Like what?

DARRELL. “Can the bride read?”

JESSIE. Oh.

DARRELL. She was a teacher!

JESSIE. Yeah, so yes.

DARRELL. “Yes!” with an exclamation mark. “Can bride write?” “Yes!” with an exclamation mark.

JESSIE. [laughs] Some attitude there.

DARRELL. Some attitude. So, she filled this out. Or somebody filled it out. Because it was like, “Yes!” with an exclamation mark. Like why? Grandfather, Mom’s grandfather—

JESSIE. Does it ask if the groom?

DARRELL. “Can the bridegroom read?” “Yes.” “Can he write?” “Yes.” But no exclamation, just for her.

JESSIE. She wanted to make sure!

DARRELL. She wanted to make sure.

Replicating Inaccuracies

There are many inaccuracies in genealogies of Indigenous people. When people are not aware of the oral history of families and rely solely on written family trees, these inaccuracies can be replicated as they move online.

DARRELL. I heard she bought some genealogy. And so then she was looking through it, and it didn’t look right for some reason. So, she brought it to me; she made a photocopy. And I’m in there, but I’m married to Mom, to the same wife, I have the same birthday, but not to the same family!

JESSIE. You’re from a different family?

DARRELL. From a different family. There’s other—people think a Darrell Loyer or some name, and they just plop it into the tree. They think that’s what it is.

JESSIE. And they just run with it.

DARRELL. They run with it. And once it’s printed, that’s the hard part. Once it is printed in somebody’s genealogy or printed in a book or printed somewhere, then everybody thinks it’s true. So, you’ve got to watch, you’ve got to be careful.

Many genealogy records exist on the basis of multiple assumptions about, for instance, ages of married couples or nicknames being used as full given names.

DARRELL. The person doing the genealogy there made some really . . . some of the genealogy in St. Albert, in that system—and you can’t change it now because it’s hers—is not good.

JESSIE. Oh, really?

DARRELL. No. She’s got some people who are married to their mothers.

JESSIE. Ew.

DARRELL. Yeah. Because they have the names and it’s just—

JESSIE. They just thought it was the same person.

DARRELL. They just thought somebody was the same person. Sometimes they don’t think that somebody who is thirty-five could marry somebody who is seventeen. They think that maybe is their daughter or something else. Or older, you know?

JESSIE. So then, all that stuff is now in the archives as, like, truth.

DARRELL. Well—

JESSIE. As facts.

DARRELL. I guess so, but then you have to, you’ve got to weed through it.

JESSIE. Have you fixed stuff for them?

DARRELL. Well, no, because they won’t let you. Because it’s that person’s stuff. But they do, they say that they know that there are mistakes; they say that. So, they advise people to do some of their own research. Some of it is good. Lots of it is good. And also, there is stuff in there that you know that it was done not . . . how should I put this?

JESSIE. [laughs]

DARRELL. It was done, just by asking somebody? Like, for instance, they said—if you look at my mom, what are her kids’ names?

JESSIE. [laughs]

DARRELL. They are in there, and one of the kids is Gina, listed as Gina. That’s not her name! That’s her nickname. And so that is in there as a record that she has a daughter named Gina. She has a child that has a nickname named Gina, but not that. So that is confusing.

JESSIE. Confusing for people who don’t know.

DARRELL. People who don’t know. If they would search for a record for Gina, they would never find her later on. Her baptism doesn’t say Gina, her birth doesn’t say Gina. That’s her nickname. But that record in St. Albert has her as Gina, that’s her name. So, I always think, if that’s the situation for that family . . .

JESSIE. For just ours.

DARRELL. So other people? You always wonder if it’s right or not. So cross-referencing and double-checking and on and on and on.

Some types of records are more trustworthy than others; obituaries, in particular, are not the most accurate source.

DARRELL. One thing is a problem that—I think that St. Albert had—was she used the obituaries.

JESSIE. Oh, very glowing.

DARRELL. Don’t use the obituaries, 100 percent. Use them sort of. But not . . . use them to sort of help you get at sort of an idea, because people might say their sister is so-and-so and so-and-so and so-and-so and really, they are not. They have a sister relationship to them. But they are in their obituary.

JESSIE. Well, and it’s always political who gets into the obit.

DARRELL. Well—

JESSIE. Like how many kids?

DARRELL. Sometimes.

JESSIE. Whose wife?

DARRELL. Yeah.

JESSIE. If somebody got married but they’re no longer together, do they make it in?

DARRELL. Yeah.

JESSIE. If they’re on the rocks, do they make it in? [laughs]

DARRELL. Yeah, no, so it’s really, but I think that was put in—I think some of the genealogy that people do like that is . . .

JESSIE. A little sketch?

DARRELL. A little sketch. But some of it is good! But you have to weed it through.

Part 3: Considering the Future

What Is an Indigenous Archive?

We thought that an Indigenous archive could be many things, including the people who hold these stories, like elders, and possibly beadwork and other items that hold stories too.

DARRELL. What’s an Indigenous archive? I think two things, maybe.

JESSIE. [laughs] Two points.

DARRELL. [laughs] Two points. No. Indigenous archives might be an elder. ’Cause they’re just—but it’s not written, it’s in their head. Or if it’s written, it’s squirrelled away somewhere. When I die, you guys will find stuff written all over.

JESSIE. Oh my God, I know.

DARRELL. [laughs]

JESSIE. Excavate this house.

DARRELL. No, yeah, like little gems of stuff. Like, I found one of Nanny’s, a little diary the other day, just about one little notepad with only about a month. A month, I think, when Tony was born. There’s all kinds of stuff. I didn’t throw any of the genealogy away that I did on paper. I just transferred it into computer, so all that’s around the house somewhere in boxes.

JESSIE. Do you think there are other things that are archives too, like people’s beadwork and stuff?

DARRELL. Or is that museum?

JESSIE. Well, it could be a museum.

DARRELL. Mom told me: oh, I got schooled!

JESSIE. Why?

DARRELL. Between the difference between archives and museums.

JESSIE. What is the difference, according to Mom? [laughs]

DARRELL. Archives, wait . . . museums are objects. And archives are, like, pictures and paper and stuff. I think. Anyway, so archives could be run by—Indigenous archives could be run by Indigenous people. That might make sense.

JESSIE. Could be. Well, you were even saying that at the provincial archives there’s a different section. Where they did things differently. Like, what did they do differently?

DARRELL. Oh, they’ve got stuff in circle, and they’ve got . . . I don’t know, it has a different feel to it; it’s good.

JESSIE. Yeah? What do you like about it?

DARRELL. I don’t know. It tells people’s story.

JESSIE. Yeah. Do you think it’s more accessible or is it . . . it just, like, feels better?

DARRELL. It just is.

JESSIE. Just different.

DARRELL. Yeah.

JESSIE. Yeah, there’s less sort of distinction, I think, between libraries, archives, and museums for Native people.

DARRELL. Probably. It’s all—

JESSIE. ’Cause it’s all tied together.

DARRELL. It’s all stuff.

JESSIE. It all has stories attached to it.

Simply having Indigenous people working in archives can address some of the obstacles facing Indigenous researchers. At the PAA, Darrell was helped by a staff member who shared relatives with us.

JESSIE. Is that the person that we’re related to, that works there?

DARRELL. No, we share relatives.

JESSIE. Oh, OK.

DARRELL. But she was good. Once we found out, then she would bring me stuff. She works in the back, finding stuff. ’Cause she started looking at the stuff, my requests, then when she come bringing me them, she said something about, “I think we’re related.”

JESSIE. She was like, “And these are my people too.”

DARRELL. No, she said, “Yeah, I think we’re related to these same people.” She was very helpful. And then after I did a whole bunch of that kind of genealogy, then she started showing me other stuff, so I had, like, an in . . . so she was good. So, then she showed me, oh, stuff I’d already seen before, like the Louis Kwarakwante stuff, those big maps and that. And then she showed me, the last time I went, she showed me pictures.

Sometimes local history books, created by communities, can provide an alternative to dominant narratives perpetuated by non-Indigenous people creating records about Indigenous people.

DARRELL. Oh, what’s her name does good work, that Gail Morin’s books and stuff. She puts out lots of good genealogy.

JESSIE. What about all those local history books, you know, like where they have “Calahoo Trails” or whatever?

DARRELL. Oh, yeah! [laughs] You’ve got to be careful with them. Because sometimes they’re written . . . depending on who the authors were. Sometimes they are very, uh, very white. And so, the Indians were there only at the beginning and then gone, even though they still live right next door to where they live!

JESSIE. [laughs]

DARRELL. But some of them are really good, and they talk about families. There’s one at Elk Point is good. Talks about Kehewin and Moose Mountain people and stuff. That’s good. But it was written by educated Aboriginal folk. The articles. You can tell, because they say who wrote them. So that part is kind of good. I read some of those, they’re good. You can get good genealogy from stuff like that.

JESSIE. Yeah, I guess.

Records Providing Clarification

The records, despite having inaccuracies, have also provided clarification. Some stories were not shared in families, especially around babies’ deaths. Other times, people were known only by a nickname. Darrell shares the story of using genealogical records to find out why his mosom’s grandfather had a particular nickname.

DARRELL. But part of it was also for clarification because, for instance, Nanny . . . some of it was just oral history stuff, like Nanny’s husband, my mosom’s grandfather, they only knew him by his nickname. Livershawn.

JESSIE. Livershawn?

DARRELL. Livershawn! But that’s what we used to say, “Livershawn.” But once I looked at stuff and did some research, it was “Divertissant.”

JESSIE. Oh. [laughs]

DARRELL. But it was Livershawn.

JESSIE. Livershawn!

DARRELL. So, what was his name? His name was “Livershawn,” and we would think, “OK, that’s a weird name.”

JESSIE. That’s a wild name!

DARRELL. That’s a wild name. And then, in actuality, and then his dad was only named Bonhomme.

JESSIE. Oh, yeah.

DARRELL. But their actual both names were Louis. So, all the records have them as Louis. So, then, that clarified that.

Visiting for Stories

Nanny, whose knowledge could have filled a library, is someone we know and remember through stories, but we also learn about her through records. She was connected to a network of other knowledgeable people and shared stories with them through visiting.

JESSIE. Do you remember anybody that was super knowledgeable when you were a kid? About all kinds of stuff? I mean, Nanny.

DARRELL. Everybody. Everybody old. Anybody.

JESSIE. Who do you remember?

DARRELL. Oh, what the hell was that old lady’s name? She had no hair.

JESSIE. She had no hair? [laughs] At all?

DARRELL. No! She lived by Gunn. We’d go visit her. She had a cat that would catch rabbits.

JESSIE. Oh, my God. Pretty sweet.

DARRELL. No, her cat caught her rabbits. Because I remember! And she’d take out her window in her kitchen. Old windows you could take out, and in the summer she’d take [it] out, and the cat jumped through the window carrying a rabbit! I was a kid, and it was a big memory! Holy shit!

JESSIE. [laughs]

DARRELL. [whispers] Oh, I shouldn’t say that. [laughs]. No, and this rabbit—

JESSIE. Was she scary, kind of? No hair . . .

DARRELL. She was kind of scary, but as a kid. She was old, she was one of Nanny’s friends, cronies. And we went there. She must have been older than Nanny, because we went there to visit. I’m trying to remember who she was. I’m going to have to ask Tew.

JESSIE. She had a lot of stories? She knew a lot?

DARRELL. Oh, yeah. She knew lots. Lots. But yeah, the one thing I remember, she had this cat that killed a rabbit. That would bring her, that was her—

JESSIE. Her hunter.

DARRELL. Her hunter. She was an old lady.

JESSIE. I guess, yeah. I wonder if she taught that cat to do that, or if she just had a good cat.

DARRELL. I have no idea.

Records Will Never Tell the Whole Story

As people reconnect to their genealogy, it might be enticing to dive into the archives for evidence of their ancestry.

JESSIE. Is there lots of that too, where they don’t say if people are half-breeds or not? Or is that pretty clear?

DARRELL. No, it’s clear. Well, I don’t know.

JESSIE. Because people always talk now, where they say, “Oh, my granny hid it,” or whatever.

DARRELL. We never had that choice. I guess people did, hid it, but . . .

JESSIE. Did you know of anybody that, like, pretended to be white?

DARRELL. Some of them are big Métis now! But I suppose it’s good if people find out who they are. But I don’t know.

JESSIE. Do you think with people knowing genealogy, people actually did know who was Métis and who wasn’t?

DARRELL. Oh, yeah, people know who people are. You have to find out certain names. And then people, I always ask people. They say a name, and I say, “No, what’s a real name?” Like, even though they say, “That’s my real name!” No, what’s your connected name to the community?

JESSIE. Well, you were even saying that person that Mom said she knew, or we had a mutual friend, and I was like, “Well, he’s a L’hirondelle.”

DARRELL. Yeah, so you have to go back to a name that is recognizable as a Métis or a First Nation name. ’Cause otherwise, you kind of wonder who they are.

JESSIE. Because people have different kinds of names now.

DARRELL. Oh, everybody! Like lots of different names. Before everybody was just all named the same, so it was easy. A Letendre married a L’hirondelle married a, I don’t know, married a Loyer married a Cunningham, married this, married that, so it was like, OK! They all knew each other! Belcourt! Bellrose! We all knew each other, and so it was easy.

There is a sense of urgency around passing on cultural knowledge, as elders who hold this knowledge pass away, especially since visiting—sitting with the old people, listening—is the primary way that Métis cultural knowledge continues to be passed on. Darrell spoke about the way that Judy Iseke’s elders series uniquely shows that kind of knowledge transmission through visiting (Iseke 2020) and reflected on the kinds of questions he would have asked the old people in his life before they passed away.

JESSIE. Is there anything that you wish you’d asked people about?

DARRELL. Oh, Jessie. Yeah. I wish I would have written down more. I did some, back when Nanny was still alive; that’s why I started. Because it was in my head but then I thought, when I got serious about “I need to do a paper or whatever” about some of it. Then I wrote some stuff down. And I look back at some of that old stuff, and it’s scary. I saw Livershawn in there, like “Livershawn” Loyer.

JESSIE. “Livershawn Loyer.”

DARRELL. “Livershawn Loyer.” Divertissant! But actually his name was Louis! But I would have asked way more stuff. I’d have asked stuff now about Spanish Flu.

JESSIE. Oh, yeah.

DARRELL. Only because of this COVID. Because they lived through the first go-round. Because she would have been eighteen. 1918: Nanny would have been eighteen, nineteen.

JESSIE. She was young.

DARRELL. She was young, she’d have known.

JESSIE. She would remember.

DARRELL. She would remember. I would ask more about . . . more stuff about people dying. What did they die of? When did they die? If they knew, like . . . people didn’t talk. People didn’t ask questions. Kids didn’t ask questions. If they told you stuff, they told you. And you knew about certain things. But no, I’d ask now way more stuff.

JESSIE. Yeah.

DARRELL. I’d ask about different stuff, about herbs and stuff too.

JESSIE. Oh yeah, all her midwife—

DARRELL. All her midwifery stuff. I didn’t ask.

JESSIE. ’Cause, like, when you were growing up, all that stuff was around, but you were a little kid?

DARRELL. Yeah, well, I was. She was still doing it when she was old. So, I was in my—well, she died when I was twenty-three. So, think about twenty-three—like, I give myself credit I got some genealogy written down and I had it in my head, up to twenty-three, but . . . you’re kind of not thinking about asking old stuff. Oh, yeah, I wish I could just pick up the phone and phone her now and just ask about this or that, but no. Oh, lots of things to ask about, yeah. But people don’t. They don’t think. They’re young.

JESSIE. You don’t realize until later.

DARRELL. Until you’re old and they’re gone.

Conclusion: Remembering Everyday Lives

Both of us realize that records from libraries, archives, and museums will never tell the whole story: they can fill in gaps, clarify, and confirm. Some stories will never show up in the record: sacred stories, told at certain times, in the right context. But there are other stories that are precious for how they connect us to the small, everyday lives of our ancestors, like the way that, as a midwife, Nanny was known to kiss babies after she delivered them.

JESSIE. Do you know how she started doing the midwife stuff?

DARRELL. No clue.

JESSIE. Just had a bunch of kids?

DARRELL. I guess so, I don’t know. I have no idea. Zero. But I know she delivered a whole crapload of folks around here. Like Harold Granger is one of them. ’Cause that’s what he teases Audrey about. Nanny was the first woman that kissed him. ’Cause that was, I guess, her trademark. She’d deliver a baby and then kiss it. And so, then they would talk about that later and stuff; people talk about that. And so, he teases his wife.

JESSIE. His first kiss?

DARRELL. His first kiss was from Mrs. Loyer.

JESSIE. [laughs]

Métis genealogy is often held in small, everyday stories like this one about Nanny. As more people turn to archival sources and genealogy companies to map their kinship, we’re grateful for kitchen table talks that allow us to share these oral histories in the way that they were transmitted: over tea, with family, as funny little stories.

Acknowledgements

There are many cultural memory institutions noted in our conversation: St. Albert Musée Heritage Museum, the Provincial Archives of Alberta, the Hudson’s Bay Archives, the Glenbow Museum. Many of these stories and family histories came from Clara Loyer (Nanny), née Cunningham. Chris Tse edited the condensed audio files.

References

Alberta on Record. n.d. “Fonds glen-824 - Charles Denney Fonds and Métis Genealogy Files.” Accessed July 1, 2020. https://albertaonrecord.ca/charles-denney-fonds-and-metis-genealogy-files?sf_culture=en. Archived at: https://perma.cc/3QVN-NDMV.

Carlson, Nellie, Kathleen Steinhauer, and Linda Goyette. 2013. Disinherited Generations: Our Struggle to Reclaim Treaty Rights for First Nations Women and Their Descendants. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press.

Iseke, Judy. 2020. Our Elder Stories. Accessed July 1, 2020. https://ourelderstories.com/. Archived at: https://perma.cc/CU5M-QQU7.

Israel, Robin H., and Jodi Reeves Eyre. 2017. “The 2017 WArS/SAA Salary Survey: Initial Results and Analysis.” Women Archivists Section. Society of American Archivists. https://www2.archivists.org/sites/all/files/WArS-SAA-Salary-Survey-Report.pdf. Archived at: https://perma.cc/X8X8-VZ5R.

Mattes, Cathy, and Sherri Farrell Racette. 2016. “Curating as Kitchen Table Talk.” Curator talk, July 21, 2016, Plug In ICA, Winnipeg, MB, 1:05:31. https://plugin.org/curating-as-kitchen-table-talk-curator-talk-with-cathy-mattes-july-21-2016/. Archived at: https://perma.cc/U7QT-4NPC.

Provincial Archives of Alberta. 2019. “Meet Darrell.” Facebook. October 5, 2019. https://www.facebook.com/www.provincialarchivesofalberta/photos/a.315952045231888/1336216086538807. Archived at: https://perma.cc/2D3J-UA9F.

Footnotes

1 For a good example of kitchen table talks as research methodology, see Nellie Carlson, Kathleen Steinhauer, and Linda Goyette, Disinherited Generations: Our Struggle to Reclaim Treaty Rights for First Nations Women and Their Descendants (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2013).

2 Upon review, Darrell realized he misspoke; the cousin he had talked about was Hazel, Irene’s sister.